Art History

Meet the Man Who Snapped the World’s First Photograph of a Ghost (Or So He Claimed)

This edition of "Eureka" goes into the darkroom of spirit photographer William Mumler.

This edition of "Eureka" goes into the darkroom of spirit photographer William Mumler.

Min Chen

William Mumler couldn’t explain it. He was having his first go at the photographic process, when a self-portrait he had taken developed to reveal a mysterious apparition of a girl by his side. Mumler was alone when he photographed himself in a friend’s studio—what or who then was this spectral figure? Unfazed, he shared the picture with his friends as a lark. That is, until it reached a spiritualist journal, which decided he had captured, quite obviously, a ghost.

Where the spiritualists saw a ghost, Mumler eyed a business opportunity. At this point in 1861, the Boston-based silver engraver and amateur chemist already had behind him a host of dubious ventures, including a homemade potion that he sold as a dyspepsia cure. With his accidental creation of the world’s first haunted portrait, Mumler would inadvertently pioneer the field of spirit photography—and its attendant industry.

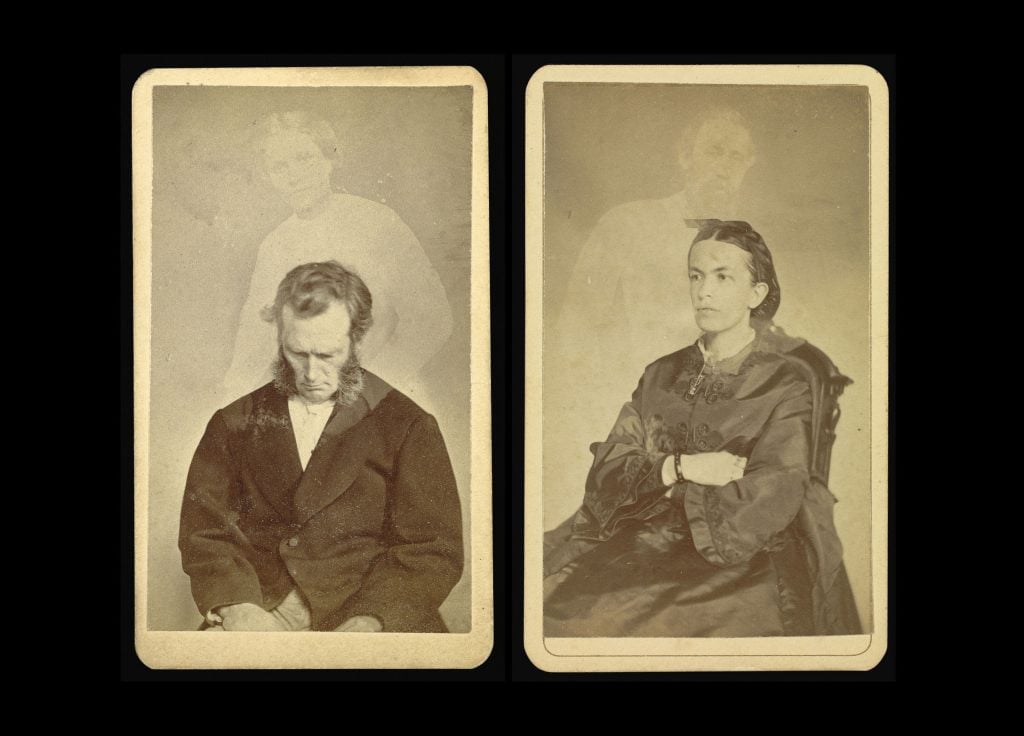

A spirit photograph attributed to William Mumler, 1862–75. Photo: Sepia Times / Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Mumler was soon charging Bostonians $10 to have their portrait taken alongside their dearly departed (or some likeness of). The origin story of his first spirit photograph grew embellished: the ghostly presence he captured was actually that of his cousin, deceased for 12 years, he said; his arm had also become numb when he took the picture. At his new full-time gig, he claimed he could only shoot a handful of spirit photographs a day, because communing with spirits was just so wearying.

All that, of course, was elaborate window dressing for the technique Mumler employed in the dark room. While creating his first self-portrait, he had unintentionally used a plate—a surface coated with a light-sensitive emulsion, in use in early 19th-century photography—that was already exposed and had not been cleaned, resulting in superimposed images. Mumler quite likely shot his sitters using similar double exposures, though his exact method and the chemicals he used remain unknown.

