Russian brothers Mikhail and Ivan Morozov amassed one of the world’s strongest collections of Impressionist and Modern Art. But their world-leading collection was nationalized in 1918 after the Bolshevik revolution, and fell into obscurity for decades.

Now, for its exhibition, “The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art,” on view through February 22, the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris has reunited around 200 artworks from the collection, which is now mostly dispersed between the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, and the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. The works by Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Monet, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Bonnard come from the first two museums, the works by Russian artists from the latter.

“Reuniting all these pieces from major collections was very complicated and an enormous diplomatic undertaking,” Anne Baldassari, the exhibition’s curator, told Artnet News. The diplomatic significance was evident at the opening, which was attended by French President Emmanuel Macron and the Russian culture minister, Olga Lioubimova.

Installation view of “La Collection Morozov. Icônes de l’art moderne,” at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris. ©Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage.

The feat of showing the Morozov collection outside Russia for the first time is a “landmark” event, said LVMH’s president, and art collector Bernard Arnault. It was achieved partly thanks to the Fondation Louis Vuitton helping the Russian museums restore works by some of the artists and being involved in organizing the Morozov exhibition at the Hermitage in 2019.

This is the second exhibition at the Frank Gehry-designed Fondation Louis Vuitton that Baldassari has curated on major Moscow collectors—the first was devoted to Sergei Shchukin in 2016 and 2017. “[Had their collections not been seized during the Bolshevik revolution] Shchukin and Ivan Morozov had the idea of joining their collections to create a big museum, which would have constituted the most extraordinary museum on French art in the world,” Baldassari said.

