On View

A Centuries-Spanning Exhibition Investigates the Age-Old Lure of Money

The Morgan's Medieval manuscripts feature prominently in the exhibition.

The Morgan's Medieval manuscripts feature prominently in the exhibition.

Richard Whiddington

Three miles north of the Manhattan court room where Sam Bankman-Fried went on trial, a very different investigation into the nature of money is taking place—the setting is the Morgan Library & Museum and the examination in question is an exhibition into the rise of the monetary economy in Medieval Europe. The centralized systems that FTX rebelled against were, in some ways, born in the 12th and 13th centuries as agricultural advancements—helped by an ecological “warm period” during the Middle Ages—and expanding trade routes that brought an economic revolution to the continent.

Banks were established in Spain, Northern Europe, and the Italian city-states to facilitate increasingly complex and widespread financial transactions. Coin production duly boomed, a fact apparent in the first display visitors encounter at “Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality”: a dull pile of low-value coins, the likes of which were minted in high volume to lubricate the economy.

Coins from the Chalkis hoard in Greece, late 14th century. Photo: courtesy of American Numismatic Society, New York.

“Previously mints produced few coins and these were of high value. This situation couldn’t sustain growth at all levels of the economy,” said exhibition curator Diane Wolfthal. “After the year 1100, more coins, including lower-value coins, began to be produced, which were essential for market penetration into the everyday life of ordinary people.”

As money flowed into every facet of Medieval life, uplifting some and indebting others, it brought forth a litany of ethical complications. Chief among these was the quandary over how to pursue wealth and yet lead a good Christian life. Fitting then that the former personal library of J. Pierpont Morgan should play host to such questions.

The American banking giant was a devout Episcopalian and, if the 16th-century tapestry that still hangs over his East Room is anything to go by, he may have grappled with the inherent corruptions of wealth. Triumph of Avarice, designed by Netherlandish artist Pieter Coecke van Aelst, shows the personification of the deadly sin riding out of Hell and past the corpses of the gluttonous.

Triumph of Avarice, Willem de Pannemaker ca. 1534-1536. Photo: courtesy The Morgan Library & Museum.

Elsewhere, Hieronymus Bosch chimes in through Death and the Miser, a work on loan from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. It is, as ever, a work of anguish, trickery, and—to modern eyes at least—searing wit. Death slips a slender ankle across the threshold and tempts a dying man to ignore the angel lingering at his shoulder. Will he choose the gold in his strongbox or turn to God? Bosch leaves the decision to the viewer.