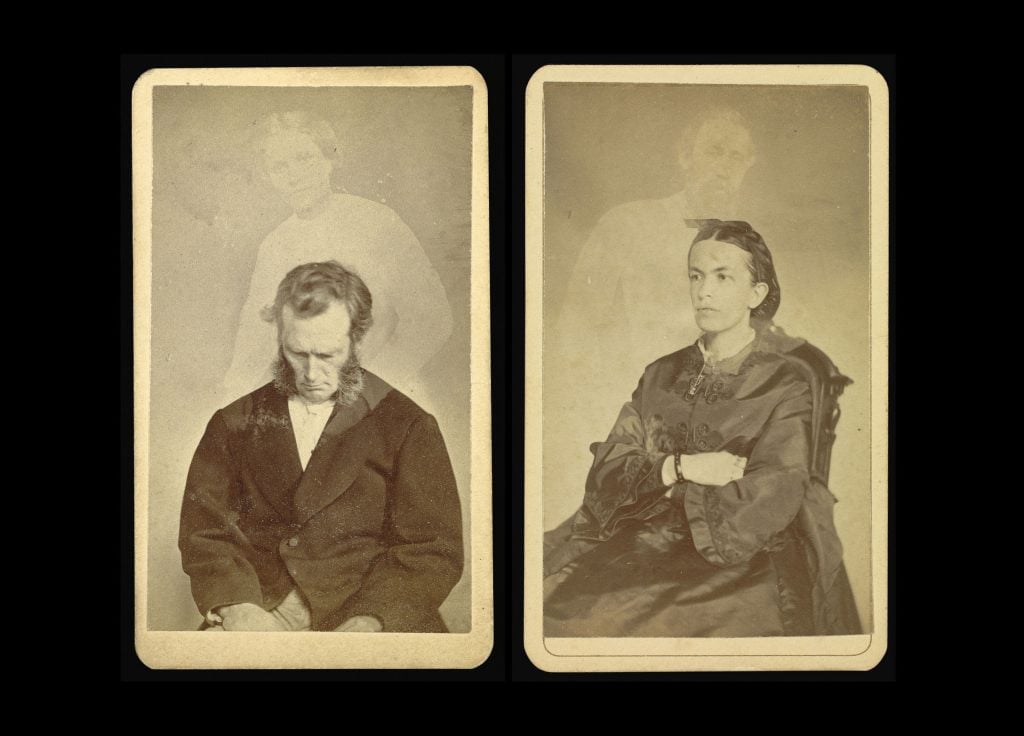

A double exposure photograph, ca. 1865. Photo: London Stereoscopic Company / Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

Photography, at this juncture, was a relatively novel phenomenon. The daguerreotype, the first widely available photographic process, was merely decades old, while advances in the field—from aerial photography to motion photography—ushered in previously undreamed-of perspectives. The public was wowed if mystified. Mumler’s clients were credulous.

“Mumler sold himself as someone who could not explain what was happening or why he was chosen to take these pictures,” Peter Manseau, author of The Apparitionists, told the History Channel. “He was as astonished as everyone else that suddenly his camera could take pictures of ghosts.”

William H. Mumler, Mr. L.A. Bigelow (ca. 1870). Photo: Sepia Times / Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

For two years, Mumler ran a lucrative enterprise—then the skeptics arrived. A doctor who had sat for the photographer in 1863 recognized the ghost in the subsequent picture as that of his wife, still among the living. A woman’s spirit photograph captured her brother who was lost to the Civil War, except he returned home later very much alive. P.T. Barnum, the famed showman, was but one voice roundly denouncing Mumler for exploiting the grief of his customers.

In 1869, the spirit photographer was tried for fraud, but later acquitted after the prosecution failed to prove how he created his pictures. Mumler, in his testimony, insisted: “I have never been in any humbug business where I did not give value for the money.”

A spirit photograph by William Hope, ca. 1920. Photo: SSPL/Getty Images.

While the trial did sully Mumler’s reputation, it could not staunch the development of spirit photography. His process, or grift, was taken up by medium-photographers from Édouard Buguet in France to William Hope in the U.K. In fact, Mumler continued to receive clients at his studio through the early 1870s—most notably Mary Todd Lincoln, widow of Abraham, who reportedly arrived under an assumed name. His portrait of Mary Todd, clad in a black cape with the white apparition of her husband hovering behind her, remains his most famous. It was the last photo she sat for.

William H. Mumler, Mary Todd Lincoln (untitled spirit photograph with Abraham Lincoln’s shadow) (ca. 1870s). Photo: Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum, Transfer from Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library, Bequest of Evert Jansen Wendell

More enduring, perhaps, was Mumler’s later invention of photo-electrotype plates—using woodcuts on a printing press as opposed to traditional etchings—which facilitated the printing of photographs onto newsprint, a revolution for the publishing trade. By then, his spirit photography days were behind him, as business and interest in spiritualism dwindled in the post-Civil War years. He had conceived of this latest technique, which he dubbed the Mumler Process, by way of his usual tinkering, in the same spirit of experimentation that produced his first ghostly picture.

Mumler died in 1884 after a short illness. An obituary in the Photographic Times was largely concerned with his “inventive genius” and “wide reputation as a photograph publisher” as the founder of Photo-Electrotype Company. His far more infamous origins were relegated to a pithy coda: “The deceased at one time gained considerable notoriety in connection with spirit photographs.”

What inspired Mary Cassatt’s portraits of mothers? Why did Jackson Pollock paint on the floor? Eureka investigates the origins of artists’ most famous works and techniques, unpacking how great art ideas happen.