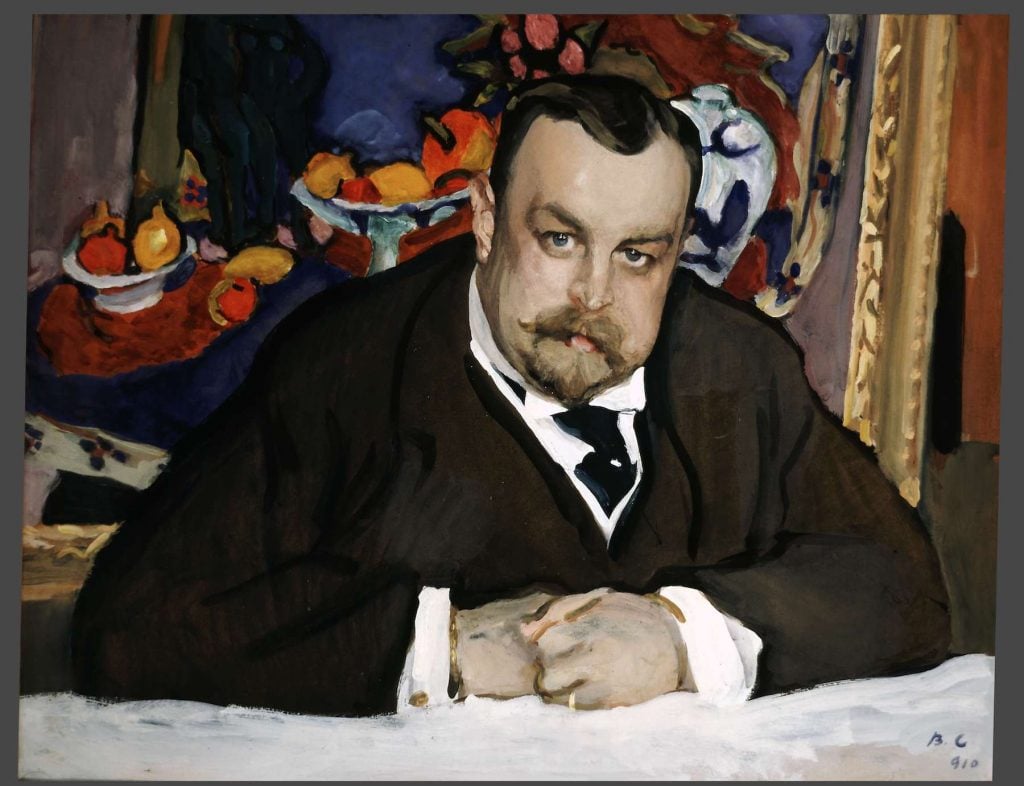

The history of the Morozov collection is a family saga. Mikhail and Ivan Morozov, born in 1870 and 1871 respectively, were the great-grandsons of a serf. With five rubles from his wife’s dowry, their ancestor set up a ribbon workshop, which developed into a factory, and bought his family’s freedom. In a few generations, the family—who were Old Believers (opposed to reforming the Russian Orthodox Church)–became wealthy, philanthropic industrialists. The first room in the exhibition features paintings of their circle by leading Russian artists of that era, such as Mikhail Vrubel and Valentin Serov.

