People

Remembering Faith Ringgold and Her Rich Tapestry of the Black Experience

The artist has died at 93.

The artist has died at 93.

Vittoria Benzine

To revere Faith Ringgold’s work is to revere Faith Ringgold herself. The artist said as much when she affirmed that essentially all of her work is autobiographical in 2022. Her first story quilt, for instance, included pieces of the autobiography she was then struggling to get published.

On Saturday, April 13, ACA Galleries announced that the artist, author, educator, and organizer passed away in her Englewood home at age 93. Tributes and remembrances poured in on social media, honoring Ringgold’s diverse practice and singular spirit.

Faith Ringgold, Street Story Quilt (1985). Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund and funds from various donors 1990.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, who curated her first European institutional survey at Serpentine Gallery in 2019, posted both a video and handwritten note in which Ringgold remarked that anyone can fly. The mention of flight alludes not only to her first story quilt Tar Beach (1988), which she turned into an acclaimed children’s book three years later, but also the mission of the Anyone Can Fly Foundation, which she established 1999 “to expand the art establishment’s canon” by promoting and supporting Black artists throughout the diaspora.

“As for my own legacy?” she is quoted in a post that Harper’s Bazaar editor-in-chief Samira Nassar shared, featuring the artist’s portrait as shot by John Edmonds. “I hope my work expresses the life and deeds of Black people, and other aspects of the world that have thrilled me.” Curator and writer Enuma Okoro recounted an interview she conducted with the artist during her celebrated New Museum retrospective in 2022, when Ringgold beamed and remarked: “I’m so happy that I went ahead and did this because so many artists stop, or don’t fulfill their dream.”

Faith Ringgold, Tar Beach II (1990). ©Faith Ringgold/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Ringgold was born October 8, 1930 in Harlem, New York, where her parents Willie Posey Jones and Andrew Louis Jones landed during the Great Migration. Ringgold’s father, a truck driver, left when she was two, but remained in close contact. Her mother was a sought-after fashion designer and seamstress who was so successful that she moved Ringgold and her two older siblings to the prestigious Sugar Hill enclave. There, Ringgold grew up playing with fledgling saxophonist Sonny Rollins while watching the limos of Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes roll by.

In 1948, Ringgold began studying at City College, where she was forced to major in art education rather than art alone because she was a woman. After 10 years, a marriage, two children, and a divorce, Ringgold earned her Masters degree from the same school. The artist brought her mother and her kids on a trip to Europe after, where they visited museums from Paris to Rome—a trip that would prove inspirational for her later series, “The French Collection” (1991–97). The following year, she married Burdette Ringgold; the two remained together until his death in 2020.