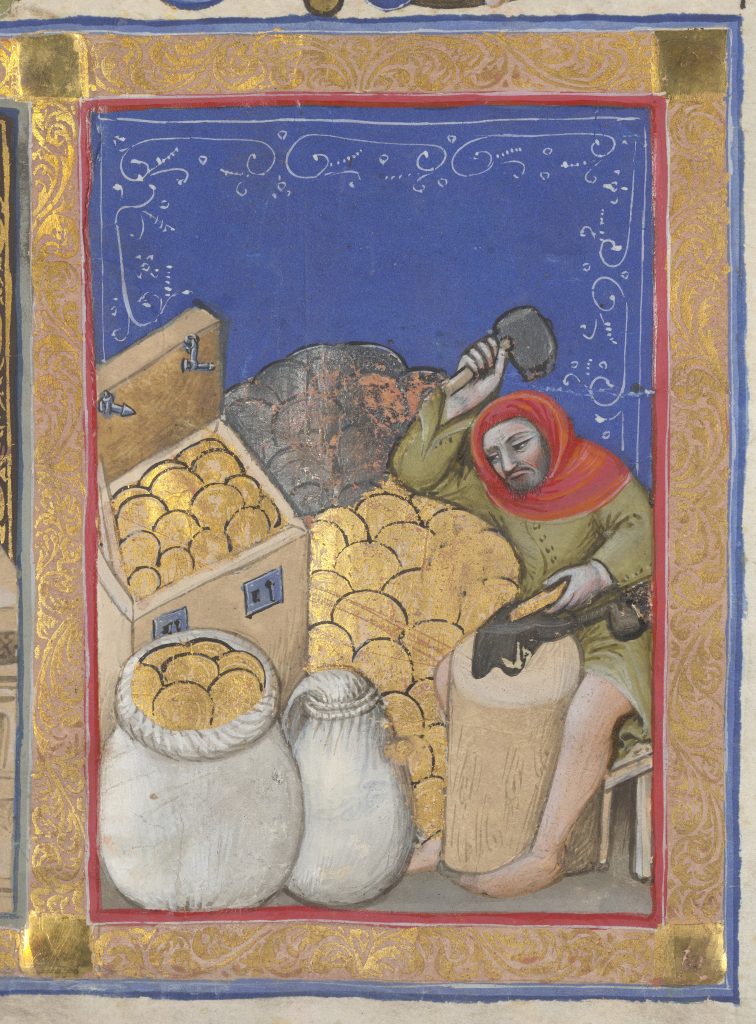

Characteristically, works from Morgan’s collection ground the exhibition, which runs through March 10. There’s a register frontispiece from a Bologna lending society that shows a goldsmith at work in a room swirling with the precious metal. A kindly Hans Memling portrait of an Italian merchant holding a pink flower serves as a clear, if obvious, reminder that the Northern Renaissance was largely funded by a class of newly minted merchants.

Hieronymus Bosch, Death and the Miser (ca. 1485–90). Image: courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Most notable, however, are the Medieval manuscripts, of which Morgan was a greedy collector. Together, they show how money slipped into seemingly every aspect of Medieval life. It made financial planning possible, as shown in a 16th-century calendar commissioned by royal chamberlain Philibert de Clermont, which recommends men to begin gathering their retirement resources at the age of 48.

