People

‘I Had to Fight to Show What I Could Do’: How Elias Sime Emerged as One of Africa’s Leading Contemporary Artists

The artist, who has been tapped by Ethiopia's Prime Minister for a major project, is also a Hugo Boss Prize nominee.

The artist, who has been tapped by Ethiopia's Prime Minister for a major project, is also a Hugo Boss Prize nominee.

Will Fenstermaker

Five years ago, the Ethiopian artist Elias Sime, who is known for his sculpted aerial landscapes and river scenes and colorful striated patterns, didn’t have gallery representation in New York.

Sime had shown work regularly in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa since the 1990s, and was included in group shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Studio Museum in 2008. A year later, theater director Peter Sellars commissioned the artist to stage his production of Oedipus Rex, which inspired a 2009 retrospective at the Santa Monica Museum of Art. After the show, Sime turned his focus to making new work back home.

Five years later, Meskerem Assegued—an anthropologist and Sime’s longtime collaborator, who curated the show in Santa Monica—was introduced to New York dealer James Cohan by the writer Lawrence Weschler. Cohan asked to visit the LA warehouse where Sime’s works were stored.

“How often is it that you encounter someone who’s got 25 years worth of fully realized work, and you get to make an assessment?” Cohan asked me. He called the artist and asked to represent him. “It was a no-brainer.”

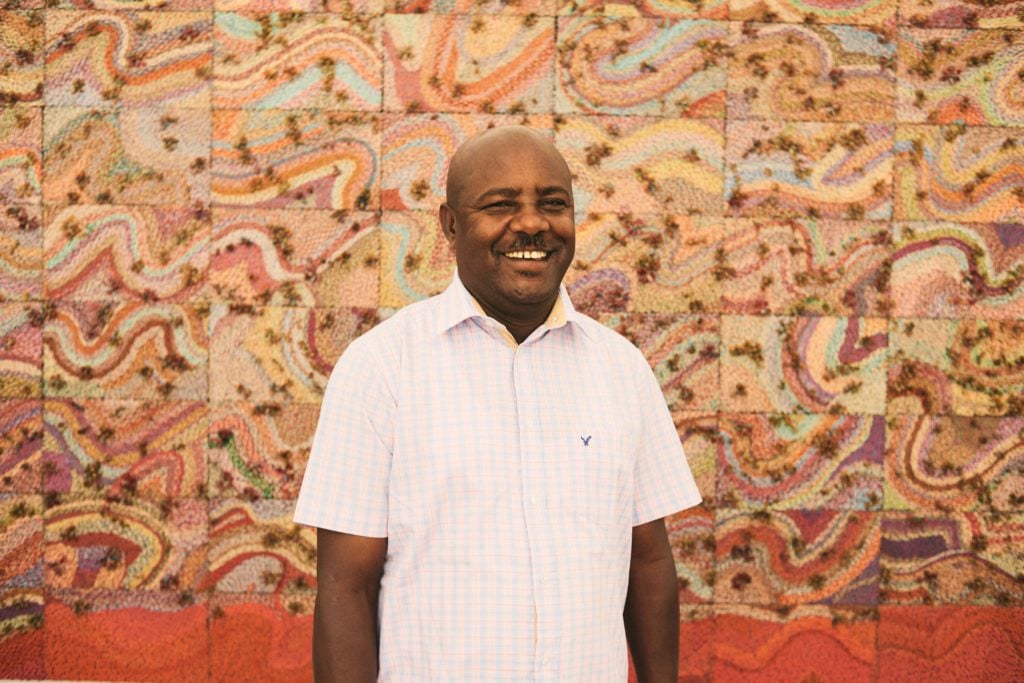

Works by Elias Sime in his exhibition, “Noiseless,” at James Cohan gallery in New York in 2019. Phoebe d’Heurle.

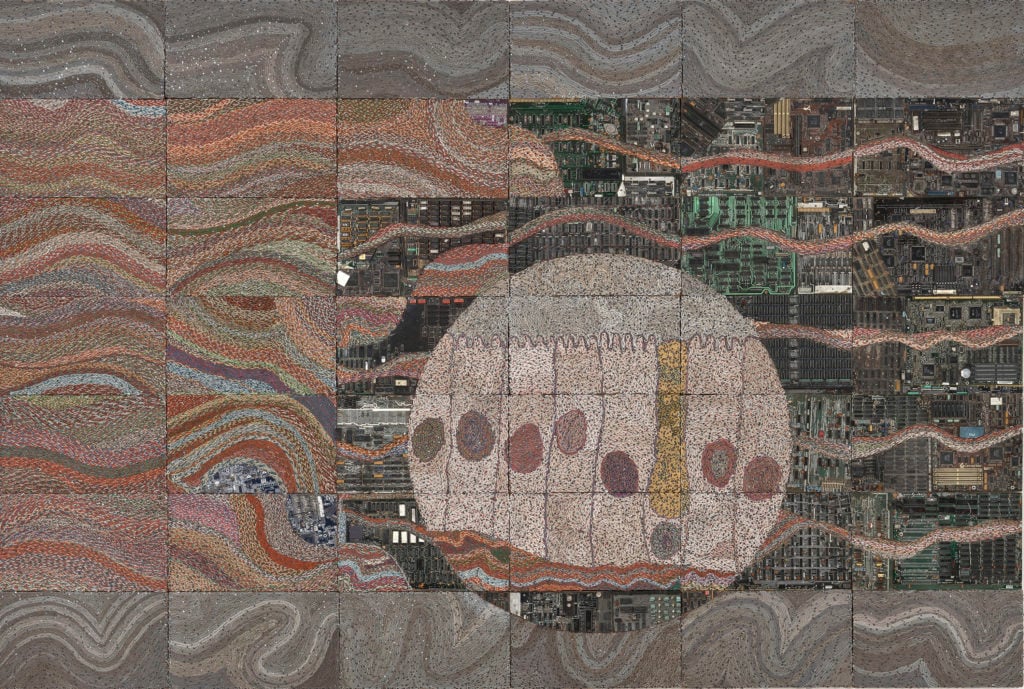

Cohan hosted Sime’s first US gallery show in 2015. From that exhibition, the Met became the first public collection in the US to purchase one of his artworks, which are made of braided electrical wires, motherboards, keyboards, buttons, canvas, and carved wood panels. And suddenly it seemed that everyone wanted a Sime.

