People

Fernando Botero, Whose Robust, Sensual Style Belied a Sly Political Wit, Has Died

News of his passing was shared by Colombian president Gustavo Petro.

News of his passing was shared by Colombian president Gustavo Petro.

Taylor Dafoe

Fernando Botero, a world-renowned Colombian artist known for his bulbous figures and sensuous subject matter, died today in a Monaco hospital. He was 91.

The cause of death was complications from pneumonia, his daughter, Lina Botero, told the Bogotá-based radio station Caraco. The news was later confirmed on social media by Colombian president Gustavo Petro, who called the artist “the painter of our traditions and defects, the painter of our virtues.”

Across a seven-decade-long career, Bottero developed a style—sometimes referred to as “Boterismo”—that was unmistakably his own. His subjects, often middle-class laborers in moments of leisure or celebration, bore pinched facial features and plump frames. His depictions of food and land were similarly sumptuous. References to European art history shaped his painted scenes; so did a pair of competing impulses under the surface: humor and social critique.

“Nobody believes me, but it is true. What I paint are volumes,” he said in a 2014 interview. “I am interested in volume, the sensuality of form.”

Some critics dismissed his work as unserious or out-of-touch, but once established, the artist never lacked an audience. At the height of his career, Botero was one of the best-known—and wealthiest—artists in the world.

Fernando Botero, Three Women Drinking (2006). Courtesy of the Athenaeum.

Fernando Botero Angulo was born on April 19, 1932, in Medellín, the second of three sons. His father, a traveling salesman, died when he was four, leaving a vacuum later to be filled by his uncle. An early interest in bullfighting later gave way to a passion for the arts. By age 16, he was making illustrations for a local newspaper.

In 1951, the artist moved to Bogotá, where he had his first solo show, then to Madrid to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando. Stints in Paris and Florence came next as he soaked up the kind of canonical European art to which he lacked access growing up.

The artist married his first wife, Gloria Zea, during his travels. The duo returned to Bogotá in 1958 with three children: Fernando, Lina, and Juan Carlos. The pair divorced in 1960 and Botero moved to New York, where he began painting employing the kind of curvaceous forms that would soon become his signature.

In 1970, he had a son, Pedro, with his second wife, Cecilia Zambrano. The child died in a car accident in 1974—an event that would cast a pall over his work and personal life for years afterward. Later that decade, he started producing large-scale sculptures of his rotund figures, eventually installing examples in prominent locations around the world, such as New York’s Park Avenue and Medellín’s San Antonio Plaza.

The latter location, where Botero’s bronze Bird of Peace sculpture is installed, was targeted in a terrorist attack in 1995. Twenty-two pounds of dynamite left at the artwork’s base exploded during an outdoor concert, resulting in more than two dozen deaths. After the incident, the artist insisted on keeping the damaged sculpture on site, a reminder of the lives lost. In 2000, he installed an identical piece next to it.

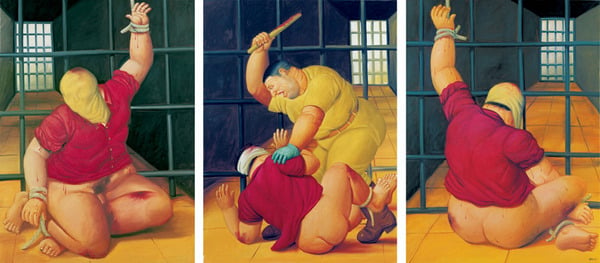

Fernando Botero, Abu Ghraib 43 (2005).

Courtesy Marlborough Gallery.

One of Botero’s most impactful bodies of work came late in his career. In 2005, he debuted a suite of paintings based on photographs of American military members abusing prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Whereas many of the artist’s previous efforts were met with mixed reviews, the Abu Ghraib series arrived to near-universal acclaim, recasting Botero as a deft observer of political violence.

“These paintings do something that the harrowing photographs taken at Abu Ghraib do not,” New York Times critic Roberta Smith wrote at the time. “They restore the prisoners’ dignity and humanity without diminishing their agony or the injustice of their situation.” Smith argued that the paintings “hold art and politics in balance, creating the needed buffer to help us face the unbearable and maintain some hope.”