Books

Francis Outred on the Explosion of the Contemporary Art Market, and His ‘Judas-Like’ Career Turn From Artist to Auction Exec

Read an excerpt from the book "New Waves: Contemporary Art and the Issues Shaping Its Tomorrow."

Read an excerpt from the book "New Waves: Contemporary Art and the Issues Shaping Its Tomorrow."

Marta Gnyp

This interview has been excerpted from the recent collection New Waves: Contemporary Art and the Issues Shaping Its Tomorrow (September 2021, Skira Publishers), in which art historian Marta Gnyp interviews some of the world’s leading curators, artists, and collectors.

You have been active as an artist and curator; you had a theoretical and art historical background. Was going to an auction house not problematic? A lot of artists, art historians, art critics don’t like auction houses because the valuation there happens through money. There’s been this old conflict between art and money, already Pliny in the 1st century was complaining about degradation of art because of its connection to money. Didn’t you have a problem with exchanging the symbolic value for the financial value?

Obviously that was always an issue; it was even more so in my time; people really didn’t cross that divide at all. For a lot of people, I was like Judas; they felt I’d almost turned my back on the artists. But my position was a relatively creative one because I felt I could make a difference. I never had an issue with the connection between art and money at all. From my perspective, it seemed crazy that great art was being made which was not being appreciated in the artist’s own lifetime and allowing them to continue their careers. I never wanted to go for just a “job” in my life. I looked at it as a kind of mission to try to change the perception of the auction house within various parts of the art world. When I came there, as an artist and curator, I thought that we could show these artworks better than they were being shown at that time. At that point there was absolutely zero interaction between auction houses and artists; I wanted to get the artists who were upset with the auction houses to be more in discussion with them.

Who was the first artist you managed to engage with Sotheby’s?

Damien Hirst in my first evening auction. It was a heart-shaped butterfly painting that Marco Pierre White was selling. Marco and Damien had had a partnership on the Quo Vadis restaurant in London, but they had had a public falling out, and Marco was selling this painting. I didn’t want Damien to feel like he was being ostracized, so I suggested we build enough time to include him in the process. I felt it was an opportunity to get the artist’s viewpoint and input on the presentation of his work which would encourage him to feel involved and therefore supportive of the process. For me, it was a win-win situation and it worked really well. He helped us with the spreads. He gave us different viewpoints and the piece ended up selling to Charles Saatchi. It became one of the big pieces that he promoted as part of his Young British Art group in the second wave.

Then we began to approach more and more artists. If you look at it today, the auction houses approach virtually every single art studio or their gallery to get their consensus on the presentation, because if you get the information wrong, it’s not good for you. That is a part of the legacy I’d like to think I left behind.

Damien Hirst, Love You Always (2014).

[…]

How do you explain that the majority of collectors now are collecting post-war and contemporary art? This wasn’t the case even 30 years ago.

It’s interesting. My father is an antique dealer; he began his own antique enterprise in the 1970s. That was a time when European and English furniture was very popular; the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s were, in a way, the golden period for setting that market. While you can still sell the very special pieces very well, the general market for antique furniture has virtually disappeared. The unsigned works are nowhere and probably worth half or a third of what they were back then. I’ve seen with my own eyes how markets can alter and fluctuate. Part of the reason why contemporary art has become so popular, I would say, is that artworks are relatively portable mirrors to your own life. As people have begun to question the role and meaning of religion in their lives, art provides a different kind of philosophical background. Maybe I’m being too romantic here, but I think art allows the viewer to find other forms of guidance and esprit. Obviously, there are all different kinds of consumers of art in the world, from the investor to the passionate collector, and being one doesn’t necessarily preclude the other. For me, the biggest concern I would have about the future of art is that it continues to remain relevant to us.

Is there anything that could replace art? An object that is at the same time symbolic, visually attractive and historically charged? Hegel argued that religion and philosophy would take over the relevancy from art as the carrier of progress. Do you think that art could still be relevant today?

