Archaeology & History

A Remarkably Preserved 1,900-Year-Old Dolphin Mosaic Is Unearthed in England

Wroxeter, the fourth-largest town in Roman Britain, has turned up a rare find.

Wroxeter, the fourth-largest town in Roman Britain, has turned up a rare find.

Vittoria Benzine

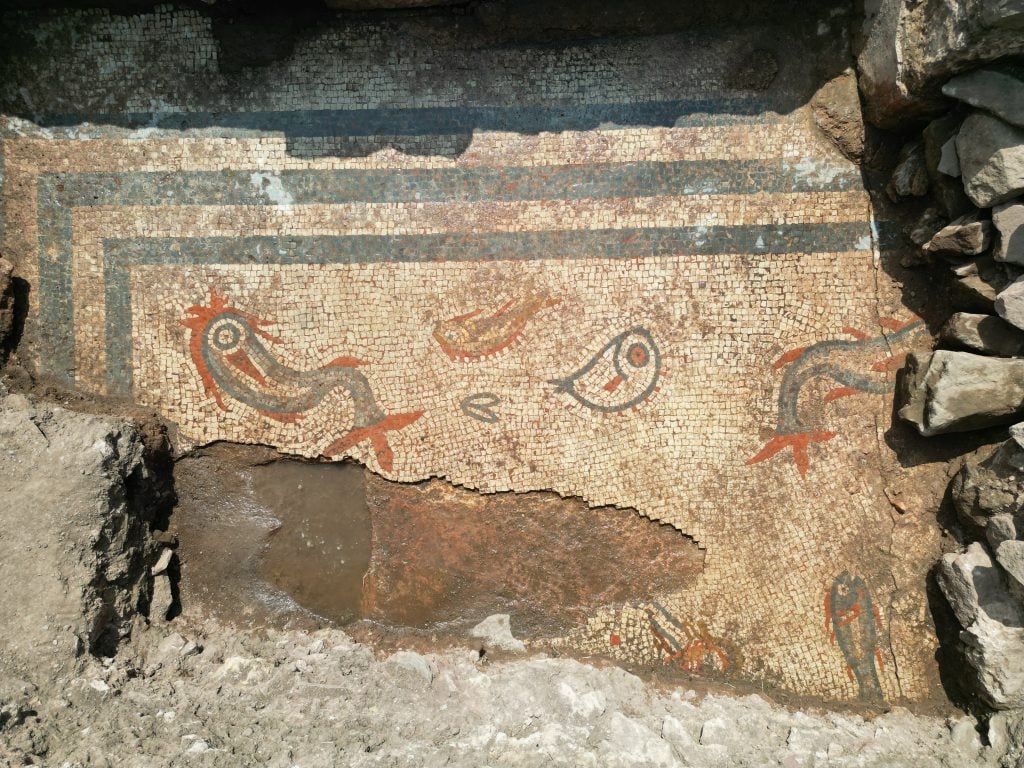

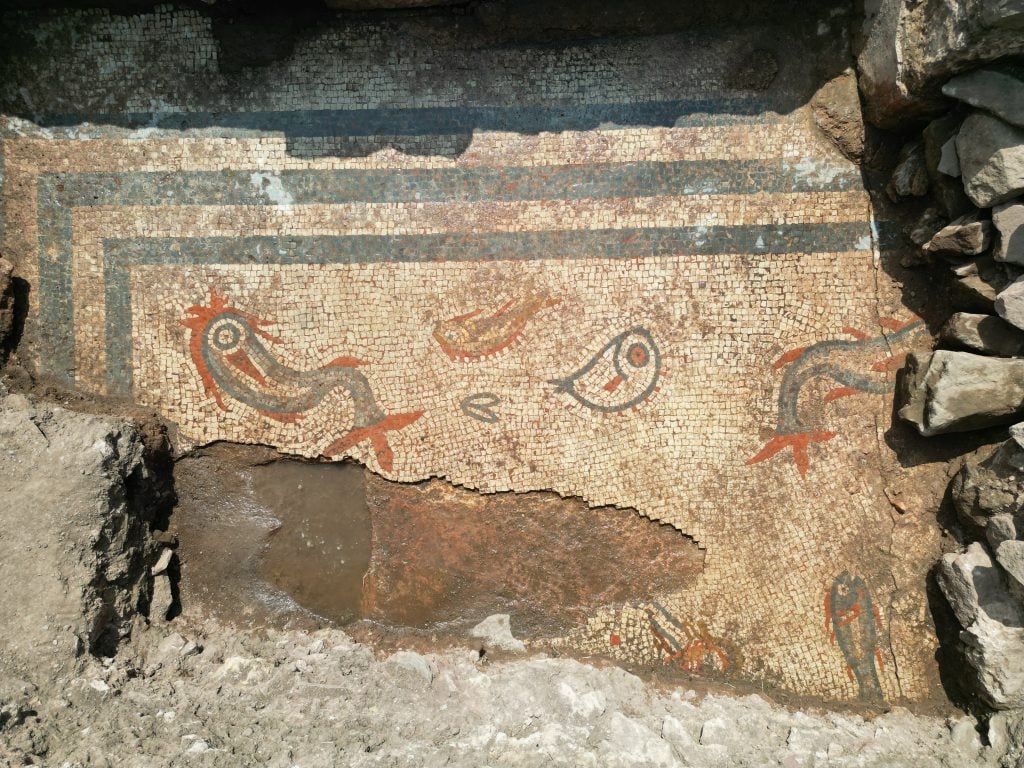

A group of archaeologists, students, and volunteers from four British organizations announced the discovery of a stunning mosaic depicting dolphins in the ruins of the Roman city of Wroxeter, near Shropshire, in central England. The 1,900-year-old treasure depicts marine creatures in brilliantly preserved red and blue tiles against a yellow background with blue borders. English Heritage, which administers the site, surmises that a high-ranking individual in the once-bustling Roman city commissioned the mosaic for their townhome.

The Roman empire first established Wroxeter (Viroconium Cornoviorum in Latin) as a military outpost after conquering England’s western midlands in 43 C.E. By the end of the century, Wroxeter had become the fourth-largest town in Roman Britain—comparable to Pompeii—with 200 houses, a town hall, and awe-inspiring bathhouses where residents could maintain strict Roman beauty standards.

Wroxeter flourished until the mid-5th century. The city’s remote location has helped preserve it. A small number of ruins, like the Old Work—the U.K.’s largest freestanding Roman wall—still stand today. But, while experts have been excavating Wroxeter since its discovery in 1859, most of the metropolis is yet to be unearthed.

Wroxeter. Courtesy of English Heritage

Wroxeter’s latest treasure turned up during excavations that opened new trenches north of the city’s forum. These efforts aimed to unearth its main civic temple after geophysical surveys revealed a walled precinct buried under the area.

