Art World

In the 1970s, an American Curator Moved to Tehran to Advise the Empress on Her Art Collection. Here’s What They Bought

Read an excerpt from Donna Stein's new memoir, "The Empess and I."

Read an excerpt from Donna Stein's new memoir, "The Empess and I."

Donna Stein

Donna Stein, a former curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, advised Empress Farah Diba Pahlavi on her art collection in the 1970s, and helped forge Iran’s national contemporary. Below, read an excerpt from her new memoir, The Empress and I, about her experiences in Tehran.

I finally signed my second contract in January after five weeks of aggravation and indecision. It was still a difficult choice, but somehow seemed like the best alternative. During a conversation, Dr. Pasha Bahadori, [the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art’s chief of staff,] told me that he was very pleased with my work, liked me personally, and enjoyed working with me. I knew such compliments were quite unusual and it was energizing to learn he thought I was making such an important contribution. As I expected people to be uncomplicated and honest, I was too naïve to realize at the time he was probably flattering me. As much as I disliked some aspects of my situation, I couldn’t face not knowing what I was going to do next. Nevertheless, I made sure I had an escape clause that permitted me to depart after giving three months notice. I also negotiated a 15 percent raise. Dr. Bahadori told me the salary was equivalent to his executive assistant’s earnings after sixteen years of loyal service.

In early January, John Hightower visited Tehran to interview for the job of the director of the Tehran museum. Our paths hadn’t crossed much since I had worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York during his directorship. Hightower was in town for three days and I spent most of his visit escorting him around town and introducing him to collectors, artists, and galleries. When Mr. Hightower left I wrote to a mutual friend “I think it is highly unlikely that he will take the job.”

On the first day of 1976, I supervised the opening of several crates to find La Soupière de Moustiers (1938–39), a beautiful still life painting from André de Segonzac’s mature period that had been purchased in New York the previous year. Dr. Bahadori agreed to lend this canvas to a retrospective exhibition at the Orangerie des Tuileries in Paris, making it the first work from the growing collection of Iran’s museum to be exhibited abroad.

The word got out about what I knew and could do, and my willingness to help colleagues turned me into a ubiquitous resident curator around town. Several Iranian artists, gallery dealers, and collectors asked for my help advising, installing their shows, and writing catalogue essays for exhibitions and thereby allowing me to do the work I liked best. I met Ghasem Hajizadeh in New York and we have remained friends ever since. When I moved to Iran he introduced me to many Iranian artists, galleries, and aspects of life in Tehran. I was happy to design the installation for Hajizadeh’s exhibition at the Goethe-Institut as well as write a catalogue introduction for another exhibit hosted by the Iran American Society. It was my pleasure to introduce artists such as Ardeshir Mohasses and Shahrokh Hobbeheydar Rezvani to art world colleagues in the United States. Among other efforts, I also advised on Sonia Balassanian’s installation at the Negarkhaneh Saman. Before leaving on a trip, I stopped by the Zand Gallery on my way to the railroad station to see how the hanging of their first show featuring Michalis Macroulakis was going and ended up redoing everything and almost missing my train.

The Saman Gallery, one of several new galleries in Tehran, opened in my apartment complex that March. The gallery owners were among Iran’s elite families and their impressive inaugural exhibition featured artists like Claude Monet and Max Ernst. Her Majesty attended a special preview to which I was also invited and she selected Le Ciel (1934), a small oil on wood painting by René Magritte. For two or three days in advance of the event, preparations began to secure the gallery and investigate the building staff. The night of the opening I made sure to have my picture ID from the Private Secretariat in my pocket featuring the gold emblem of Her Majesty. The elevator operator asked where I was going all dressed up. When I pulled out my ID card, he exclaimed, “You’re going? You work for Her Majesty?” In that moment I realized the building staff was totally unaware of what I was doing in Tehran and only knew me as a foreigner they dubbed “the woman who lives alone.” This unfortunate phrase was also used to describe women of questionable virtue, as it was inconceivable that a woman would live by herself, and anyone who lived apart from their families was clearly an outcast. As soon as I walked out of the elevator, the attendant told everyone that I was working for the Empress.

Paul Gauguin Still Life with Japanese Woodcut (1889).

In the meantime, my art collecting activities proceeded apace. Three major paintings were purchased at record prices from the Sotheby Parke-Bernet auction in March from the Estate of Josef Rosensaft: Gauguin’s Still Life with Japanese Print (1889); Rouault’s Trio (Cirque) (1938); and Kees van Dongen’s Trinidad Fernandez (1910).

I was thrilled that we obtained the Gauguin, which I considered among his greatest still-life paintings. Ambroise Vollard, his French dealer, lent the canvas to the New York Armory Show in 1913—an historic exhibition that shocked the world and changed our perception of beauty. This key transitional canvas created between the artist’s Brittany and Tahiti periods demonstrated his interest in Japanese ukiyo-e woodcuts and primitive art, thereby anticipating the cross-cultural dialogue that shaped the philosophy of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. In addition, the earthen-ware jug depicted in the middle of the composition served as an intriguing self-portrait of this pioneering French artist and Van Gogh’s best friend.

