Up Next

Painter Emma Webster Uses the Art of Illusion to Transform Jeffrey Deitch’s L.A. Gallery Into a Theatrical Environment

The solo show, titled "Intermission," opens September 8 in Los Angeles.

The solo show, titled "Intermission," opens September 8 in Los Angeles.

Katie White

British-American artist Emma Webster is taking us backstage, showing us how a painting is made.

In “Intermission,” the Los Angeles-based artist’s new solo show at Jeffrey Deitch’s Santa Monica gallery, Webster has performed a kind of magic trick, transforming the jewel-box gallery space into a theatrical space, one that feels behind-the-scenes and center-stage all at once.

“I was given a carte blanche opportunity to transform the gallery, which is very rare,” said Webster, with palpable enthusiasm. “The space itself used to be a recording studio, so I thought, if the architecture is already there, we’re going to build a theater inside. And ‘Intermission’ had to be the title of the show, I knew, because I love the disorienting moment in a theatrical production—right after a moment of crisis, or climax—when the lights come up and the audience doesn’t know what to do.”

Emma Webster in her studio.

Webster’s paintings—tempestuous, seductive landscapes that conjure up comparisons to the 19th-century visions of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and the sublimity of Frederich Edwin Church—are positioned, staged we might say, throughout the gallery-like backdrops and scenography. Meanwhile, black-and-silver road cases are piled in corners. Costumes hang on a dressing rack. At the center of the gallery, Webster has built a compact, black box theater.

“We think of a mask as a prop, but here, the architecture of the theater is also a prop. The casting sheets and the benches and the mirrors and all that. It’s the idea of a meta-prop or a meta-set. The last room in the gallery is this hidden little projection room that has a Phantom of the Opera aura and that’s where I’m showing very, very small paintings,” the artist detailed.

“Intermission” marks Webster’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles in over four years, and in its eagerly anticipated fruition is an ambitious, heady journey through the creative process, which explores the tensions between painting and artifice, landscape and staging, art and object, and ways we navigate the two- and three-dimensional tango of our digital age.

Installation view “Emma Webster: Intermission” at Deitch Gallery, Los Angeles, 2023. Photograph by Joshua White.

Webster, who earned her M.F.A. at Yale in 2018, has come to be known for luminous oil paintings of landscapes that aren’t really landscapes at all. Instead, Webster’s works are the culmination of a unique process that blends drawing, virtual reality, and sculptural models. “Her studio is a fascinating combination of a computer lab and a Renaissance artist’s atelier,” the gallery wrote in the statement for the exhibition.

Using software like Oculus and Blender as draft-making tools, Webster creates her own imaginary worlds in virtual reality, which she both inhabits and morphs. When she completes these visions, she then meticulously translates her images onto canvas by hand. For Webster, the process can be nerve-racking.

“A theatrical intermission is sort of like my process,” Webster explained, “It’s a sudden shift in realities. You go from the hypothetical world to the real world, abruptly. Then you’re meant to take a bathroom break. You get a drink of water…but there is still the assumption that the resolution is coming.”

For the artist, that moment of resolution, of bringing the virtual reality landscape onto the canvas, can be fraught. “The doubt resurges with extra power because I’ve already gone through a stage of conviction. I think a lot of people wait for the conviction to happen in the actual painting. There is a back and forth: I thought I believed in it, but now I don’t believe in it. I thought I believed in it,” said Webster. “I’ve been trying to be better about hanging onto paintings that might be challenging.”