Yes, I do. I think we’ve seen a golden period of creativity in the last century, specifically in its second half, although the groundwork was laid before. There was an explosion of materials, mediums, concepts, ideas and this sense that anything goes has been a very fertile breeding ground for extraordinary creativity and ideas. Now, the question is, does that explosion just continue ad infinitum, or does it have an end when artworks begin to replicate themselves and no longer have the same power as they used to?

Where do you see the new possibilities then?

I personally look around me today and think about the developments in technology on the West Coast and what the likes of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk and the rest of the tech brains in the Silicon Valleys across the world are doing. I see that as an alternative religion, one that has a different kind of impact on our lives, but certainly brings another kind of philosophy to what we do. You can find a lot of things online which are not necessarily art, but they broaden your horizons, give you meaning in different ways. I think there is competition. That’s why artists have got to be on their toes. I’m getting towards 50, I’ve been in the art world for 30 years; I have a different outlook on the art world to the one I had 30 years ago. I can’t judge when a phenomenon like KAWS comes along. My 13-year-old son happens to love art, so I arranged for his class to go to see Antony Gormley at the Royal Academy on a special tour and then on to see KAWS at Skarstedt. They all wanted to talk about KAWS and not about Gormley. What’s interesting to me is that they have no insight into the market whatsoever. For some reason, KAWS has this incredible ability to speak to a very broad audience and make symbols for a global public. It is a phenomenon which I am still trying to understand.

[…]

In your 10 years at Christie’s you became known as the rainmaker. You have changed a lot in the company and you became the face of Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art. How did you do that? I read about your masterpiece approach, which means that you rather concentrated on the works instead of collectors.

I suppose again, it comes back to my artistic background that my focus lies on the artworks. At Sotheby’s and at Christie’s, the focus was always on client systems, on people rather than artworks, such as the social aspects, the database aspects, and creating this environment where people would bring things to you. It gave you no context for pricing objects, knowing their uniqueness or establishing where they were. When I was at Sotheby’s, I had created an Excel spreadsheet, which was a condensed Francis Bacon catalogue raisonné which didn’t exist at the time. I used that as a basis from which I could understand where all the works were in the world, who owned them, and how we could get to those people, interact with them and create a kind of Francis Bacon world. When I came to Christie’s, thankfully I was given the sort of tools to be able to develop a specific data system. We developed a masterpiece system, which was like a client system but for artworks. We would do mass research projects on each artist and pool all of the available data on each painting from books and online. In my time at Christie’s we built the system and then we created our own version of a catalogue raisonné for 50 artists using all the data resources at our fingertips.

How did you select the 50 biggest artists? How did you gather the information about where the works are?

Obviously, it’s a piecemeal process. At the beginning you do one or two artists, and it’s very much focused on the market, both in the present and where you see it going in the future. This system needs to be ahead of the market and keep you prepared for developments, so that you can respond smartly and efficiently. The 50 artists were built gradually over 10 years pulling information from a whole variety of different places. We built the system from scratch in Europe and it was then adopted by New York and in about five or six years it became a global cross-departmental approach with an expanded group of employees developing it. We used it not just to find objects, but also to help us with pricing so that if something came to us we could very quickly understand what the context of that piece was which helped to inform the valuation.

Except Francis Bacon and Peter Doig, who were the other artists on the list?

I can’t give away all my trade secrets!

How did you price the works?