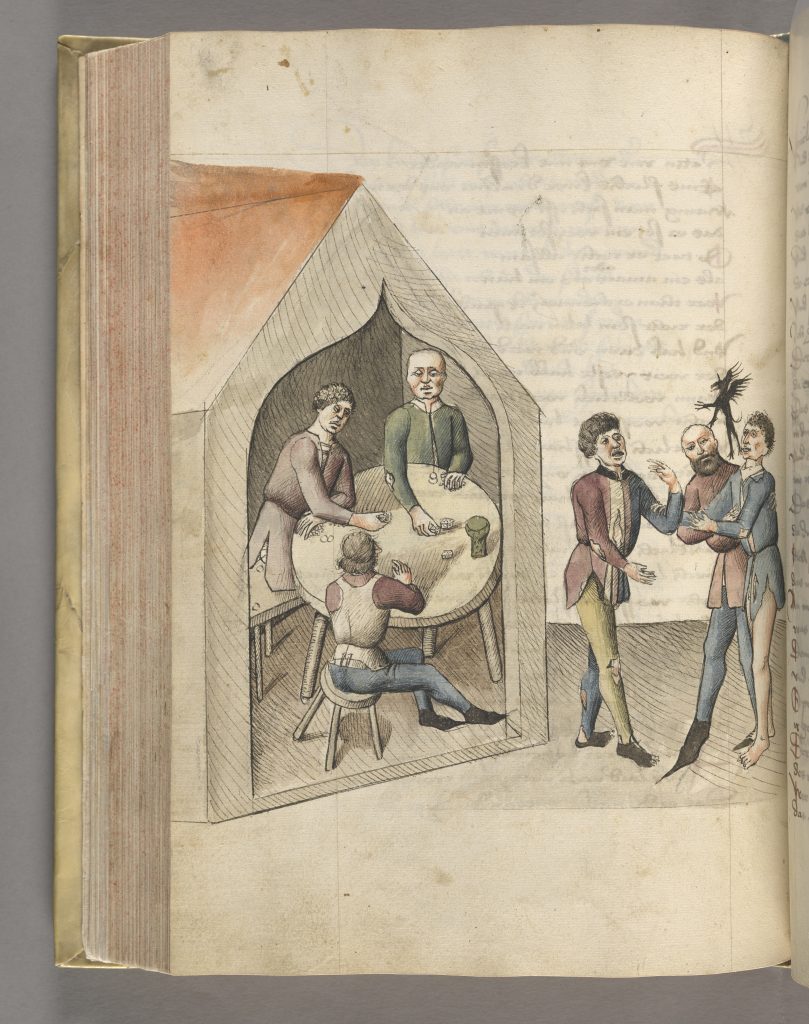

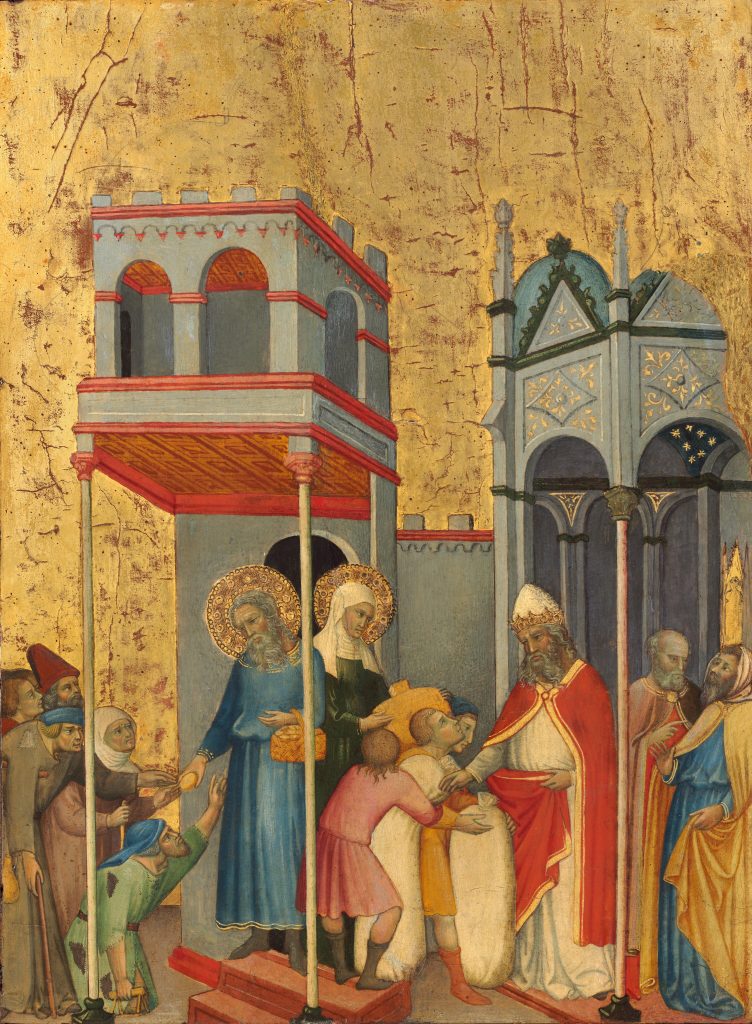

It fueled urban vice and gambling, presented in the illustration of an epic German poem on sin showing three criminals huddled around a dice game. It deepened social inequalities which prompted the church to act as a financial benefactor to the poor and give alms, as depicted in the prayer book of Queen Claude of France.

Gerard of Villamagna Soliciting Alms for the Poor, from Vita Christi (Life of Christ). Illuminated by Pacino di Bonaguida and workshop Italy, Florence, ca. 1300–25. Image: courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum.

Although concerns of money’s corrupting power became more pressing in this period, they weren’t, of course, entirely new. There were lessons aplenty in the Bible with the virtues of frugality preached by Jesus, St. Francis, and St. Antony, all of whom are portrayed at the Morgan.

It’s a reminder not of a simpler time, but rather of a world gripped by the same questions and stereotypes as today. Take the stigmatization of Jews, Wolfhal says, or the categorization of poor people as undeserving, or religious narratives used to justify the extraordinary wealth of a few (think of today’s prosperity theology or indeed effective altruism).

“I hope visitors will see how complex Medieval discussions of money were, and think about the role money plays in their own lives,” Wolfhal said. “We have much to learn from the Medieval past.”

See more images from the exhibition below.

Frontispiece from a register of creditors of a Bolognese lending society Illuminated by Nicolò di Giacomo di Nascimbene (ca. 1394–95). Image: courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum.

Hans Memling, Portrait of a Man with a Pink (ca. 1475). Image: courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum.

Hugo von Trimberg Der Renner (The Runner), Gamblers and Criminals (1476–99). Image: courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum.

Andrea di Bartolo, Joachim and Anna Giving Food to the Poor and Offerings to the Temple, Sienna (ca. 1400–05). Image: courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Der Rychman (The Rich Man) (1523–26, published 1538). Image: courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

More Trending Stories:

Conservators Find a ‘Monstrous Figure’ Hidden in an 18th-Century Joshua Reynolds Painting

A First-Class Dinner Menu Salvaged From the Titanic Makes Waves at Auction

The Louvre Seeks Donations to Stop an American Museum From Acquiring a French Masterpiece

Meet the Woman Behind ‘Weird Medieval Guys,’ the Internet Hit Mining Odd Art From the Middle Ages

A Golden Rothko Shines at Christie’s as Passion for Abstract Expressionism Endures

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

Mega Collector Joseph Lau Shoots Down Rumors That His Wife Lost Him Billions in Bad Investments