Art World

Here’s Everything ‘The Undoing’ Director Susanne Bier Told Us About Art’s Prominent Role in Her Twisted HBO Drama

She described filming at the Frick Collection as “incredibly joyous.”

She described filming at the Frick Collection as “incredibly joyous.”

Katie Rothstein

This fall, HBO blessed art-history nerds and luxurious coat lovers alike with a gift for the eyes: Nicole Kidman playing a tortured and extraordinarily well-dressed mom on one of the most art-filled TV sets of the year.

The Undoing follows the story of Grace Fraser (Kidman), her husband, Jonathan (Hugh Grant), and her father, Franklin (Donald Sutherland), as they navigate the fallout from a violent murder in their Upper East Side private school community. While the big question at the heart of the whodunit was answered in the miniseries’s finale on Sunday, some viewers (also known as us) were left hungry for more information—about the art that decks the walls of the New York apartments shown on screen.

Susanne Bier, Nicole Kidman and Hugh Grant of The Undoing appear onstage during the HBO segment of the 2020 Winter Television Critics Association Press Tour. (Photo by Jeff Kravitz/Getty Images for WarnerMedia)

Enter Susanne Bier, who served as director and executive producer for the show. Besides being an Emmy, Golden Globe, and Academy Award winner, she also has a background in set design and architecture. The aesthetic of The Undoing was shaped in large part by her creative vision. “I love all the artists who are sort of touching upon the madness of being a human being,” she tells Artnet News.

Read on for Bier’s take on all the art in the show, from filming at the Frick Collection to that portrait of Kidman.

Grace Fraser (Nicole Kidman) at the home of the Spencers.

In the very first episode, Grace, Jonathan, and Franklin attend a school fundraiser at the home of the ultra-wealthy Spencers, who supposedly have two much talked-about works by David Hockney in their dining room. While viewers never actually see the Hockneys (some works are just too difficult to license), the apartment is filled with a lot of other bright, expensive-looking contemporary art. The Spencers’ grand collection, Bier says, is meant to contrast with the artwork later shown in Franklin’s apartment, which includes less showy (but still, of course, very expensive) Impressionist and Modern art.

“Obviously, it does sort of signal wealth, but I also felt that there was a huge difference,” Bier says of the two collections. “I mean, I love Hockney, but I do think that Franklin’s collection was kind of more personally curated. The home of the Spencers is super expensive, but also might be organized by interior decorators, while you felt that Franklin had probably bought his art himself.”

Inside Franklin’s apartment, with works by Turner, de Kooning, and Richter visible. Courtesy of HBO.

In order to create the sense that Franklin had assembled his collection personally over a long period of time, Bier’s team sought out works by famous artists that were uncharacteristic or little-known.

Franklin’s collection includes reproductions of Willem de Kooning’s Door to the River (1960), Diego Rivera’s Zapatista Landscape (1915), Henri Rousseau’s The Repast of the Lion (ca. 1907), and Juan Gris’s The Open Window (1921). This approach also had the added bonus of keeping realism intact, since most of the selected works were not particularly identifiable parts of major museum collections. “We’d never get away with pretending we have Guernica,” Bier notes.

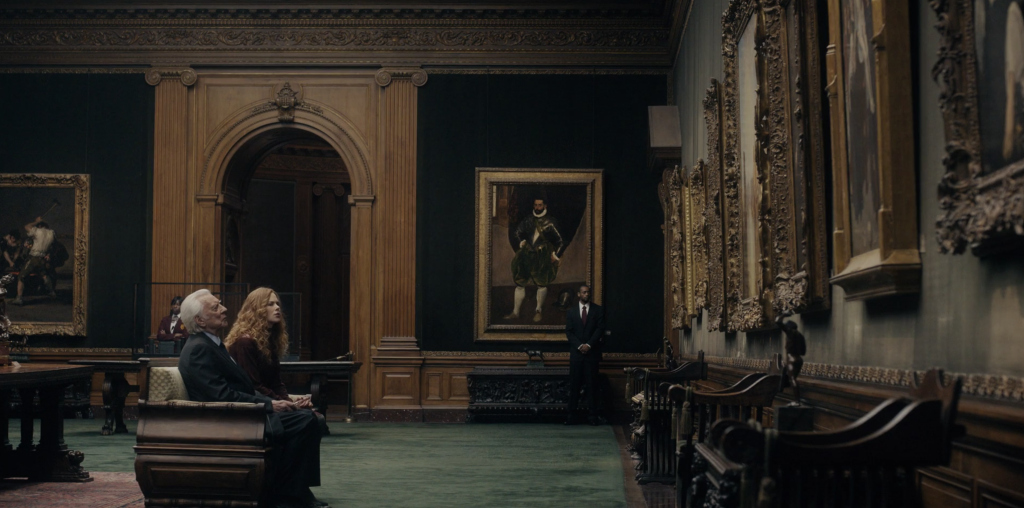

Donald Sutherland and Nicole Kidman at the Frick Collection in HBO’s The Undoing.

Some of the show’s most haunting scenes were filmed at the Frick Collection on the Upper East Side. Although they were not originally written with the Frick in mind, Bier realized that placing Franklin there added a layer of depth to his character and showed that he had a real love for art. Using a limited amount of equipment and a small crew on a day when the museum was closed, Bier described filming there as “incredibly joyous.”

At the Frick, Franklin sits in front of two different works by J.M.W. Turner: Harbor of Dieppe: Changement de Domicile (1826) and Cologne, the Arrival of a Packet-Boat: Evening (1826). “I like one more than the other, so he sits more in front of the one,” Bier said with a laugh. Another work by Turner, The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 16 October 1834 (1835), hangs in Franklin’s living room.

“I felt that Turner was right for him, because it’s magical, but it’s not about people, it’s about atmosphere,” Bier says. “They are the kind of paintings that you can keep looking at.” Plus, she adds, “it’s the closest to a landscape you get in a big city, so that was also part of it.”

Artist Lily Morris’s portrait of Nicole Kidman as Grace Fraser, as seen on the show.

In the fourth episode, detectives tell Grace that the murder victim Elena Alves (Matilda De Angelis), a fellow mom at the school Grace’s son attends who is also a practicing artist, made an extremely detailed painting of Grace before she was killed.

“I think it probably was something [series writer] David [E. Kelley] invented,” Bier says of the idea to include the portrait in the script. Although the portrait is shown to the audience only in an iPhone photo, it turns out the real painting was made by artist Lily Morris, whose work was also featured in Bier’s last project, Netflix’s Bird Box (2018). (Morris created the paintings that filled the studio of the film’s protagonist, played by Sandra Bullock.)

For her part, Morris recounts that Bier called her out of the blue one day and asked her to make a portrait of Nicole Kidman “immediately.” She enthusiastically obliged. In subsequent conversations, the pair discussed how to depict someone “who was the object of someone’s obsession.”

“It just so happens that Nicole Kidman naturally embodies so many of the exaggeratedly majestic qualities obsession tends to generate,” Morris says.

It’s no wonder Bier so cannily incorporates art into her productions. Morris says the director shares with visual artists a common interest in capturing the human psyche.

“Susanne is the ultimate observer of human nature,” Morris notes. “She glides into every situation, observes, inhales the nuances of human behavior, and then translates them to the screen.”