Basel is proud of its Picassos. Two paintings in particular occupy a special place on the walls of the Kunstmuseum Basel. How they were purchased with public money, and prompted the artist to donate four works, and a donor another, to the permanent collection in one year reads like an art-world fable.

The exhibition “Art. Money. Museum: The Picasso Story, 50 Years Later,” which opens this week, aims to do more than retell the story of their extraordinary acquisitions in 1967. The show raises existential questions about the value of art in public collections as the cost of masterworks heads beyond the reach of most museums.

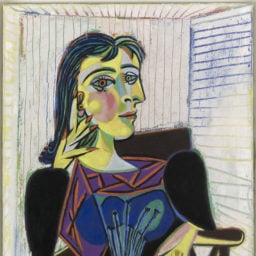

Once upon a time, Basel was shocked to discover that two of “its” great paintings by Picasso, The Two Brothers (1906) and Seated Harlequin (1923) had only been on loan and were about to be sold. The heirs of the collector and entrepreneur, Rudolf Staechelin, agreed to give the Kunstmuseum Basel first refusal but the city need to raise around CHF 8.4 million ($9 million).

The hero of the tale is the museum’s director, Franz Meyer, who turned a crisis into a golden opportunity.

The decision went to a public vote. Public opinion was divided but the fear that the paintings might end up in America focused people’s minds. “Some people said [the city] should build nursing homes,” with the money, says the exhibition’s curator, Eva Reifert. “Some artists thought it should be spent on building a museum of contemporary art.” Other artists said a vote to buy the Picassos was a vote in favor of art, so backed their purchase. “Everyone was surprised when the referendum vote was a ‘yes,’” she says. Around CHF 6 million ($6.4 million) came from the public purse, and the rest was raised by a day of fundraising, nicknamed the Bettlerfest (beggar’s feast).

When Picasso heard the news, he was impressed. Touched by the vote in confidence in his art, he offered four works as a gift. Picasso decided on Man, Woman and Child (1906) and a sketch for the Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), He invited Meyer to Mougins choose two new works for Basel. Meyer picked two great late paintings: Venus and Cupid and The Couple (1967). Completing Basel’s miraculous year, Maja Sacher-Stehlin donated Picasso’s 1912 Cubist painting The Poet to make the total seven.

The exhibition aims to strip away the sugar-coating of the oft-told story on the 50th anniversary of the works going on show. (The museum hung out a banner proclaiming “The Picassos Are Here!) “We want to dust off all the embellishments and the ‘miracle’ stuff,” she says, stressing it was a hard-fought debate and a close-run thing. The turn out was 39%; 32,118 people voted yes, and 27,190 voted no.

To bring the issues up to date, the Kunstmuseum Basel’s current director Josef Helfenstein, formerly the head of the Menil Collection in Houston, debates the issue raised in a dramatized audio-visual “conversation” with Meyer. Helfenstein stresses that a museum cannot depend on loans from private collectors that one day might be taken away. “That would be living in the moment,” Reifert says, adding that it merely “makes the museum look good.” Only gifts—and purchases—are forever. The moral of the story is that where there’s a will, there’s a way to unlock public money and private generosity.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Culmination (2016), courtesy of the artist; Corvi-Mora, London, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

To bring the tale up to date, the exhibition includes acquisitions made over the past 50 years, many installed as if on museum storage racks. These include a recent star acquistion, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s A Culmination (2016). The British artist’s large-scale group portrait was acquired after her solo show “A Passion to a Principle” at the Kunsthalle Basel in 2016-17.

Kunstmuseum Basel, “Art. Money. Museum: The Picasso Story, 50 Years Later,” March 10 – August 12, 2018.