In North America, he’s currently the subject of a traveling exhibition organized by Tracy Adler at Hamilton College’s (temporarily closed) Wellin Museum. Facebook recently commissioned him to make a 63-foot mural for the company’s Frank Gehry-designed Menlo Park headquarters.

In October, the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art commissioned several works to inaugurate its redesigned pavilion, and in April (assuming the museum is open then), he will open a solo exhibition at the St. Louis Art Museum, where Sime will show new sculptures inspired by the nearby pre-Columbian Cahokia Mounds. (The works are based on research by Assegued.)

On top of all that, Sime—who is quickly becoming recognized internationally as one of Africa’s leading contemporary artists, alongside El Anatsui and Wangechi Mutu—was shortlisted for the Hugo Boss Prize in November.

But one of Sime’s biggest projects is being undertaken back home, where he and Assegued have spent much of the past few years working to re-establish Addis Ababa as a preeminent city for contemporary African art.

Elias Sime, Tightrope: Internalized (2017). Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York.

Last May, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed visited the Zoma Museum in Addis Ababa, which Assegued and Sime cofounded in 2019. Within a week, Ahmed commissioned the pair to construct two gardens in the city: one at the Allé School of Fine Arts and Design, and the other at the Menelik Imperial Palace.

“Think about it: here’s the Prime Minister telling you what to do,” Assegued told me on the phone from Addis Ababa. “He wanted it done in a month, which was an impossible task, but we got into it right away.” The garden at Allé was finished last fall, and work at the palace should be done by this summer. “I feel strongly that the public will see the gardens as collaborative works between us,” Sime said.

The sites for the two parks are important for the artist. Sime enrolled at the Allé School of Fine Arts and Design in 1986, during the final years of Ethiopian communism. By then, many artists had been forced into exile.

But the university’s professors, who were fluent in Russian, expected their students to paint images of Lenin and to adhere to Socialist Realist conventions. Sime’s experimentation with materials was verboten, and his teachers discarded much of his university work. But there was no alternative school to attend, and if he wasn’t a registered student, he would be conscripted into the army and placed on the front lines of the civil wars raging throughout Ethiopia.

So Sime stayed.

“In retrospect, my teachers’ control helped me think differently,” he said. “I had to fight to show what I could do, and I had to wait until I graduated to do it.”

When Sime finished his schooling in 1991, the Soviet Union had just ended support of the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Marxist rule collapsed that May.

Works by Elias Sime in his exhibition, “Noiseless,” at James Cohan gallery in New York in 2019. Phoebe d’Heurle.

Sime, who was born in Addis Ababa in 1968, has made sculptures from various materials since he was a boy. “His hands are everywhere in his childhood home,” Assegued said. “Even the coffee table is completely carved out.”

“It was always one thing leading to another,” Sime said of his development. “When I started working with fabric, I had a bunch of string and buttons. So I added the buttons. And then I had to stitch them, and it looked pretty good. It was smooth, like painting.”

“Elias’s work is beautifully crafted,” Cohan said.

But he and Sime are quick to condemn the superficial narrative of “up-cycling” that’s often applied to African artists who repurpose waste. Critics have suggested that artists from developing nations who work with scraps, such as Sime and El Anatsui, posses a down-to-earth simplicity and redeem a global economy that has pushed the world to the brink of ecological collapse.

But Sime’s intention isn’t to turn waste—electronic or otherwise—into sublime compositions. Rather, he wants to tell stories about our relationship to the earth and to each other. A landscape of braided wire represents connectivity, but also the extraction of rare minerals from the earth and technology’s intervention into our social order. Sime repurposes materials without irony, and Assegued says he braids wires the way another artist mixes paint.

Unity Park in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Photo: Aron Simeneh.

In newly democratic Ethiopia, Sime was able to follow his own rules. But 17 years of military rule had damaged the country, which was once a bastion of modern art. The Imperial Palace where Sime and Assegued are constructing their 15-acre park was used a torture site under the Derg military junta.

But Ahmed, the prime minister and a Nobel Peace Prize winner, understands the political power of art. Last October, he reopened the Palace as a public park with a national museum to strengthen unity among the country’s nine semiautonomous ethnolinguistic regions. At its center is Sime and Assegued’s Unity Park.

“Opening up the seat of power speaks volumes about what the government is up to,” Cohan said.

Like Sime’s constructions and sculptures, Unity Park is embellished in extraordinary detail: Every stone is hand-carved and based on Sime’s drawings. Benches and buildings are wreathed in filigree. Ornamented pathways cut through terraced gardens. Even the restrooms were carved by masons using ancient techniques.

“When you come there, you see a wholesome thing,” Assegued said. “Thousands of people walk in every day. They can’t believe they’re inside a building that they feared for so many years.”

“Here they can see,” Sime added, “that we thrive by working together and sharing our knowledge.”