On View

The Poet e.e. cummings Was Also a Painter, and His ‘Radical, Abstract’ Work Is on View at the Whitney

The poet-painter's work is on view as part of the show "At the Dawn of a New Age."

The poet-painter's work is on view as part of the show "At the Dawn of a New Age."

Vittoria Benzine

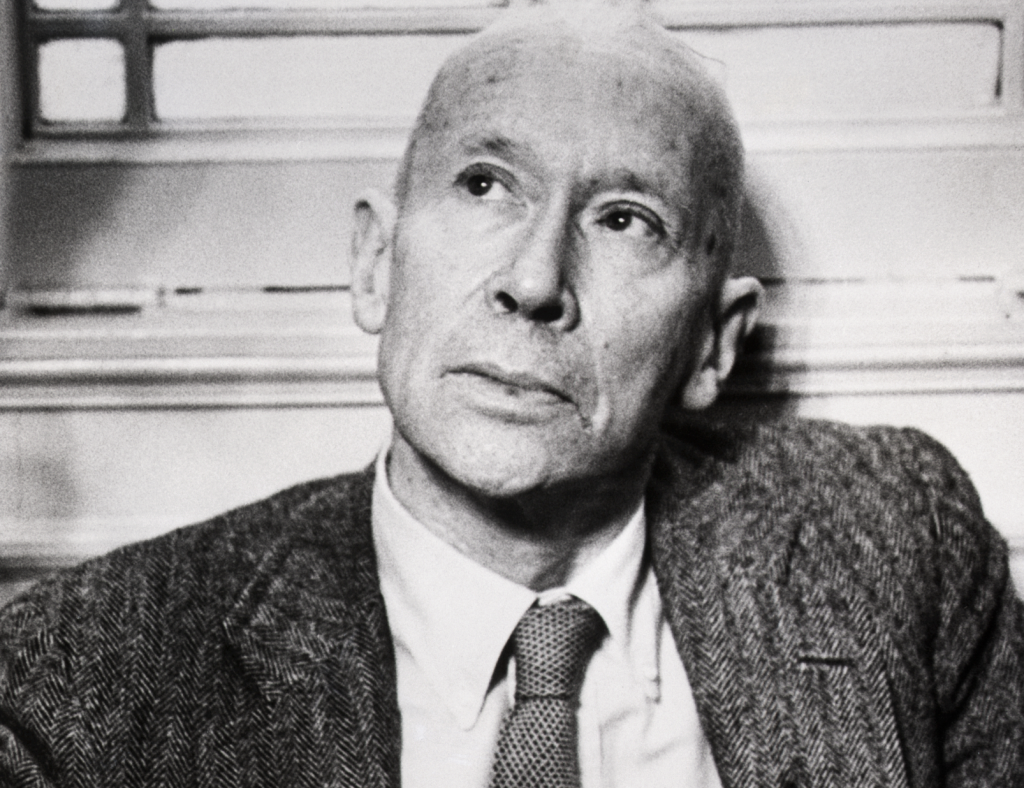

The poet e.e. cummings, a rare household name who brought avant-garde syntax (and head-turning lowercase usage) to the everyday reader, composed at least one poem per day between the ages of 8 and 22.