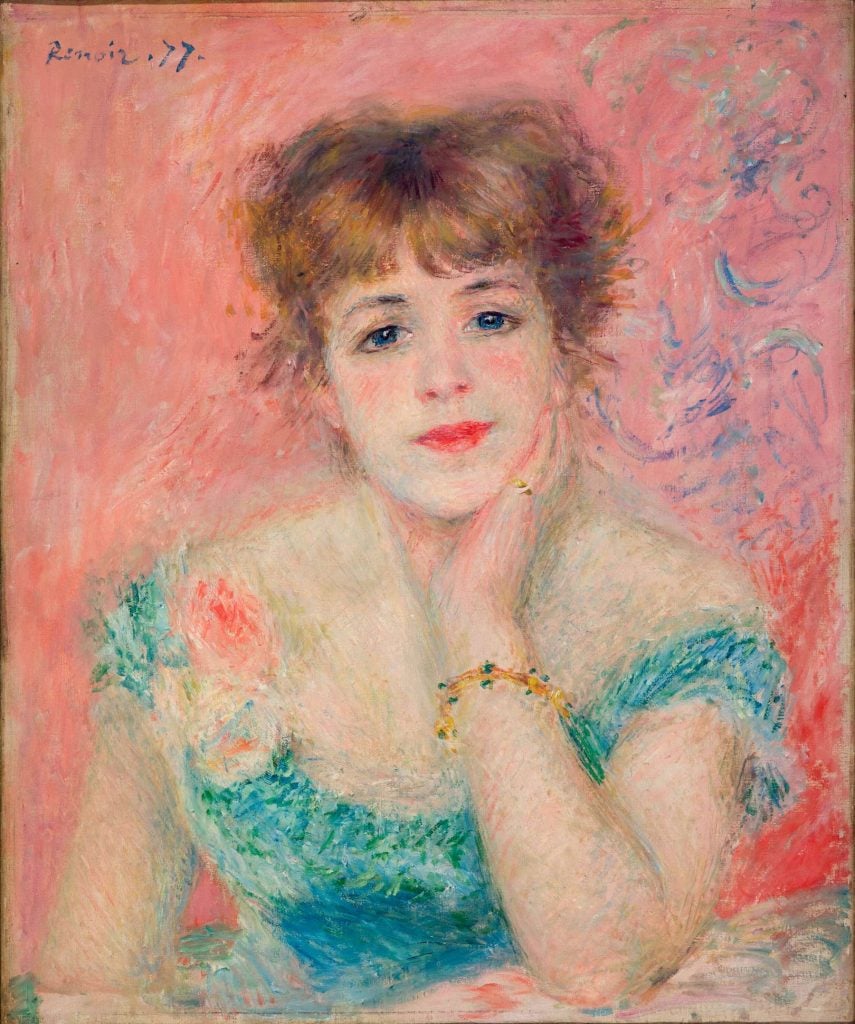

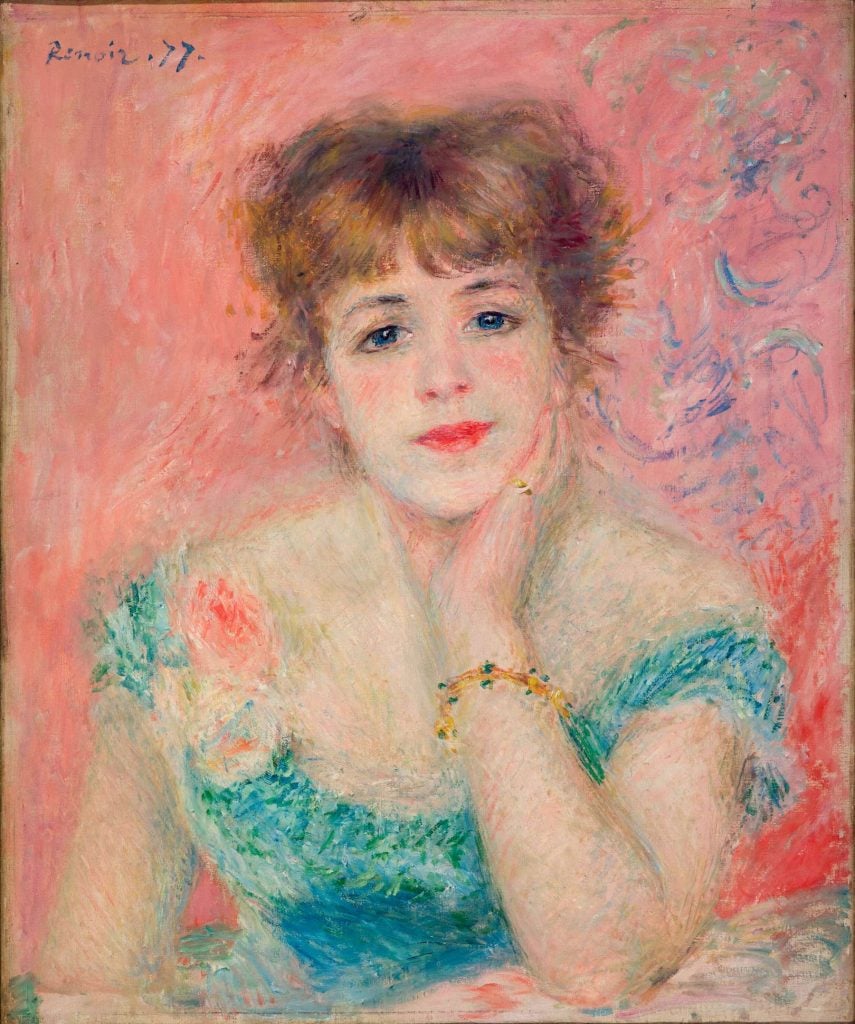

Auguste Renoir, Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary, Paris (1877).Coll. Ivan Morozov, 26 November 1904. Musée d’Etat des beaux-arts Pouchkine, Moscou / Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

At the turn of the last century in Russia, the upper social echelon spoke French and the Morozov brothers formed their stupendous collection on the advice of Parisian dealers such as Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard. Mikhail, who died prematurely at the age of 33, discovered Bonnard’s work in Paris and acquired the first paintings by Gauguin to enter Russia. His brother later commissioned Bonnard to decorate the main staircase of his mansion. Ivan Morozov adored the work of Cézanne—indeed, having tried their hand at landscape painting in their youth, the brothers felt affinity for the landscape genre—and acquired 18 works by him.

Black-and-white photographs displayed at Fondation Louis Vuitton give a sense of the splendor of Ivan Morozov’s mansion and its painting galleries. Some were taken by Maurice Denis, who was commissioned by Ivan Morozov to paint large panels on the story of Psyche for his music room, which has been restaged in the exhibition.

