On View

Debates About How to Interpret Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Art Are Raging. A New Show Is Proposing a Fresh Way of Reading It

The exhibition at David Zwirner comes with instructions outlining the "core tenets" of the artist's installations.

The exhibition at David Zwirner comes with instructions outlining the "core tenets" of the artist's installations.

Taylor Dafoe

Last fall, a few astute visitors to the Art Institute of Chicago noticed that the museum had quietly swapped out the wall text for Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s 1991 artwork Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.). Whereas a previous placard alluded to the artist’s late partner, Ross Laycock, who died from an AIDS-related illness the same year the piece was created, the new signage simply describes Untitled’s conceptual framework.

“The erasure of Ross’s memory and Gonzalez-Torres’s intent in the new description is an unconsciable [sic] and banal evil,” read one Twitter user’s post, which was reshared on the platform thousands of times. Others online soon decried the museum’s supposed act of “erasure,” too, and some even postulated that it was part of a larger effort on the part of Gonzalez-Torres’s foundation to distance the late artist’s biography from his work.

“There’s no obliterating Felix’s biography. [There’s] no desire to, no reason to,” said Andrea Rosen, president of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, when asked about the incident in a recent interview. Near the Art Institute’s label for Untitled, she pointed out, is a QR code that directs viewers to an audio guide describing the work’s connection to Laycock and the context of the AIDS epidemic.

Rosen was clearly rankled by the accusations of erasure. That she would feel that way makes sense: A former dealer, Rosen hosted one of Gonzalez-Torres’s first solo shows in 1990, and continued to represent him up to and beyond his death in 1996 from AIDS-related illness. For three decades now, she has been the foremost promoter of his work; their accomplishments are inseparable. (Rosen now co-represents the artist’s estate with David Zwirner.)

Still, she managed to find a silver lining. “It is crazy how Felix’s work continues to generate such meaningful and complex dialogue,” Rosen said. “Thank god!”

Installation view of “Felix Gonzalez-Torres” at David Zwirner, New York, January 12 – February 25, 2023. Courtesy of David Zwirner.

Indeed, what the incident at the Art Institute illustrated was the complexities and nuances inherent to Gonzalez-Torres’s work—and the intense personal connection to his story that many feel.

Those upset by the eliding of Laycock and AIDS from the museum’s wall label weren’t wrong. That’s the thing about Gonzalez-Torres’s work: It allows, even encourages, different emotional reactions. From his poetic billboards to his piles of candy, no artist was better at generating conceptual prompts that felt both personal and universal, both specific enough to grab you and open-ended enough for myriad points of entry.

Now, on the occasion of Gonzalez-Torres’s new exhibition at David Zwirner, where two installations conceived by Gonzalez-Torres have been realized for the first time, Rosen and the rest of her team are again thinking about the unique interpretability of the artist’s output. The show marks the formal introduction of the Foundation’s new Core Tenets—that is, a series of documents that outline the conceptual parameters of Gonzalez-Torres’s artworks.

