Art & Exhibitions

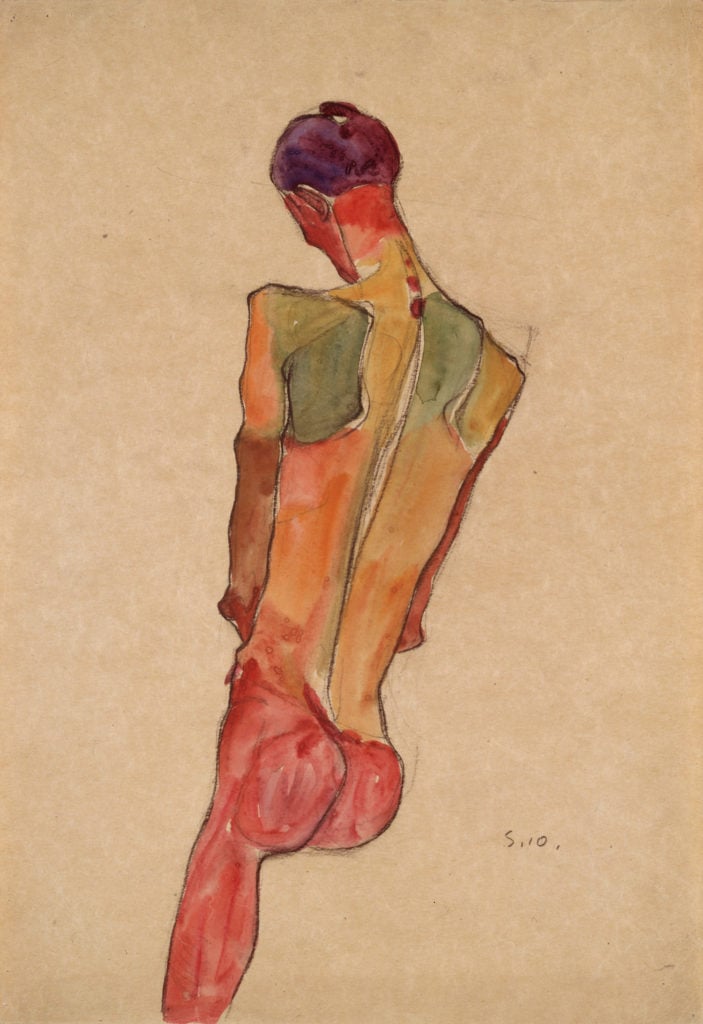

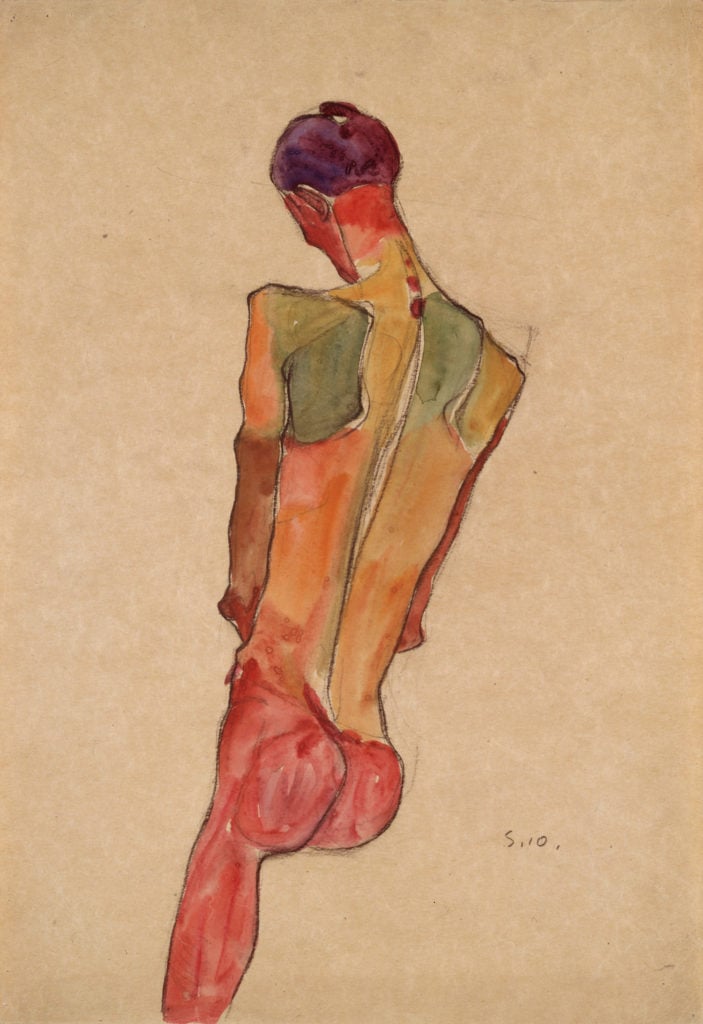

Schiele’s Male Nudes, Long Thought to Be Self-Portraits, May Have Actually Depicted Gay Models

Schiele scholar Jane Kallir is updating the catalogue raisonne to include new revelations on Schiele's "Red Men."

Schiele scholar Jane Kallir is updating the catalogue raisonne to include new revelations on Schiele's "Red Men."

Sarah Cascone

New scholarship has found that Egon Schiele’s male nudes from 1910, known as his “Red Men,” are not, as has long been assumed, self portraits. Instead, they most likely depict the artist’s gay friends.

Jane Kallir, author of the artist’s catalogue raisonné and co-director of New York’s Galerie St. Etienne, now believes that Schiele may have intentionally protected the identity of these men because homosexuality was illegal in early 20th-century Vienna. Schiele lived in a society where “the whole concept of any kind of homoerotic impulse was totally suppressed,” Kallir told artnet News. “It’s just something that no one would be able to openly demonstrate in any way, shape, or form.”

Kallir first came to suspect that Schiele himself was not the subject of his “Red Men” back in 2012. “Given the poses and the positions from behind and from above, in different kinds of twisted contortions, there’s no way he could be painting or drawing at the same time that he was modeling for these works,” she said, noting that the artist always drew from life.

At the time, however, Schiele had two close friends, Max Oppenheimer, who was gay, and Erwin Osen, who was bisexual. Although Kallir’s research suggests that Schiele may have also engaged in a homosexual sexual encounter in the summer of 1910, when he was 19, she’s not sure about the exact nature of his relationship with Oppenheimer and Osen.

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait with Brown Background (1912). Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne.