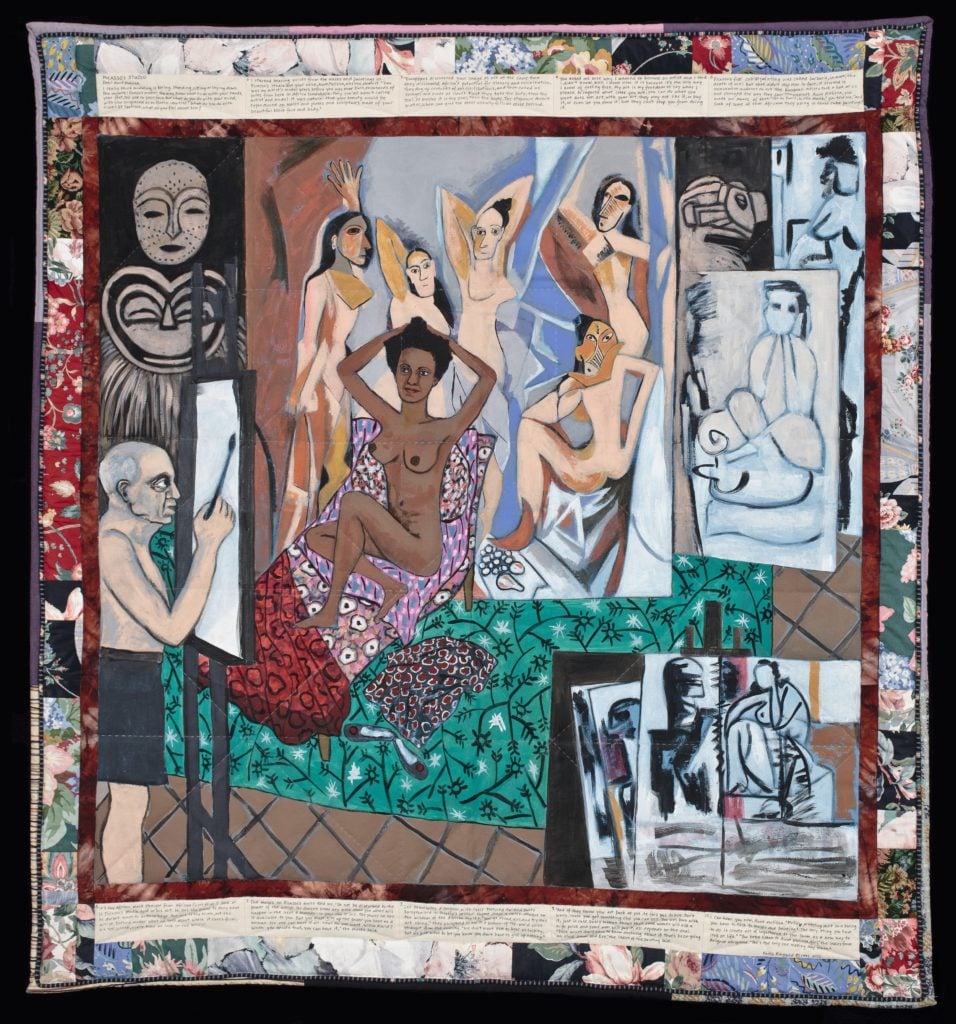

Faith Ringgold, Picasso’s Studio (1991). © 2020 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York.

Of all the white, male artists Ringgold had to copy throughout art school, Picasso proved her favorite. While teaching art at New York public schools during the 1960s, she produced oil paintings that paired Cubism with her own love for the African masks that had inspired Picasso—and drew on observations of cultural unrest for subject matter.

In 1967, 500 guests attended the opening of her debut solo show “American People” at Spectrum Gallery, including Romare Bearden and Richard Mayhew. The series encapsulates America’s racial, gender, and class-related tensions of the 1960s through the mod aesthetics and snappy symbology of the era’s mass media boom. Most scenes are gruesome and incendiary, and provoked backlash. Today, #20: Die hangs by Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon at the MoMA.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #18: The Flag Is Bleeding (1967). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund and Gift of Glenstone Foundation (2021.28.1). © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022

In her 1995 memoir We Flew Over the Bridge, Ringgold detailed her realization of a disparity between the Western canon’s focus on white through shadow and light versus African art’s tendency to use colors over tones in denoting forms. She therefore sought “an affirmative Black aesthetic.”

In 1972, her students’ spirit of exploration and the brocade-framed thangka scroll paintings she saw at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum—along with her family’s long quilting lineage—inspired her Slave Rape series, the textiles framing tales of enslaved women rendered in acrylic paint, as well as soft sculptures Ringgold made, such as a doll inspired by Wilt Chamberlain’s memoir. Ringgold and her mother also fashioned African masks of fabric, beads, and raffia. Some appeared in her performances, like The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro (1976).

Jan van Raay, Faith Ringgold (right) and Michele Wallace (middle) at Art Workers Coalition Protest, Whitney Museum (1971). Courtesy of Jan van Raay, Portland, OR, 305-37. © Jan van Raay

Ringgold didn’t operate in isolation. She lectured extensively, formed cohorts for Black female artists, protested to get Black artists and women in museums, and even designed posters for the Black Panther Party. After traveling West Africa, Ringgold and her mother created her first quilt, Echoes of Harlem (1980).

“My quilts are really paintings,” she once said, contrasting these wall-hanging works with the utilitarian objects her enslaved forebears were forced to make. “They’re acrylic on canvas with a pieced fabric border, so they’re paintings that are unstretched, with quilted frames.” Those quilts featured even more detailed narratives in the years following her mother’s death, beginning with the groundbreaking Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983), a piece that imagined a rich life for the Black female stereotype.

Faith Ringgold in her studio at her home in Englewood, NJ, 2013. Photo: Melanie Burford/Prime for The Washington Post via Getty Images.

In her latter-day career, Ringgold’s reach grew alongside an increasing number of retrospectives from a 1984 show at the Studio Museum to a major survey at the Serpentine Galleries in 2019. The many children’s books she began writing and illustrating in the 1990s—about her Harlem childhood, and such figures as Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks—further expanded her lifelong mission to elevate and celebrate Black identity.

“I only do art about things that I know and feel and am concerned with,” she said in 2022. “I don’t divorce my art from myself.”