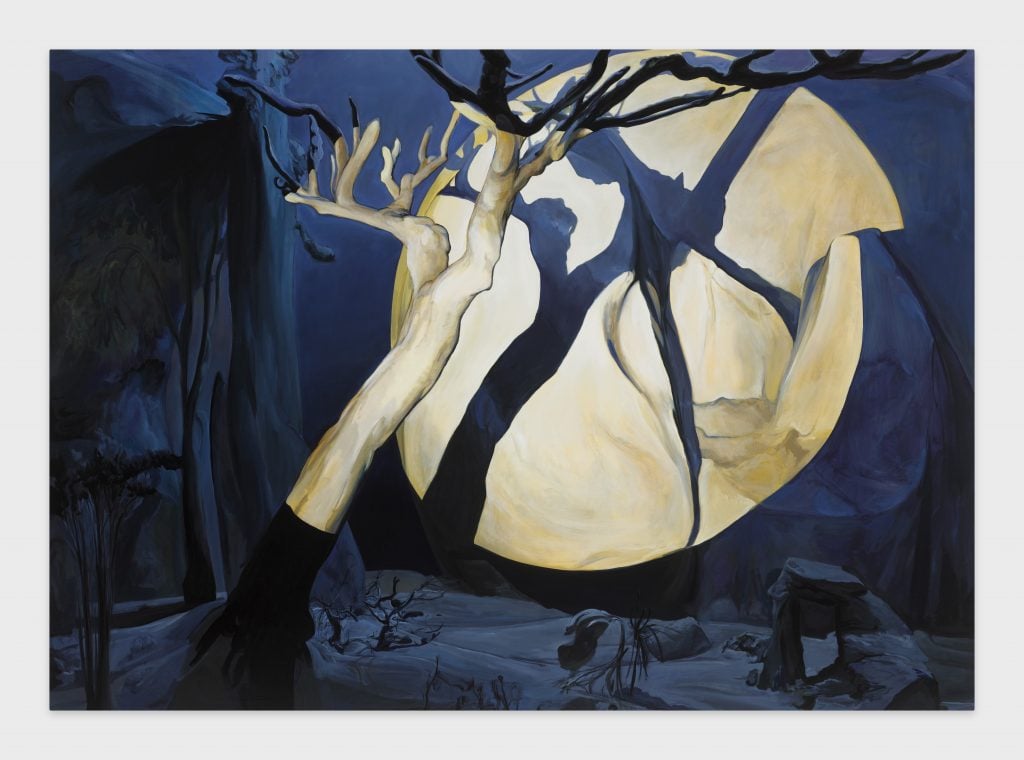

Emma Webster, The Rehearsal (Harvest Moon) (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch.

Her complex practice entwines landscapes, theater, virtual reality, and painting itself into a labyrinth of perception and experience. Webster’s resulting landscapes are, as she puts it, “optically devious” and engage with a long history of trompe l’oeil painting in a new and inventive way; in her works, the tactility and sensuality of her brushstrokes, and oil paints, in their myriad hues of synthetic greens, imbue her landscapes their only realness.

Webster’s interest in theater is longstanding. After finishing her undergraduate studies at Stanford, Webster spent time working at the La Jolla Playhouse, designing theater sets, a job that would offer glimmers of inspiration for works she wanted to create. While at Yale, Webster began building maquettes, dioramas, and puppet-sized theaters, a kind of world-building that offered her a release from painting. Eventually, a classmate introduced Webster to virtual reality as a more efficient and powerful tool for creating the simulacra that she was after.

“When talking about the evolution of my work from building papier-mâché sets to working in virtual reality and on the computer, the reality is that it comes with a lot more freedom and physicality. What you can do digitally is just one language. I find there is still the opportunity to take all these new techniques from different sculptural practices at adapt them into the language of the computer, whether it’s sculpting with marble and you’re chipping away or sculpting with clay and it’s additive. It brings in a tangential, hobby-like aspect to my process, whereas the painting is where the elegance of everything comes together.”

Installation view “Emma Webster: Intermission” at Deitch Gallery, Los Angeles, 2023. Photograph by Joshua White.

The pandemic, Webster acknowledged, gave her time to immerse herself in perfecting her VR capabilities, and offered her, in her own words, an intermission from the demands and expectations of every day, when she was given the time and space work.

In her landscapes, Webster has earned comparisons to everything from the paintings of Albert Bierstadt to the animations of Disney films, and she has embraced these far-flung and fantastical elements and fundamental counterpoints in her practice. “I was born in San Diego, but my dad is English and I had this feeling of being tied to a completely different world. Everything was always so green and lush and wet when we would go to England for summer and to visit my grandparents. But it didn’t feel like mine. And in the same way, San Diego just felt strange, too,” Webster explained. “They’re both idyllic in different ways, you know?”

For Webster, her works become ways to free the landscape itself from expectation. “I want to liberate painting and bring the conversation back to the image instead of the art object and emotion,” she said. Part of that is letting the viewer in on how objects are made, how even in the virtual realm—dress rehearsals, if you will—are essential. “I want to trust in the viewer and give them as much information. Vulnerability is great. We need ugliness, poor taste, and bad decisions sometimes. It’s humanizing and crucial. Even in my practice, there’s the refinement of the sculpting and the lighting and the image. But at the end of the day like, I do want there to be flaws. I don’t trust art without flaws. Where’s the process?”