Art World

For Richard Tuttle, Slow and Steady Wins the Retrospectives (at Tate Modern and Bowdoin)

At age 73, Richard Tuttle is set to have his biggest year yet.

At age 73, Richard Tuttle is set to have his biggest year yet.

Alexandra Peers

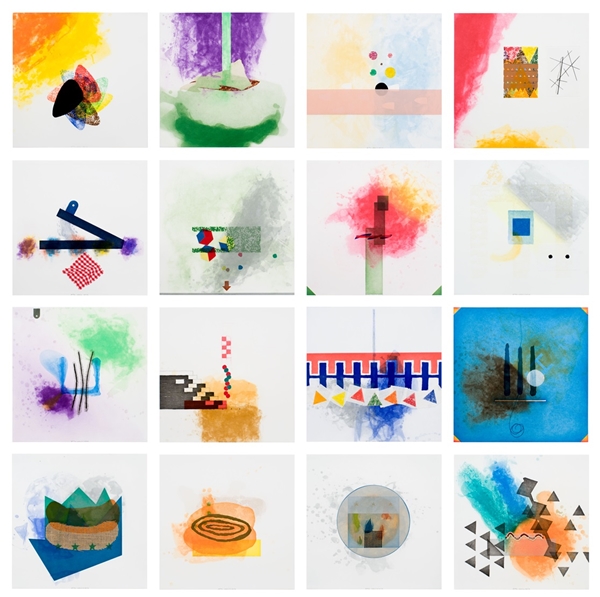

Richard Tuttle, Cloth (2002–2005).

Copyright Richard Tuttle/Brooke Alexander, Inc., New York.

At 73, artist Richard Tuttle is a survivor, but not in the usual sense of simply outlasting your illnesses and enemies. Like a reality show contestant who’s remained on the island by staying under the radar, he’s worked as an artist nonstop for 50 years—and says there has been a strategy to it. “Right from the beginning,” he recalls, in the art world of the mid-1960s, “I saw the overnight careers of artists” and realized “I had to participate in the real world not so much to create a higher profile—I would be a target” but to last as an artist through the stages of life.

He says his first dealer gave him good advice. “Betty Parsons told me: ‘For the real artist, the slowest way is the best way.’”

Perhaps so. In October a monumental installation of Tuttle’s textile work will take over Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. This summer, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, will host a retrospective of his prints, spanning work done over more than 40 years. For the “improvisational objectmaker,” as the New York Times once called him, an artist who uses various media to produce lyrical, elegant work, 2014 will be a good—even overdue—year.

Tuttle talked about prints, the “strenuous” art world, and how radically things have changed in it, as he lounged in front of a gorgeous Albrecht Dürer at the Upper East Side Old Masters gallery C.G. Boerner. (Tuttle is now represented by Pace.) Bespectacled , thin, grizzled, with salt-and-pepper hair and wearing a simple black shirt and beige corduroys, only his shoes give him away as an artist: They’re not only caked with paint but they’re trimmed in a magenta suede.

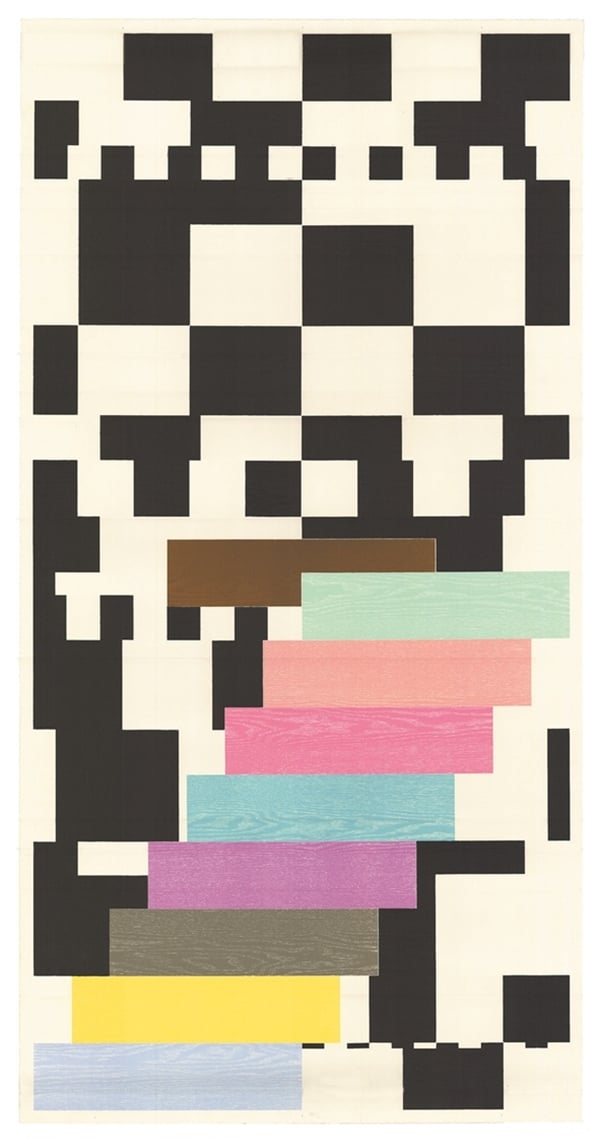

Richard Tuttle, Trans Asian (1993).

Copyright Richard Tuttle/Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

The biggest change in his decades in the art world? Art “is suddenly appearing as a way to escape pain, and it’s a great way.” Says Tuttle: “There’s a lot of pain in contemporary experience,” and people, in order to locate themselves in a confusing visual matrix, are turning to the “historic” comfort of art. As for the business of being an artist, “the art world, with all of its ups and downs, is depressing and strenuous. But you see everything you need to see if you live in the art world long enough, and it helps you.”

The artist was born in Rahway, N.J., and now splits his time among New York, Maine, and New Mexico. Beginning with a job at the Parsons Gallery in 1964, he’s gone on to multiple awards and two dozen museum collections (all the majors). His experience with prints dates back to college, where he did a woodcut for the Trinity College yearbook.

“When I first arrived in the art world, the world of prints was considered the most corrupt,” filled with artists essentially repeating their best-known images for profit, Tuttle says. Now, because it is not distorted by the big money of the contemporary art world, “it is considered the purest.”

Some artists’ best work is their prints, he notes, and praises Edward Hopper’s in particular. “He is really interesting.” In his time, if you “wanted to be an artist, the way to be an artist was the world of illustration, and that led into prints.” For a certain generation of artists, prints were about making the leap from applied arts to fine arts, he explains.

As for him, “artmaking,” says Tuttle, is still “a game of cat and mouse every single day.” Going forward, “I may be making things bigger in size [like his well-known giant Splash tile mural at the Aqua luxury condo complex on Allison Island, Miami], because I think I’m supposed to give the world . . . something.”

Richard Tuttle, Step by Step (2002).

Copyright Richard Tuttle/Universal Limited Art Editions.

The Bowdoin show opens June 28 and runs through October 19. Contributors to the catalogue include Getty Trust president James Cuno.