Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are having a moment in the art world, from museums incorporating these burgeoning technologies into audience engagement strategies, to the plethora of artists using VR and AR to explore the limits of the new medium (to varying degrees of success).

Forensic Architecture (FA) is the latest to dip a toe in, this time exploring virtual reality’s potential as a tool for social justice.

FA was founded in 2010 by architecture professor Eyal Weizman, who recently was in the news for being classified as a security threat by a Homeland Security algorithmic policing program, and as a result denied entry into the US. Coincidentally, he was traveling with his family to give a lecture in California.

Weizman was possibly targeted for undertaking exactly the kinds of projects that his group is best known for: using open-source technology, architectural software, artificial intelligence, and other computer-based operations to investigate human rights violations on behalf of organizations such as Amnesty International and communities affected by political and state violence.

The group does not identify as an art collective, but nevertheless exhibits its work frequently in museums and art institutions around the world. Most recently, the Whitney Biennial presented FA’s Triple-Chaser (2019), a video project that looked into the use of anonymous tear gas canisters on civilians along the US-Mexico and Israeli-Palestine borders, and the weapon’s connection to Warren B. Kanders, a former board member of the Whitney and CEO of Safariland Group—one of the world’s largest manufacturers of such munitions.

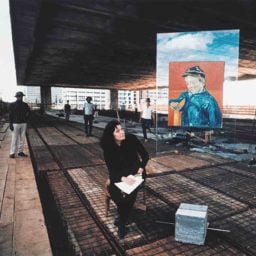

Dean Issacharoff, the soldier accused by Israel of giving false testimony, describes the moment he illegally beat a Palestinian civilian. Courtesy of Forensic Architecture/Breaking the Silence.

Now, Forensic Architecure is putting VR to use on the specific question of witness memory.

Produced with the Museum of Art and Design (MOAD) at Miami Dade College (MDC), FA’s first project utilizing VR technology investigates an incident that occurred in the city of Hebron, Israel. Titled Hebron: Testimonies of Violence (2018–20), the work will be included in the exhibition “Forensic Architecture: True to Scale” curated by Sophie Landres at MOAD, the group’s first major in the US.

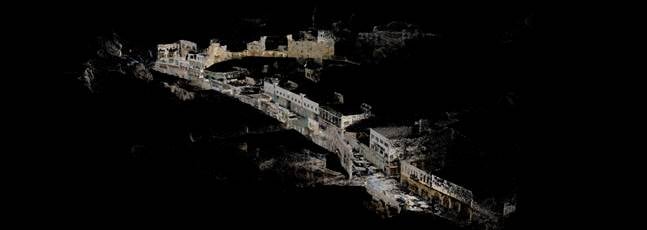

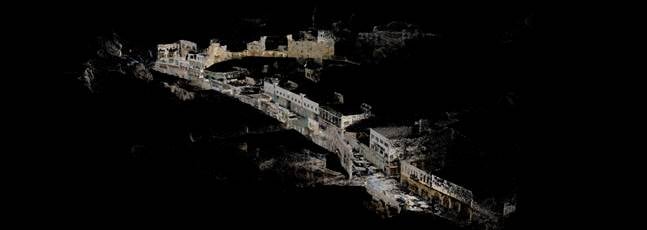

Forensic Architecture used photogrammetry to create a point cloud scan of Shalala Street in Hebron, Israel. Courtesy of Forensic Architecture/Breaking the Silence (2020).

Hebron: Testimonies of Violence came together at the behest of the Israeli activist group Breaking the Silence, an organization of Israeli army veterans that seeks to highlight the situation in occupied territories. In a recent phone interview, Weizman described it as “an Israeli group of whistleblowers—basically soldiers who testify against themselves for human rights violations.”

The main spokesperson for Breaking the Silence, Dean Issacharoff, confessed to brutally and unnecessarily beating a Palestinian civilian during his IDF service in Hebron, in April 2018. An investigation by the Israeli government concluded that the incident never took place and that Issacharoff was lying.

Dean Issacharoff’s point of view in the virtual model as he describes the moment he illegally beat a Palestinian civilian. Courtesy of Forensic Architecture/Breaking the Silence (2020)

To corroborate Issacharoff’s confession, FA decided to meet with two Palestinian witnesses and Issacharoff himself, and use their testimonies to reconstruct the incident in virtual space. Afterwards, FA would determine if their testimonies aligned, and if they were consistent with other video and photographic evidence.

This wasn’t an easy task. Conditions in Hebron, where the historic city center has been under Israeli military control since 1967, have been described as apartheid. The area is plagued by insidious violence. Israelis and Palestinians are rarely in same space.

“We didn’t have access to that place,” Weizman told Artnet News. “I’m Israeli. Part of our team is international and Palestinian. There was simply no place we could meet in Hebron. Or rather, we couldn’t have met at the site where [the incident] happened.”

The photogrammetry scan was used to create a high-resolution 3D model of the alleyway where the controversial beating and arrest took place. Courtesy of Forensic Architecture/Breaking the Silence (2020)

Instead, FA used photogrammetry to create a full-scale 3D map of the area where the alleged beating happened. “We scanned the entire neighborhood in huge detail. We took photographs and turned them into a 3D model. And we allowed the testimonies to actually occur in virtual reality,” explained Weizman. Witnesses, both Palestinian and Israeli, were able to recreate the scene exactly as they had seen it.

The technology allowed the witnesses to locate and move objects and people in space—men, women, soldiers, trucks, guns, etc.—as they recalled the event. FA was then allowed to cross-reference these separate virtual testimonies with real photographs, to see if the testimonies aligned or not.

In this case, FA concluded that they did, verifying Issacharoff’s story.

Superimposition of the models from the three witnesses we interviewed as they describe a convoy of soldiers escorting arrested Palestinian civilians to a militarized checkpoint in Hebron. Courtesy of Forensic Architecture/Breaking the Silence (2020).

The exhibition at MOAD does not present the Hebron: Testimonies of Violence as a VR experience that visitors can use themselves. The group felt that this would have made the project feel like amusement or an attempt to sensationalize trauma and violence. FA instead presents still images and videos of some witness testimonies staged within the virtual space.

Yet the potential use of VR technology as a tool for recalling traumatic memories, is, in some ways, the real core of the work.

Part of the genesis of the Hebron project was looking at the success FA had from building 3D models of bomb sites to help witnesses recall details from traumatic experiences. For example, in Drone in Mir Ali (2018), FA worked with a German woman to recall the details of a drone strike by creating a 3D model of her home where the incident took place. The process triggered memories and details of that in theory would have been lost or never brought to light.

“The problem was, like many other witnesses, they were traumatized and their memory of the incident [was] quite blurry or it [was] distorted or there [were] lacunae in it,” Weizman explained. “And the closer you get to the core of the testimony, to the heart, to the essence, the more the memory becomes difficult.”

Current studies have demonstrated that VR and other immersive virtual technologies may help patients with dementia and Alzheimer’s to recall buried memories. The implication that it may help, in a substantial way, with memories of politically charged events adds another tool to the toolbox of what has been termed FA’s “evidentiary aesthetics.”

“Forensic Architecture: True to Scale” will be on view through September 27, 2020 at the Museum of Art and Design at the Miami Dade College.