Art & Exhibitions

More Than 30 Works by Edvard Munch Are Missing From Oslo. Did University Students Steal Them?

Works by the famed painter and five other artists disappeared after a loan scheme to a student housing complex.

Works by the famed painter and five other artists disappeared after a loan scheme to a student housing complex.

Javier Pes

The Munch Museum will be sending nearly 50 prints to the British Museum in London in April for the UK’s biggest exhibition of the Norwegian artist’s celebrated works on paper for almost 50 years. But the epic loan will not include 34 works by the artist that have gone missing—and are suspected stolen. The Oslo museum is hoping to track down the works, which disappeared decades ago.

The theft of a trove of art by Norway’s most famous artist has gone largely unreported: there was no dramatic heist to capture international headlines. Instead, many of the prints are believed to have been pilfered by students from the halls of dorms, where they were until the 1970s as part of a remarkable, if risky, loan scheme.

An investigation by the Norwegian newspaper Dagladet has revealed that 34 Munch prints that should be part of the Munch Museum’s collection are, in fact, missing. All of them come from a trove of works donated to the city of Oslo by a Norwegian businessman, Rolf Stenersen (1899–1974) in 1936. Around 15 years later, because the works had not gotten a dedicated home, the city and Stenersen agreed to display them on the walls of a student housing complex. Until the 1970s, valuable works by Munch and several of his contemporaries hung at the Sogn Student Village in the dorm rooms, hallways, the canteen, and other communal areas.

But a few of the students abused his generosity, walking off with the works. The theft of Munch’s painting, History (1911–60), from the student restaurant in 1973 helped put an end the loan arrangement. After theft, the canvas was quickly recovered—but 47 works by Munch, Erik Harry Johannessen, Jakob Weidemann, Ludvig Karsten, Rolf Nesch, and Kai Fjell are still at large.

Edvard Munch’s History (1911-16) was soon recovered but many other works missing from the student village have never been seen again. Courtesy of Munchmuseet.

The Stenersen collection was transferred from Oslo’s municipal collection to the city’s Munch Museum in 2010, by which time the trail for many of the missing works had gone cold. Munch’s descendant Elisabeth Munch-Ellingsen has called the situation “truly scandalous” and hopes that former students might be able to shed light on the missing works. Meanwhile, the Munch Museum’s director, Stein Olav Henrichsen, said that it has not had the resources to search for the prints. He agreed that the care of the collection at Sogn left much to be desired and hopes that anyone with knowledge of the works’ whereabouts will come forward.

Dagladet, which began digging into the Munch archives a year ago, has revealed how some of the works went missing in the first place. In 1967, records of Sogn’s Student Society noted that Munch’s Crying Woman by the Bed was cut out of its frame and “replaced with a Picasso reproduction.” Other stolen works include Munch’s The Girls on the Bridge, Drawing, and Kiss

Stenersen, the collector who donated the prints, didn’t make it particularly easy for registrars to keep track of the works. His grandson, Sven Stenersen, told Dagladet that the collector caused confusion by adding and removing work from the gift at will and leaving no records of his decisions. He would simply tell the caretaker, “Here is a new addition to the gift,” or “I don’t want this anymore.”