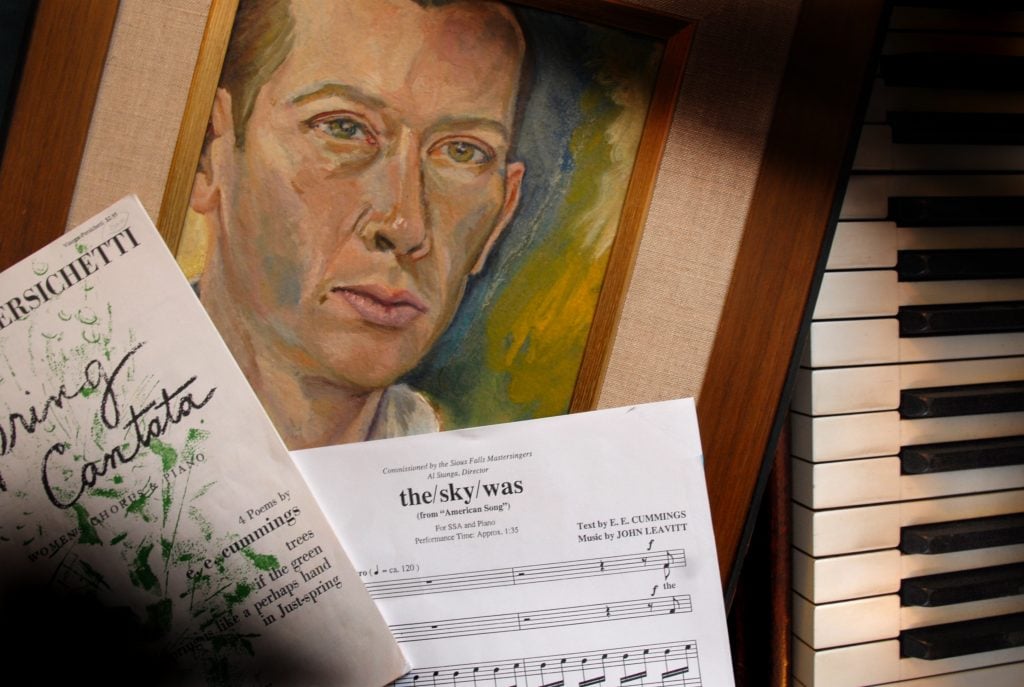

“At the Dawn of a New Age,” an exhibition at the Whitney Museum that explores oft-forgotten American modernists active from 1900 through the 1930s, re-asserts cummings as an equally disciplined painter—and a cutting-edge one at that.

The show, which is on view until February 26, 2023, takes its title from a quote by the literary critic Van Wyck Brooks. “America is living at the dawn of a new age of humanity,” curator Barbara Haskell paraphrased for Artnet News. She curated the show specifically to introduce viewers to the forthcoming Whitney Biennial to deep cuts from the museum’s permanent collection.

Installation view of “At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism.” Front left: e. e. cummings, ‘Noise Number 13,’ 1925. Photograph by Ron Amstutz. All photos courtesy of the Whitney Museum.

Assembling the show, however, challenged Haskell’s own preconceived notions about art history. “We think of early modernism as being a handful of artists,” she said, “but in fact there was this wide swath of artists who were channeling the developments of Cubism and Fauvism and turning it into a native-born American modernism.”

“That was the thrust of the show,” Haskell continued, “to break open the canon.”

The Whitney has helped create that canon, in fact. As a press release for the show notes, the Whitney widely ignored works from early American modernists until the mid-1970s, since the museum’s loyalty then lied with “the urban realists who formed the core of the Whitney Studio Club,” a social organization for artists founded by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney in 1918.