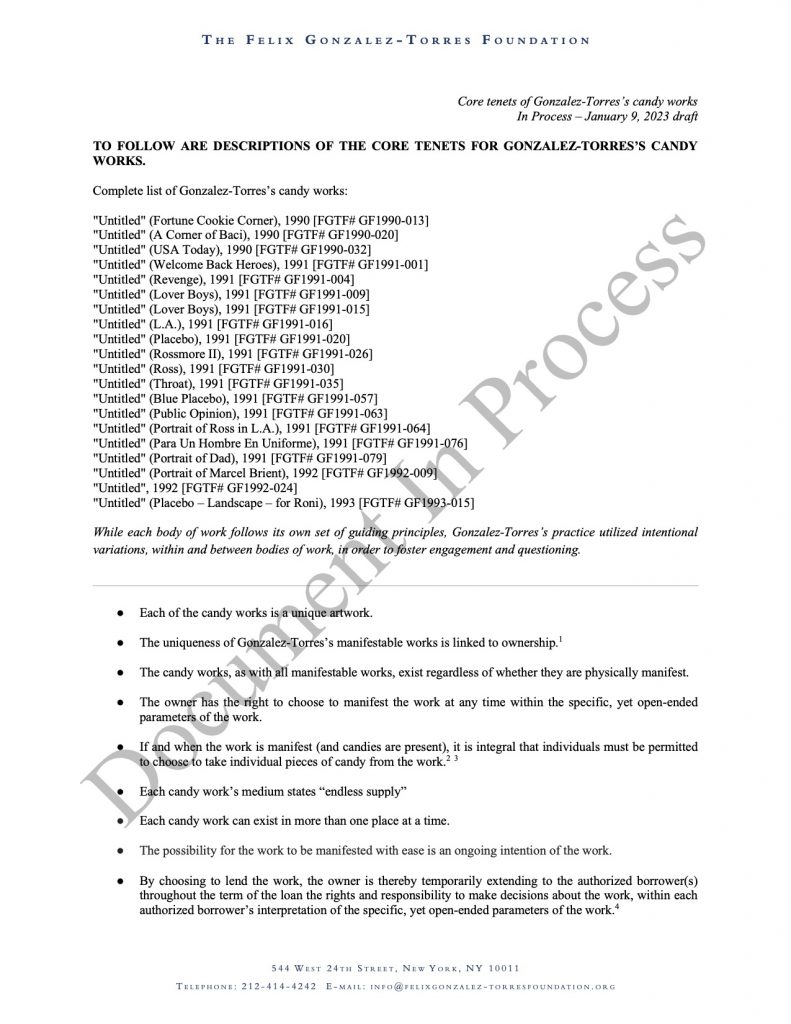

Through Zwirner’s website, gallery-goers are provided with sheets of paper that look, at first glance, like contracts. That is what they are, in a way—contracts that define the rules of works on display, based on language from the artist himself.

“Each of the candy works is a unique artwork… The candy works, as with all manifestable works, exist regardless of whether they are physically manifest… The possibility for the work to be manifested with ease is an ongoing intention of the work,” reads some of the bulleted tenets for Gonzalez-Torres’s candy installations, one example of which (“Untitled” (Public Opinion) from 1991) is on view at Zwirner in two different parts of the gallery.

A page from the “Core tenets of Gonzalez-Torres’s candy works,” an in-process draft fromJanuary 9, 2023. Courtesy of David Zwirner.

Printed on foundation letterhead, the documents are dry and rather dense. Each catalogues the works to which the stated tenets apply (there are 20 iterations on the “Candy Works” document, including Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)), and boasts a list of postscript annotations long enough to make David Foster Wallace blush.

So authoritative are the tenets that they almost feel like a direct response to the Art Institute controversy. Viewed through that lens, it is as if the documents are saying, “No, this is how you read Gonzalez-Torres.”

But Rosen said that the project, which goes back years, is about doing the exact opposite. The idea, she explained, is to point to “what is stable within Felix’s work,” while also showing how individual installations fit within a broader corpus.

It’s a novel solution to the unique challenges of presenting and experiencing this particular artist’s creations. For those that already find Gonzalez-Torres too heady, the tenets may feel like more homework.

But then again, who really thinks that about him? The artist’s genius came through his ability to establish a set of conditions to which everyone—from academics to children copping a piece of candy—could relate on their own terms. To its credit, the Tenets project gets that people will bring to Gonzalez-Torres’s work the kind of intense attention that only comes through personal connection.

Installation view of “Felix Gonzalez-Torres” at David Zwirner, New York, January 12 – February 25, 2023. Courtesy of David Zwirner.

Rosen echoed this idea too, noting that the project “creates as much responsibility for people to understand the work as it does provide information.” Rosen went on, “It’s a way of becoming a kind of Felix thinker.”

And it’s not objectivity the foundation is after. In addition to the tenets, Rosen also commissioned a handful of writers and curators to reflect on their own, highly subjective relationships to Gonzalez-Torres’s art in a series of audio essays that are available on Zwirner’s website.

“The more subjectivity around Felix, the more diverse ideas around Felix—the better,” Rosen said.