Law & Politics

Prominent Artist eL Seed Says the Tunisian Pavilion at Dubai’s Expo 2020 Used His Work Without Permission

The case illustrates a growing tension around the ownership of calligraphic script in the digital era.

The case illustrates a growing tension around the ownership of calligraphic script in the digital era.

Rebecca Anne Proctor

The Dubai-based French-Tunisian street artist who goes by the name of eL Seed has accused the Tunisian pavilion at Dubai’s World Expo, which opened on October 1, of copyright infringement of an Arabic calligraphy design. While the creative agency responsible for the pavilion, Dix Versions, has denied wrongdoing, the case—which the artist intends to pursue in court—highlights the complexity of ownership when it comes to Arabic script, which may be considered a stylized typeface or an artistic creation, depending on context.

On Monday, October 11, eL Seed published on his Instagram account a statement explaining how in 2019, he was approached by British architectural company Pico, encouraging him to work with them on a proposal responding to the call for the design of the Tunisian pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai. Their proposal—a design featuring eL Seed’s calligraphic forms—won, and was planned to appear on the façade of the pavilion.

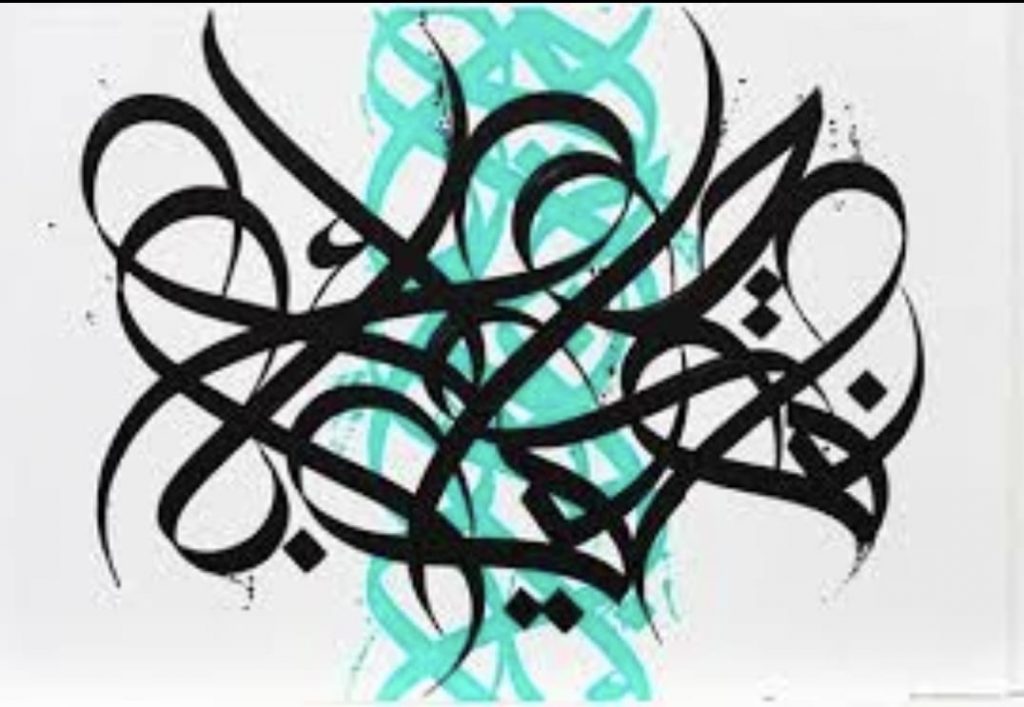

Artist eL Seed’s 2019 calligraphic design for the Tunisian national pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai.

According to eL Seed, in October 2020 Pico told him that the Tunisian Export Promotion Center (Cepex), which oversees the national pavilion, had changed its board and wanted to make a new call for proposals.

“I called up Cepex to understand better, and they told me not to submit with Pico and to work directly with them,” eL Seed told Arnet News. “They said ‘Make a proposal with Pico and we will kick them out and you can work just with us.’ My professional integrity didn’t allow me to do so, and so that’s how it ended.”

eL Seed declined to submit work in the second design call. However, when the artist visited Expo 2020 (which was postponed to 2021 due to the pandemic) he was shocked to find that his initial proposal had been used for the façade without his authorization. “They took the concept I proposed for the façade, flipped it, and then merged it with work of another artist,” he wrote on his Instagram post, which he has since taken down on the advice of his lawyer while the case is investigated.

A rendering by Dix Versions for the exterior of the Tunisian pavilion at Expo 2020 in Dubai.

Leading Tunisian creative agency Dix Versions, whose proposal won the 2020 call, has contested eL Seed’s story. “Cepex asked all designers responding to the call, both in 2019 and 2020, to incorporate Arabic calligraphy in their proposals, and that is what we did,” Alya Bouzid, architect and concept creator at Dix Versions, told Artnet News.

“We created an artistic parody by incorporating examples of Arabic calligraphy and elements from eL Seed’s work,” she added. “For us, eL Seed is an icon and inspiration. We used several elements from his work—namely the superimposition of Arabic graphic calligraphy—for our proposal to make our artistic parody. We did not copy an entire work by him, and so we did not need to ask his permission.”

eL Seed is renowned globally for large-scale public artworks that employ the aesthetic traditions of Arabic calligraphy as tools for political and cultural awareness. He has said that his hope is to spark “a dialogue between cultures” and for his work to foster social change. His major public works include The Bridge, created along the security fences of the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea; a painted rooftop in the Vidigal favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Perception, a calligraphic mural in the Cairo neighborhood of Manshiyat Nasr, and Mirage, a large sculpture created for Saudi Arabia’s Desert X Alula in January 2020.

Detail of Dix Versions’ rendering of the exterior of the Tunisian pavilion at Expo 2020 in Dubai.

Although Arabic calligraphy has been practiced by artisans since the 6th century BCE, in today’s digital world, appropriating or copying contemporary calligraphic script without the license of its originator is becoming more problematic. The dilemma over the design of the Tunisian pavilion raises issues around what, exactly, constitutes copyright infringement. According to eL Seed, the work he created for the pavilion’s proposal was used, whereas Dix Versions states that only elements were incorporated.

According to IP specialist Mark Hill, a partner at Charles Russell Speechlys’ Middle East office, “Disputes on the copyright which arise in relation to calligraphy as a work of fine art can be pretty broad, including the unauthorized publication of a reproduction, including in digital form, of the original work; the unauthorized inclusion of any underlying 2D work in a 3D sculpture form; inclusion of an underlying work in the design of textile patterns and designs, etc.” He went on, “As we move into an era where there is also so much discussion of the NFT incorporation or digital reproduction of art, there remains a core principle in my view, namely that permission of the owner of the rights in any underlying artwork is always required where a reproduction or inclusion of that original work is happening. Calligraphy created in a fine art context is art, and it should be protected as art.”

It’s not the first time that eL Seed has become embroiled in the appropriation debate; the in-demand artist says his work is often copied without his permission. eL Seed believes around 10 companies in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC states) have stolen his work in the past few years. He maintains that he’s been told that if he speaks up, they will sue him for defamation. “Governments in the GCC and all over the world need to condemn these unlawful practices of copyright infringement,” the artist told Artnet News.

“I am very picky about the brands I collaborate with,” he added. “So many artists put so much work into their art and then it gets stolen. The people who steal the artwork are paid for it, so they get money for work that isn’t theirs. For the image of the artist, this is very damaging.”