Georges Rouault’s Trio (Cirque) is a late work in the Expressionist style. The artist’s fascination with circus clowns dates from the turn of the century and was part of his focus on depicting human nature. As one journalist noted, “the robust central figure, with her striking arrangement of Mesopotamian wedge nose and saucer eyes, might have been unearthed at Ur.” I successfully argued that Trinidad Fernandez by Kees van Dongen was an exemplary painting, which would provide all the important visual clues any viewer might need in order to fully appreciate his work. In the exhibition “All Eyes on Kees van Dongen,” the painting was re-dated from 1907 to 1910, the year that the artist traveled to Spain and Morocco, and is one of a group of lively portraits of women wearing colorful shawls. Purchased from the artist by his gallery the year it was painted, this series was exhibited in Paris at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, where Van Dongen had a solo show in 1911. Around the time he traveled in Spain and Morocco, French dealers like Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Bernheim-Jeune were aggressively promoting a rage for exoticism and Orientalism. Many artists, including Paul Klee, August Macke, Henri Matisse, Alexei Jawlensky, and Max Pechstein traveled to Spain, Morocco, and Tunisia in the years that followed.

Mark Rothko’s Sienna, Orange and Black on Dark Brown (1962) was purchased at auction in May at Sotheby Parke-Bernet in New York. About the same time, another exemplary Rothko canvas from a slightly earlier period, No. 2 (Yellow Center) (1954) was purchased from a private collection in Liechtenstein. I remember vividly paging through a traveling exhibition catalogue looking at a number of paintings that were displayed in Zurich, London, and Paris, selecting this imposing canvas from a group of works that were offered for sale. In these classic meditative paintings from the New York School for which Rothko is best known he forcefully manipulated form and space to expressive ends. Their formality charts the artist’s steady course into pure abstraction during the post-World War II period. Incidentally, Rothko’s No. 2 was lent to the Guggenheim and impounded by the American government at the time of the Islamic revolt in 1979.

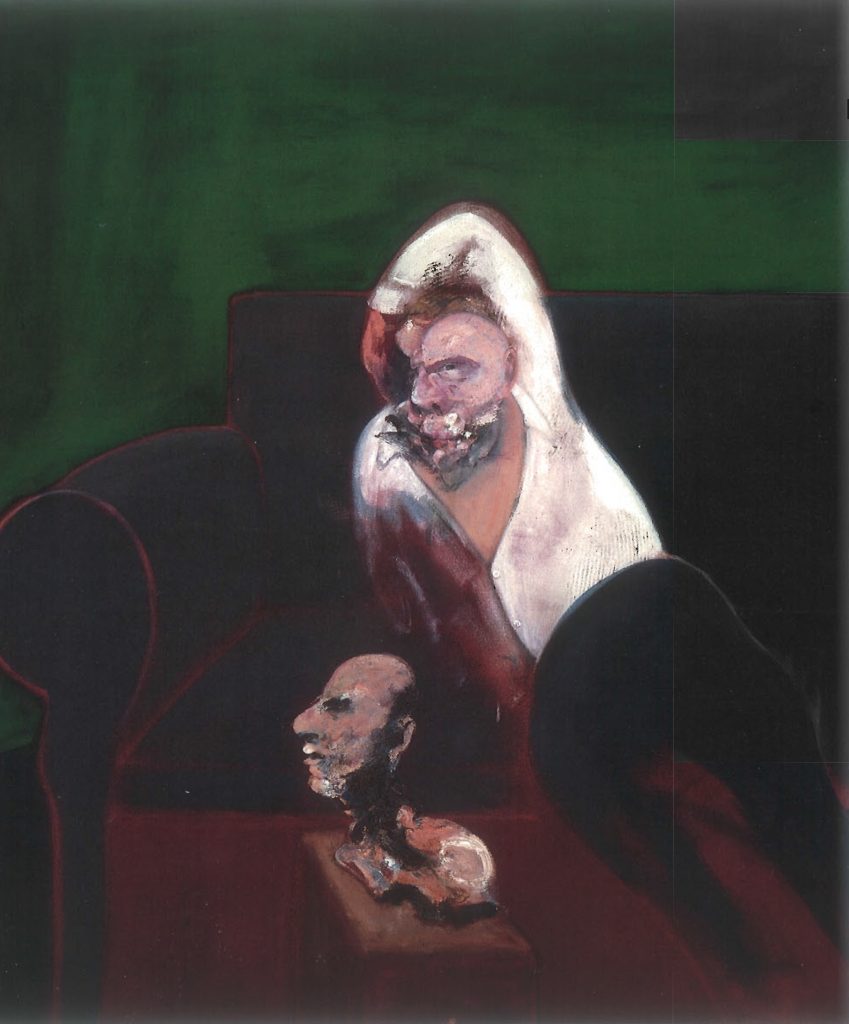

Francis Bacon, Reclining Man with Sculpture (1960-61).

After studying Francis Bacon’s work in a retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum the previous year, I was enthusiastic about acquiring one of his exemplary oil on canvas paintings for the National Collection at the same auction sale in New York as the 1962 Rothko. Reclining Man with Sculpture (1960–61) was first shown in American and International Art Since 1955, a group exhibition held at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. The man depicted in this canvas may be the artist or Peter Lacy, one of his favorite models who had been a fighter pilot in the Battle of Britain. The placement of the sculptured bust on a stool was the forerunner of domestic items Bacon introduced into his compositions to balance their violence, and may also reference bronze busts of the artist produced by William Redgrave in 1959. In 2005, TMoCA lent this painting to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh.

Excerpted from The Empress and I: How an Ancient Empire Collected, Rejected and Rediscovered Modern Artby Donna Stein, published by Skira Editore.