I remember the first time at Christie’s. I asked the team to do the research beforehand, then we sat down around a table and they pulled out an object. I can’t remember what it was. I asked, “Okay, so what’s the price?” They looked to me, but I wanted to hear what they had to say. An artwork is valued by a compendium of different coordinates. One of the most important is that you have as many eyes and as many different viewpoints as possible, because that gives you the different perceptions of a work of art. I might find the image of that lady really sexy; somebody else might find it offensive. Where do you find the happy medium? It went from that very basic starting point to much more rigorous discussions around values using the information which was coming from the masterpiece system, from Artnet and from different kinds of valuation viewpoints. You’ve got to look at the owner; has the work been in a private collection for 50 years, is it in a special collection? I suppose my interaction with making art also allowed me to understand the material and how it’s made. When you look at a Kiefer painting, for example, there are many different material qualities to it, many of them positive, but some could also be negative. What I tried to convince the team to do was to use Artnet only as a reference point, not as the reference point. There’s a lot of what I would call lazy valuations, where people just sit in front of their screens and look at Artnet. Your time as an expert is better served being out in the field.

The prices have increased a lot during the last 30 years. Have you never had problems in convincing yourself first and then the potential buyers to pay this huge amount of money for an artwork? Can you really be convinced that a work is worth $70 or $90 or $142 million?

There are two conversations here. The first one is what can you dowith that money other than buy a work of art? That’s an age-old discussion and obviously it’s a concern in the world today. Ultimately, it comes down to how much money somebody has and how much they crave an object. When you’re valuing artworks, you’ve got to have the markets in mind. You’ve got to know who is looking and what their taste is. It’s not just because a big collector wants an Andy Warhol painting that you’ll price any Andy Warhol painting at $150 million; you’ve got to know specifically what they’re looking for. We all know the collector is buying Alberto Giacometti right now, but what’s their Holy Grail? It’s these kinds of questions when you get to the upper echelons that you have to know the answer to. Then what you hope for are the surprises on top.

Francis Bacon, Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969).

Was the price of $142 million for the Bacon triptych such a surprise?

It was probably the pinnacle of my career in the auction business on every level. It was the history of the painting itself, how it had been separated, and then how the parts were brought back together again. And then, what we did with it was really an extraordinary experience across the board.

You knew the triptych before it was sold in 2013.

I was very familiar with it as the story fascinated me. Three Studies of Lucian Freud was made in 1969 when it was exhibited at Galleria Galatea in Turin, but remained unsold. Three or four years later, one specific client asked if he could buy one panel. They sold him this one panel, thus splitting the triptych up and the two other panels were sold four or five years later to another person who then sold them to someone in Japan. The first panel had gone to a hotel in Rome where a guest fell so in love with the painting that he bought the hotel to have the painting in it. Then he wanted to try to buy the other two to reunite the triptych. He managed to buy the second one in the early 1980s for a reasonable price, but when the owner of the third one realized that the aim was to reunite the triptych, he went crazy on the price and buyer and seller could not agree. It finally happened in the mid-1990s that he managed to bring the three together. One of the panels was shown on its own in the Tate in ’85 as a single painting and these individual panels had led their own lives for almost 30 years. Then they were eventually brought back together by this mysterious Italian owner. Because the New York team didn’t have the same level of belief in the piece as I did, it was put in at lot 35. Then as all the interest in the work grew it became apparent that we had to have this painting as a motor for the whole auction. We changed the lot number on the day of the sale to lot 8A, eight being an auspicious number in Asia. We wanted it early in the auction to create an atmosphere. We knew about a lot of interest, but on the actual night, the second and the second last bid came from this young guy that we had no idea about. He had seen the special catalogue of the painting which we’d made, fallen in love with it and came to the auction. I saw him put his hand up at $90 million and said to my colleague, “Where did he come from?” He’d been authorized by the bidding team at Christie’s because his family was capable of buying it.

All thanks to the book.

One of my pride and joys. The book that we made was special. He’d seen the book and fallen in love with the painting as a result. He’d been authorized by Christie’s without anybody telling us that he might bid. He’d never been in our field before but has since become quite active. But on that night, he was one of 10 separate bidders. In a way for me it was hard to continue after that sale because it was the perfect auction experience: everything had gone according to plan or better.

You were right about the price.

