Archaeology & History

CT Scans Unlock Secrets of Mummified Individuals at Field Museum

The museum is praising the new approach as a more respectful method for engaging with the deceased.

The museum is praising the new approach as a more respectful method for engaging with the deceased.

Verity Babbs

Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History has given researchers the opportunity to learn more about the ancient individuals inside mummies, without needing to disturb their delicate wrapping.

A mobile CT scanner was parked outside the 130-year-old museum for four days this summer and 26 mummified bodies from the Field Museum collection were scanned. Without needing to disrupt the ancient preservation of the bodies, researchers were able to learn about “each deceased person’s individuality and reveal what their community thought important enough to bring with them to their eternal after lives.”

The Field Museum contains artifacts from around the globe, including several mummified bodies of both humans and animals, as part of its 24-million object collection. Perhaps the most famous mummified individual in the museum’s collection is Harwa, who lived as the doorkeeper of a granary in Egypt around 3,000 years ago. Harwa is famed for having been the first mummified person to fly on an airplane in 1939, and the first mummy to get lost in luggage after being flown to San Francisco by mistake in the early 1940s.

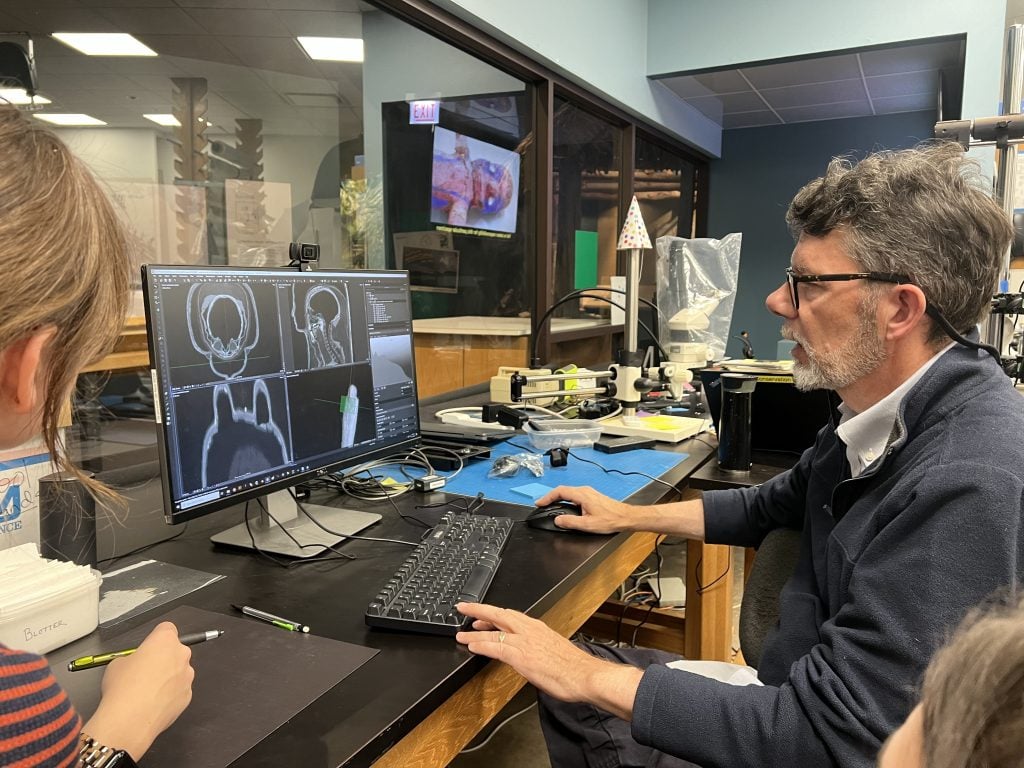

Researchers at the Field Museum scan a mummified individual. © The Field Museum 2024, Photo: Morgan Clark.

CT scanners work by building up a three-dimensional picture made up from thousands of X-ray images captured by the machine, and the technology has already provided researchers with the answer to a mystery about one of the Field Museum’s mummified individuals.

The 3,000 mummified remains of the Lady Chenet-aa, who lived during the Third Immediate Period of Egypt (1070–664 B.C.E.) had archaeologists scratching their heads as there did not appear to be a suitable point of entry for her body inside her funerary box, known as a “cartonnage.” CT scans were able to detect a small seam down the back of the cartonnage, revealing that her body would have been stood upright and the coffin—softened with humidity to become malleable—was slit from head to foot and held open before being lowered down over the body and seamed together.

The analysis also shed new light on Harwa. Scans revealed that he lived to a then-ripe old age of early to mid-40s, with his remains showing no signs that would indicate a life of hard, physical labor. His immaculate teeth, too, further suggested he led a comfortable life marked by his high status and access to quality food.

Researchers at the Field Museum scan a mummified individual. Photo: © The Field Museum 2024, Photo: Morgan Clark.

The museum’s announcement further highlighted the need for a more sensitive and person-centered approach to research on mummified remains.

While “mummies are often thought of as scary or grotesque creatures with glowing eyes and tattered wrappings,” the statement read, “mummified human remains offer us an incredibly personal insight into the lives of individuals who lived more than 3,000 years ago… Today, our standards of care for human remains emphasize them as individual people deserving of dignity and respect.”

Field Museum researchers analyze a composite scan of a mummified individual. © The Field Museum 2024, Photo: Bella Koscal.

Stacy Drake, the human remains collection manager at the museum added that “it is incredible rare that you get to investigate or view history from the perspective of a single individual… this is a really great way for us to look at who these people were—not just the stuff that they made and the stories that we have concocted about them, but the actual individuals that were living at this time.”

The museum plans to continue its CT scan research through 2025.