“As hoped, the excavation uncovered a large, monumental building along the city’s main road, as well as uncovering a shrine or mausoleum within the precinct which may have honored an important individual in Wroxeter’s earliest history,” says English Heritage. “Possibly someone associated with the legionary fortress or perhaps a founding father of the new city.”

The dig also turned up smaller loot like pottery, building materials, and coins. These relics, mainly dated to the 4th century, help map Wroxeter’s history. The mosaic, on the other hand, likely dates to the early 2nd century, and is accompanied by the remnants of a painted plaster wall, standing at knee height.

Students cleaning the newfound dolphin mosaic. ©Vianova Archaeology

“It is extremely rare to find both a mosaic and its associated wall plaster, and nothing like it has ever been found at Wroxeter,” remarked the University of Birmingham’s Roger White, who co-directed the four-week dig. White also noted that Wroxeter “offers scientific opportunities to understand how the Roman city became productive farmland for more than 1,500 years following its demise,” which “may offer insights into the future evolution of the soil in the light of climate change.”

Dolphins, meanwhile, frequently feature in Greek and Roman art—often symbolizing romance and sea travel. Regarding the Wroxeter dolphin mosaic, however, English Heritage archaeologist Win Scutt said via email, “I don’t think they were meant to symbolize anything.” Instead, Scutt said, this bespoke mosaic “demonstrated the wealth, taste, and prestige of the owner, who must have been an important person living so close to the forum, basilica, and baths.”

The mosaic has since been reburied for its own protection. Wroxeter’s main civic temple remains at large.