I knew what the value could be when the private sale happened. I felt it could go to $120 million because it was that special. When I first sat in front of it, it gave me tingles in my spine. It was just such an extraordinary painting and so perfect in every way. It was about the final moment in the relationship between Bacon and Freud. It was the perfect Bacon because of the mixture of technique, experience, and control. It was a painting that had everything. The condition was perfect. Then to see this whole variety of people coming and bidding; it was totally global with European, American, Asian bidders. The ultimate buyer was a recent divorcee who had built a collection with her husband over many years, but never been allowed to buy a Bacon. She took her revenge by paying the most money that anybody had ever paid for a work of art at that point: $142 million. Another chapter in this masterpiece’s great story.

[…]

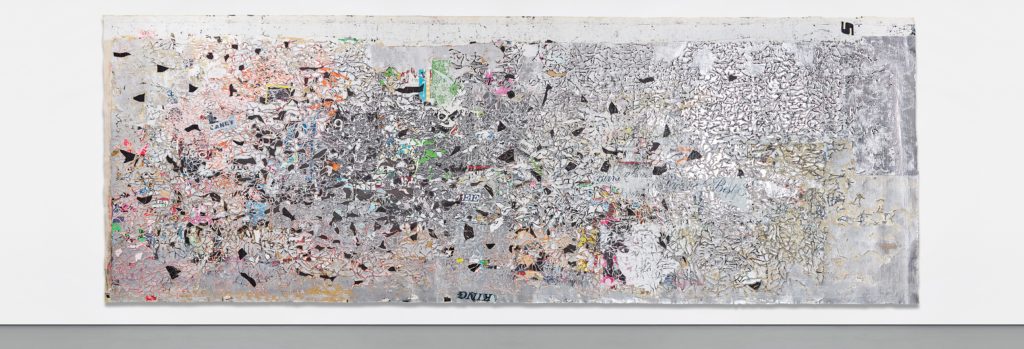

Mark Bradford’s Helter Skelter I (2007) sold for £8.7 million ($12 million). Image courtesy of Phillips/phillips.com.

What have been the biggest transformations of the art system looking from your perspective of the 30 years?

The biggest transformation is that the audience has expanded exponentially. The audience on all levels is probably somewhere between 30 and 100 times what it was. The appetite for the consumption of art in whatever form has transformed. Obviously, the Internet has also helped with that and for me, as somebody doing my own thing, Instagram and Google are very important tools. This transformation of the audience has obviously had a big impact on markets and in turn the market has had a big impact on the industry. As a result, you’ve seen this breakdown of the boundaries between museums, galleries, artists, auction houses and advisors, which I think is very important. All of these different elements are learning from each other now and openly doing so. I think that museums depend more on galleries and auction houses than they have done in the past. Galleries depend on the auction houses’ transparency of price to sell their new works. You can’t set a gallery price for Mark Bradford for $10 million without the precedent having been set at that level in the auction market. Coming back to your original question to me, “How could you as an artist go into an auction house,” I think that if you did it today, it would be much more acceptable. I went to the Christie’s viewing in October in London and saw representatives from the Royal Academy walking around. Museum people are very present at auction house viewings now because they know it’s important for them to understand what’s going on in the marketplace.

Are you involved in the institutional side of the ecosystem?

I’m putting together an exhibition of Francis Bacon with Michael Peppiatt for the Royal Academy which will open in January 2022. It will explore in depth Bacon’s interest in animals and the animalistic in man. I’m also chairing the patrons of the White Chapel and am sitting on the boards of the Contemporary Art Society and The Showroom.

Has the Western art world become really global?

Definitely. If you were to ask me about where the future’s going, I think of course, you’re going to see a lot more from Asia and also Africa becoming more important.

As a center for artists or for collectors?

Both. You’ll see more investment in the art infrastructure and more museums popping up there. I think that it will take time, but the Chinese interests in Africa, obviously on an industrial level, will transfer to a cultural level as well. It’s all interconnected.