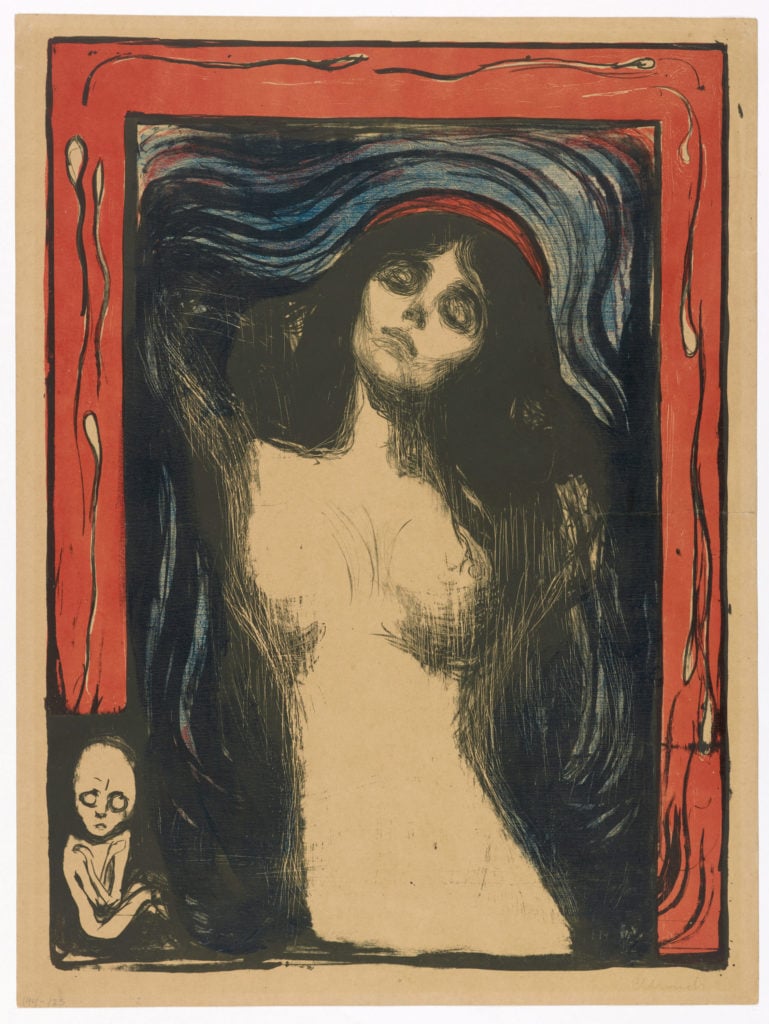

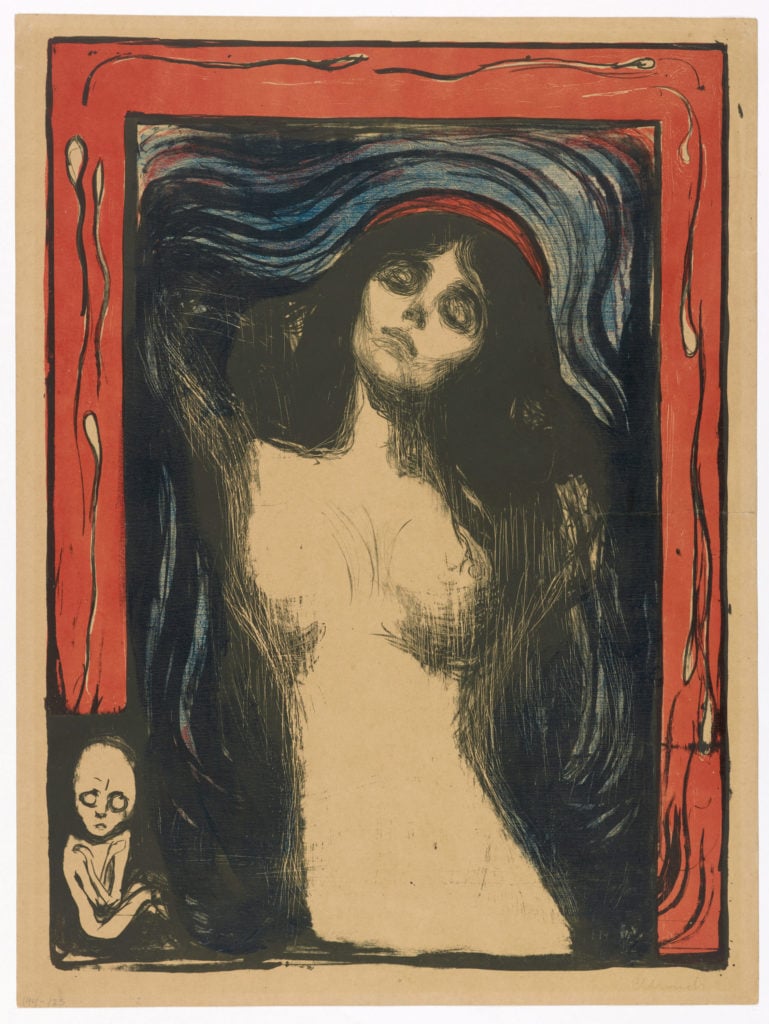

Record-keeping will be meticulous for the Munch Museum’s loans to the British Museum for “Edvard Munch: Love and Angst,” which is due to include 83 works drawn from both museums’ collections and other lenders. Star works will include Munch’s Vampire II as well as Madonna, an erotic image that caused outrage (it features swimming sperm and a fetus). A print of his most famous work, The Scream, is being lent by a Norwegian collector.

In a statement, the exhibition’s curator Giulia Bartrum said: “This exhibition will put Munch into context within the Old Master tradition and look at the remarkable impact of his prints alongside other leading printmakers of his period.”

The British Museum’s Munch show is sponsored by the London-based company AKO Capital, founded by the Norwegian billionaire collector and philanthropist Nicolai Tangen. Unlike Stenersen, the fund manager is leaving nothing to chance. He has placed his 1,000-strong and growing collection of Modern Nordic art in a foundation to be housed in the Kunstsilo, a 100 million Norwegian Krone ($11.6 million) museum being built in the city of Kristiansand.

Meanwhile, the Munch Museum is due to move to a landmark building designed by the Spanish architects Estudio Herreros on the Oslo waterfront in June 2020. It is also digitizing the museum’s 28,000-strong collection, including Stenersen’s gift.

“Edvard Munch: Love and Angst,” runs from April 11 through July 31 at the British Museum in London.