Kallir argues in essays accompanying Schiele exhibitions at Galerie St. Etienne and the Fondation Louis Vuitton, that one or both men likely sat for these works, though the gestural quality of the drawings particularly suggests in particularly Osen, who was trained as a mime. “What is clear is that these are his closest companions precisely at the moment that Schiele emerges with his first expressionist style,” she said.

“In his self-portraits, he always shows his face. They are an exploration of Schiele’s identity,” Kallir added. In contrast, these works “were personal explorations of human sexuality.”

Obscuring the sitters’ faces, Kallir believes, was a way of protecting their identity, for these aren’t merely renditions of male musculature. “Whatever they are about, they are not about anatomy,” said Kallir. “In a traditional male nude, you are going to use the figure in another work about the history of the Bible. Absent that kind of practical function, what is a nude about?”

Egon Schiele, Reclining Male Nude (1910). Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne.

Schiele’s legacy has always been wrapped up in notions of sexual transgression—and impropriety. In 1912, the parents of a young runaway girl accused the artist of statutory rape. The charges were dropped after police investigated, but they found that children had seen some of Schiele’s nude drawings on his walls and convicted him instead of public immorality. These abuse allegations have led in recent in months to some calls to reassess Schiele’s legacy.

“Essentially, the #MeToo movement has sort of taken this as an example of something that it does not in fact relate to at all,” said Kallir, who has not found any evidence of sexual misconduct between Schiele and the young girl. “One of the problems here is that the court records don’t survive. This is pieced together from fragmentary documents.”

The discovery about the “Red Men” is new evidence of Schiele’s sexually progressive nature. “It’s very interesting to see how contemporary Schiele remains in terms of the fluidity of how he deals with gender,” said Kallir. “He’s such an eternal artist, someone who’s discovered anew by every generation.”

“Egon Schiele: In Search of the Perfect Line” is on view at Galerie St. Etienne, 24 West 57th Street, New York, November 1, 2018–March 2, 2019.