After the Morozov collection was nationalized in 1918, Ivan Morozov fled to Finland and died in Karlsbad, Germany, at the age of 49. The collection would form part of the Museum on Modern Western Art, which Stalin ordered to be closed in 1948, dispersing its contents between the Pushkin and the Hermitage. The Soviet state sold several works for economic reasons, including Van Gogh’s Café de Nuit (now in the Yale University collection) and Cézanne’s portrait of Madame Cézanne (now in New York’s Metropolitan Museum). But things could have been worse. “Stalin hated [Western] art and could have asked for its destruction,” Baldassari said of the danger posed to the collection.

The curator began researching the Morozovs by traveling to Russia and studying the archives in 2014. Several works, including a painting by Gauguin, that had “suffered in storage” were restored with support of French expertise and high-tech equipment. Others will require more elaborate restoration techniques in order not to risk damaging them. “Some of Van Gogh’s marvelous works couldn’t come—such as the only painting that Van Gogh sold in his life-time, Red vineyard in Arles,” Baldassari said. “Ivan Morozov purchased it from a young Belgian artist who had bought it from Van Gogh.”

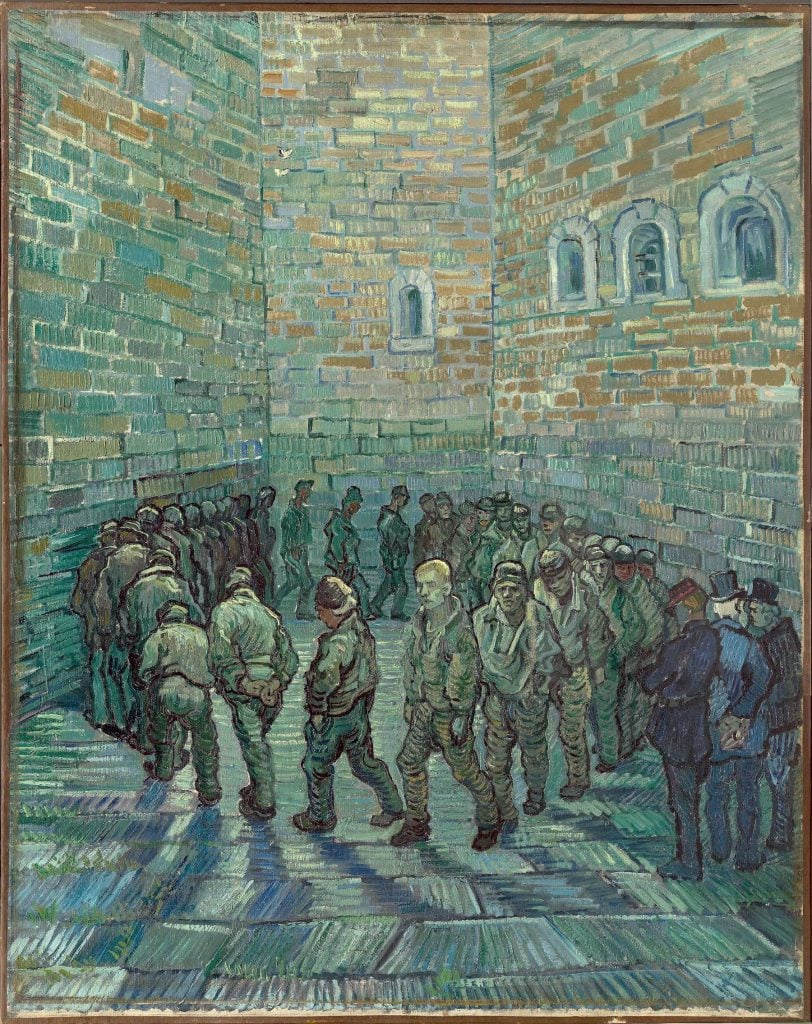

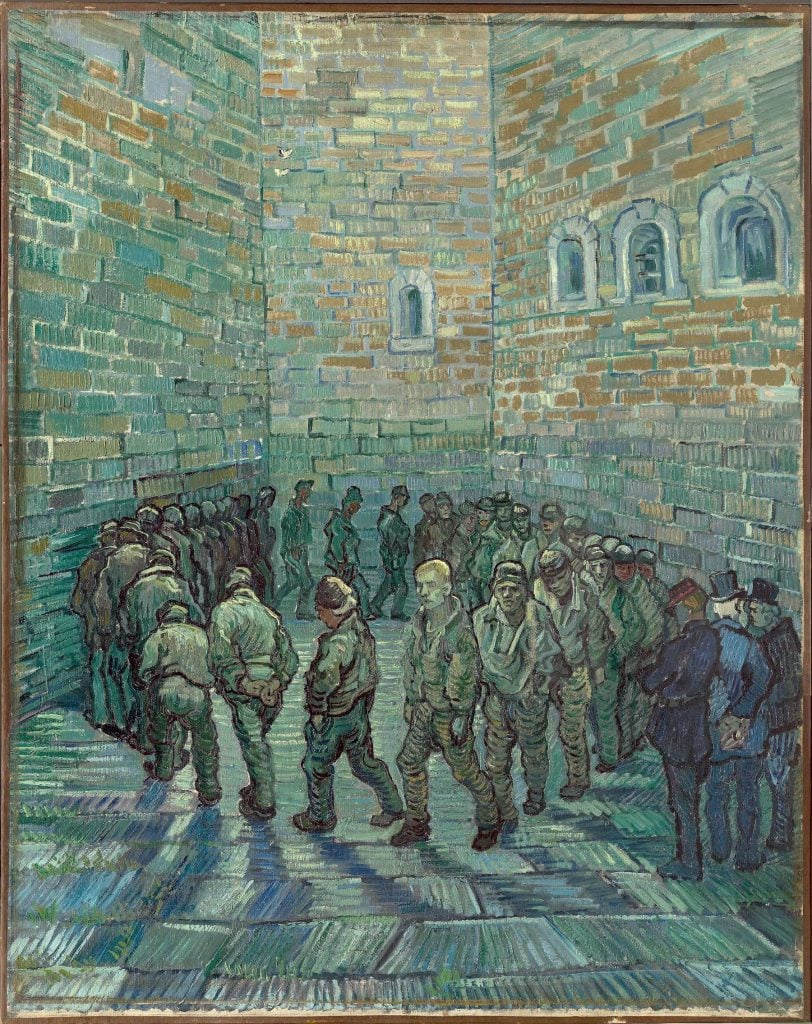

Vincent Van Gogh, The Prison Courtyard, Saint-Rémy (1890). Coll. Ivan Morozov, 23 October 1909. Musée d’Etat des beaux-arts Pouchkine, Moscou / Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

However, Van Gogh’s The Prison Courtyard (1890), which he made while in the Saint-Rémy-de-Provence psychiatric hospital, has made it to Paris. The artist’s brother Theo had sent him a photograph of Gustave Doré’s drawing of a London prison’s courtyard which Van Gogh reinterpreted into a primarily greenish blue-hued painting, the conditions of the prisoners echoing his own confinement.

Further highlights include Matisse’s Moroccan Triptych (1912-1913) in rich blues, comprising a view from a window, a portrait of a young girl and an entrance to the Kasbah; Gauguin’s lush paintings of Tahiti; Picasso’s Cubist portrait of Vollard, the face dissolving into geometric shapes; Monet’s misty depiction of Waterloo Bridge, and Serov’s striking portraits of the Morozov brothers. What’s also fascinating is how a group of Russian avant-garde artists, the Cézannistes, were ardent followers of Cézanne.

Lifting the veil on this chapter of Russian history “is only at the beginning,” Baldassari says. “Now we need to go back to the [Russian] avant-gardes; there are a lot of points that remain obscure and more research needs to be carried out in Russian museums. What we’ve done on the Shchukin and Morozov collections is like lifting an enormous block; perhaps now more things will be able to come out.”

“The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art” is on view at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, through February 22, 2022.