Archaeology & History

Amber Was So Coveted 5,000 Years Ago, People Made Fake Versions of It

Amber was a symbol of luxury, even in prehistoric times.

In Steven Spielberg’s classic film Jurassic Park, scientists use DNA from a prehistoric mosquito preserved in amber to clone dinosaurs, bringing the long-dead creatures back to life.

People have been fascinated by amber for millennia. Long before we understood how it was created, the shiny, mesmerizing material was a symbol of wealth, processed into beads, jewelry, and other fashion accessories. As shown by a new study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, it was so coveted that, in places where it was scarce, recipes for faux, imitation amber emerged to meet rising demand.

Amber beaded jewellery. Dated 3th Century BC (Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Amber, in case you didn’t pay attention during biology class (or Jurassic Park) is essentially fossilized tree resin, formed over a minimum of 40,000 years. Many vascular plants around the world secrete resin from the dense inner part of their trunks to protect themselves from infections and wounds caused by insects or exposure to the elements.

For centuries, amber’s origin remained a mystery. Demostratus, an Athenian orator from the 2nd century BC, referred to the material as lyncurium, as it was commonly believed to originate from the urine of lynxes—a belief that persisted into the early Middle Ages, depicted in illuminated manuscripts.

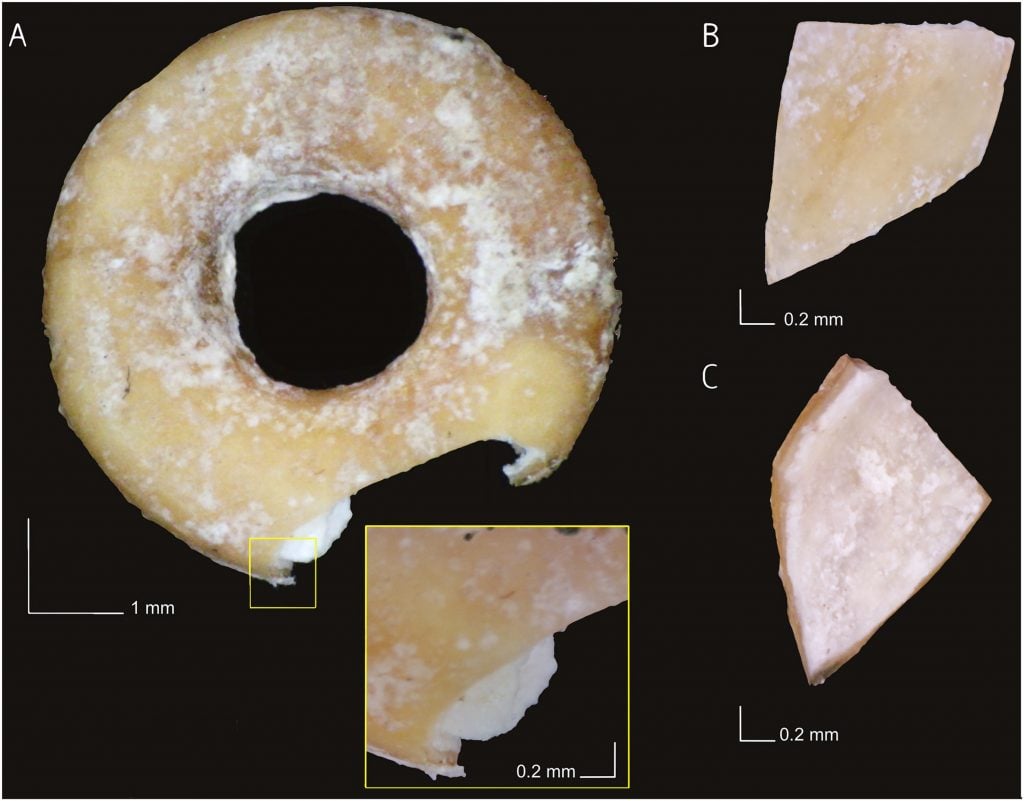

Coated resin beads recorded and analyzed in this work. Photo: Carlos P. Odriozola et al. / Journal of Archaeological Science.

Thales of Miletus, a natural philosopher who lived during the 6th century BC, was surprised to learn that, when rubbed against a piece of cloth or animal fur, amber would attract lightweight objects like feathers. In his text Natural Faculties, the Greco-Roman physician Galen, too, noted the material’s magnetic properties.

At various points in history, people believed that amber came into being when rays of sunlight touched the surface of the sea, that it possessed magical qualities capable of curing madness and infertility, and that it was a token of a good fortune.

Above all, amber’s shiny, translucent consistency and warm, orang-y color made it a popular material for jewelry. Amber earrings, necklaces, and charms have been found all across the world, including in places where the material did not naturally occur, such as the Iberian peninsula. Upon closer inspection, amber beads recovered from this area—made between the 5th and 2nd millennia BC—turned out to be faux amber, made from non-fossilized pine resin, beeswax, and linseed oil, joined together with a glue of boiled collagen, or bone.

Close-up of one of the faux-amber beads analyzed in the study. Photo: Carlos P. Odriozola et al. / Journal of Archaeological Science.

According to Carlos Odriozola, a professor at the Department of Prehistory and Archeology at the University of Seville, and co-author of the study, these imitation beads featured “a pattern that was repeated from one end of the peninsula to the other and maintained for a millennium.” As such, the researchers believe that amber forgery must have been more common than previously thought.

Left, real amber beads 6th-5th century B.C. Photo: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images. Right: Close-up of one of the faux-amber beads analyzed in the study. Photo: Carlos P. Odriozola et al. / Journal of Archaeological Science.

The quantity and geographic distribution of the beads suggests the existence of a complex social structure, complete with specialized crafts and wealth disparities. “It was a time in history when appearance began to be very important,” another co-author, José Ángel Garrido, also from the University of Seville, told Spanish newspaper El País.

“It follows the same logic as someone who drives a Ferrari on the street today,” Odriozola added.