Art World

Frank Auerbach: A Dedicated Master

The success of the London School cannot be argued with.

Photo: courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

The success of the London School cannot be argued with.

Amah-Rose Abrams

Frank Auerbach is certainly one of Europe’s—if not the world’s—favorite living painters.

Following the rapturous response to his retrospective “Frank Auerbach,” on view at Tate Britain though March 13, 2016, his work is enjoying a particular resurgence in popularity, offering us the perfect opportunity to revisit his life and art.

A young Frank Auerbach arrived in England in 1939, alone and at the age of eight. His parents had put him on a train to attend school in Kent with the hopes of saving him from the growing power of the Nazi regime. It was at school in England that Auerbach first discovered that he had inherited his mothers’ artistic talent—she had trained as a painter—and developed an interest in acting.

Tragically, Auberbach would never share his creative passion with his parents, as they were were killed in a German concentration camp before they could join their son abroad.

Upon leaving school, Auerbach briefly pursued acting before enrolling at St. Martins School of Art and subsequently The Royal College of Art. It was around this time that Auerbach met contemporaries such as Lucian Freud, Leon Kossoff, and Francis Bacon—who, along with others, were later dubbed “The London School.”

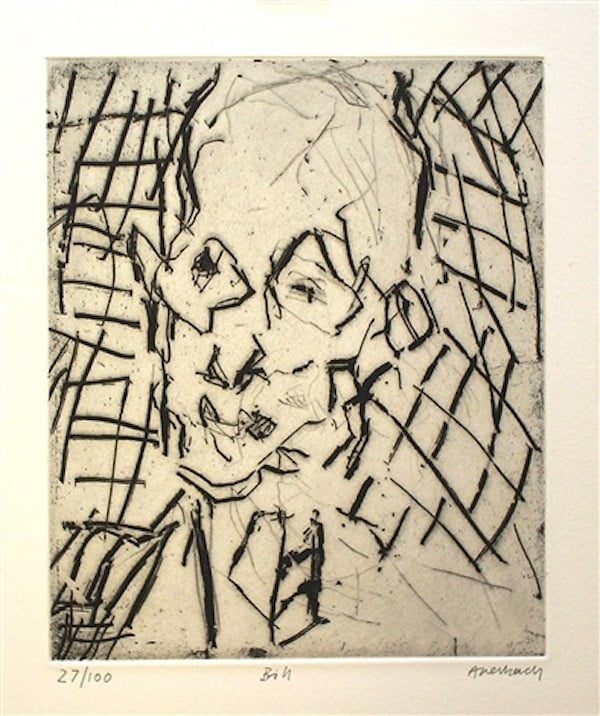

Frank Auerbach, Bill. Courtesy of Nicholas Gallery.

All of Auerbach’s work was profoundly shaped by his relationships. The majority of his paintings are either of Camden, where he has lived and worked for the last fifty years, or Estella Olive West, a fiery actress that Auerbach befriended in his youth, or his wife Julia. Curator Catherine Lampert, who organized the artist’s first major retrospective at the Hayward Gallery in 1978, has also sat for the artist every week since.

Despite the increasingly abstract form of his art, Auerbach’s subjects remain recognizable across bodies of work; their shifting moods palpable through the paint and ink.

Frank Auerbach, Gerda Boehm (Leaning on her Hand), (1980). Courtesy of Water Offerman.

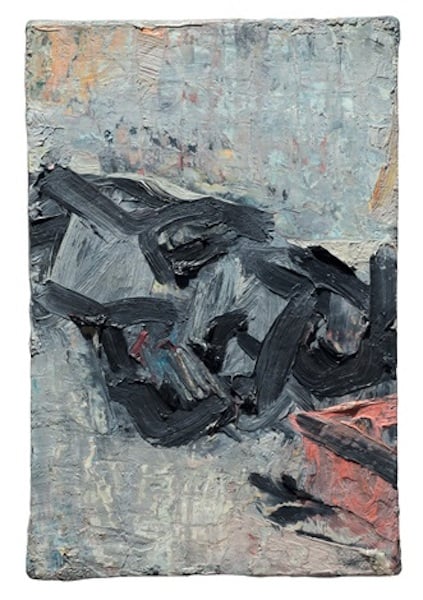

Worked laboriously using layers and layers of paint—seemingly almost built entirely out of paint—elusive subjects disappear and reappear. Auerbach takes a long time to complete a painting, and if it doesn’t look right to him at the end of the day, an entire days’ worth of paint is simply scrapped off and thrown away.

“First that you attempt to do something of a comparable scale and standard, which is impossible; second that you try and do something that has never been done before, that is also impossible,” he was quoted as saying, in the Guardian. “So in the face of this you can either just chuck it in, or you can spend all your energy and time and hopes in trying to cope with it. You will fail. But as Beckett very kindly said for all of us, ‘try again, fail better,’ and painting just took me over. I started off as a superficial person who was attracted to the arts willy-nilly. The more I realized how difficult it was, the more I knew that it was a challenge, that I would feel I had wasted my life if I didn’t try to grapple with it.”

Frank Auerbach, Brigid in Bed, (1974). Courtesy of Ben Brown Fine Arts.

Through this process of drafting and re-drafting, the final layer of paint seems to echo each failed image underneath. As a recent review in The Times mused, “At his best, Auerbach is without doubt our greatest living painter because he captures the soul.”

Following his exhibition at Hayward Gallery, Auerbach was selected to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1986, and was awarded the Golden Lion jointly with Sigmar Polke.

Lucian Freud and Auerbach—who not only shared a profession, but also a childhood in Germany—remained lifelong friends. Sharing a deep trust, Freud would even go so far as to consult Auerbach when hanging an exhibition. Following the death of Freud in 2011, his collection of 45 works by his friend Auerbach—bequeathed to the state in lieu of inheritance tax—was exhibited at the Tate in 2014, setting the scene for the landmark, eponymous retrospective of Auerbach’s work that opened earlier this year.

The strength of that exhibition demonstrates that Auerbach’s dedication to his medium has only deepened with time. Now 84 years old, he still paints 365 days a year, mainly because, he explains, he can’t see a preferable way to spend his time.

Frank Auerbach Reclining Head of Julia (2015). Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

Auerbach comes from a school of painters who starved for their art, gambling on the inevitability of their own success. With nothing to fall back on, he had to rely on his own frugality and consistency, as well as his talent. By remaining in the same area of London, painting friends and family as both they and the city around them changed through the decades, he has created a historical document of the people and places he has loved.

Auerbach’s paintings and drawings are a testament to his dogmatic habits, and his elusive nature only makes him more fascinating to the art-going public who hold him so dear.

You can see “Frank Auerbach” at Marlborough Fine Art through November 21.