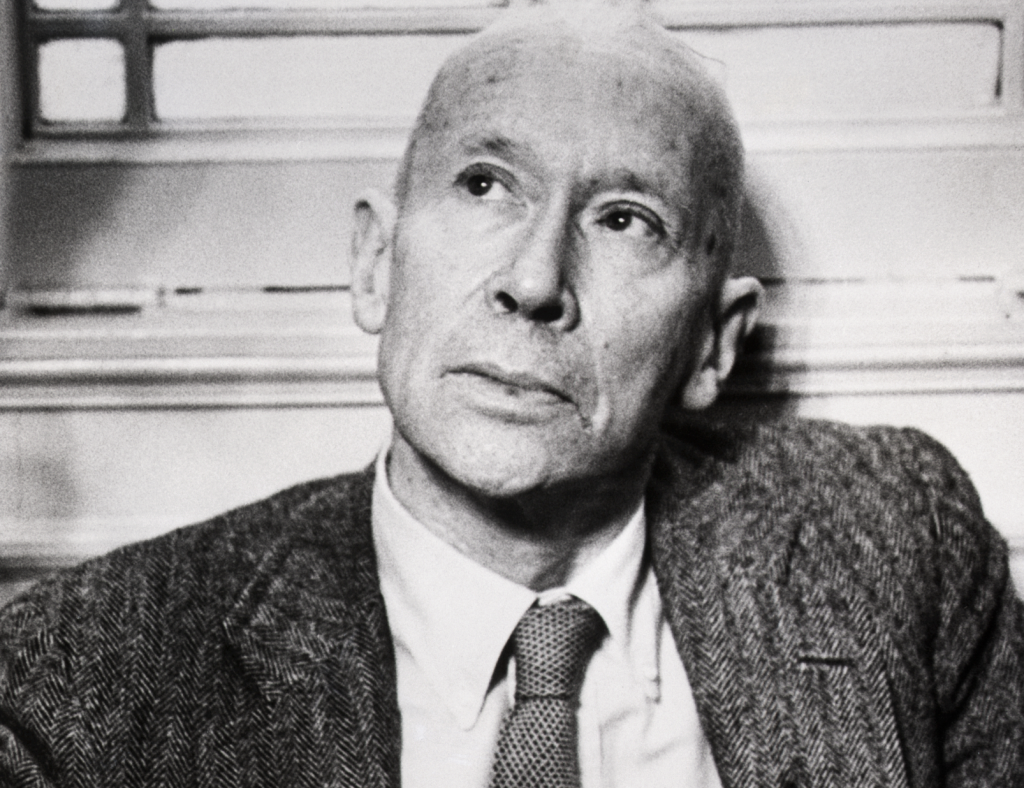

Original self-portrait by e.e. cummings and his music. March 30, 2007. Photo by David Jennings/Digital First Media/Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images.

Haskell estimated nearly 20 percent of the works in “At the Dawn of a New Age” are new acquisitions, including Henrietta Shore’s Trail of Life (1923). Just under half have been in storage for decades. Albert Bloch’s Mountain (1916), for instance, reemerged after a half-century in the archives to headline the show’s flier.

Hence cummings’s appearance alongside the likes of Yun Gee, “now considered one of the most important Asian American artists of the first half of the 20th century,” according to Haskell, and Pamela Coleman Smith, who showed with Stieglitz a year before he debuted Rodin’s watercolors.

The poet contributes an abstract oil painting titled Noise Number 13, featuring geometries and unexpected hues characteristic of the modernist aesthetic. He painted the work in 1925, upon returning from three years in Paris. Haskell sees the poet’s shock at the city in the cacophony in the painting.

Henrietta Shore, Trail of Life (1923).

After graduating from Harvard, cummings moved to New York City. He made line drawing portraits for Dial Magazine, and started showing modernist works at the Society of Independent Artists. Soon after, cummings saw a show titled “The Forum,” which presented 17 leading American artists of that moment, including Marguerite Zorach, who also appears in “At the Dawn of a New Age.“

“cummings saw that show,” Haskell said. “That inspired him to do much more radical, more abstract work.” Now, the artists are reunited at the Whitney.

Yun Gee, Street Scene (1926). Courtesy the estate of Yun Gee.

cummings kept painting with the same discipline throughout his life, but as his poetry picked up steam, his visual experimentation dwindled. He continued painting, but they were “much more conservative, realistic pictures,” Haskell said. “To be absolutely honest, they weren’t as good.”

Like cummings, the paintings practices of Pamela Coleman Smith, Henrietta Shore, and Agnes Pelton, who all appear in the exhibition, receded into the background by the 1930s. “That’s part of the story, too,” Haskell said, “that they were so good at that moment.” But their experimentation and faith in the future remain timeless.