Photo: courtesy Vogelsang Gallery

Amah-Rose Abrams

One could never mistake a work by Frank Stella as being by any other artist, despite his enormous influence. A Frank Stella is always unmistakably a Frank Stella.

Upon arriving in New York in the late 1950s after graduating from Princeton University, Stella was uninspired by the painterly style of the Abstract Expressionists. He decided then and there that he would take his work in another direction, more inspired by the flatness of Jasper John’s work.

The retrospective “Frank Stella” is currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which opened on October 30, 2015 and will run through February 7, 2016. This exhibition has not only celebrated the breadth and depth of Stella’s work, but also raised the profile of his work in the marketplace. The museum exhibition is also accompanied by a “One Man Show” at Gary Nader Fine Art, focusing on his sculptural works. Earlier this year, Paul Kasmin Gallery also devoted a solo exhibition to the artist at its 293 10th Avenue location, “Shape as Form,” from September 10 through October 10, 2015.

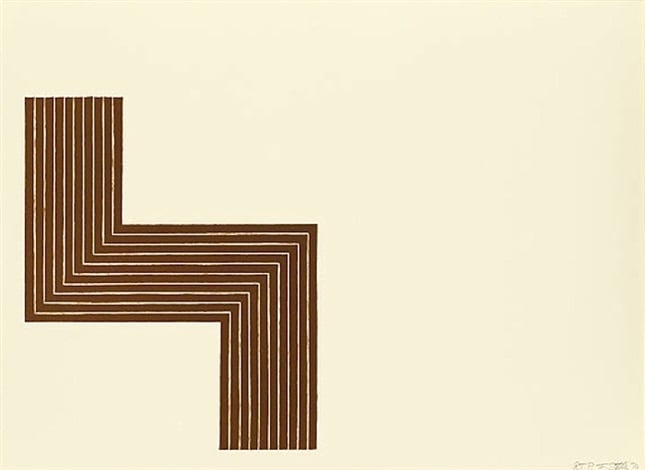

In direct opposition to the free, gestural painting style of his contemporaries, Stella initially turned to stark geometry and straight lines in his infamous Black Paintings. These works gained him the nickname “the father of Minimalism,” and consisted of Stella covering the entire canvas in black paint in varying patterns of straight lines.

His work was especially striking in comparison to painting stars of the era, like Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline.

“It was wildly exciting to be on the scene, which was smaller but way more intense and interesting than today,” Stella told the Telegraph in 2011.

Frank Stella, Copper Series – Ophir (1970). Courtesy of Gregg Shienbaum Fine Art.

A towering figure in American art, Stella’s work has influenced many other artists such as Carl Andre, Sol LeWitt, and Dan Flavin, as well as contemporary artists like Andrew Kuo and Tomas Saraceno.

Stella’s Black Paintings were received by the New York art world with great enthusiasm, and perhaps the sensible thing for Stella to do may have been to produce more of the same—yet Stella continued to push the boundaries of his ideas.

During the 1960s Stella maintained his linear, almost grid-like aesthetic, but gradually he began introducing colors like aluminum or copper. Later in the decade, he began to use a larger palette and strong, curved lines in his work, which, in turn, led to his use of shaped or curved canvases.

Frank Stella, Suchowola III (1973). Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery.

Stella’s paintings now jutted out of the traditional frame of the painting, creating new forms and quite literally pushing the boundaries of contemporary art at the time.

“Rather than having a painting full of gestures, the painting itself became a gesture,” Stella has since explained.

It was in this decade that Stella made the Protractor Series, with multi-colored, looped curves that are perhaps his most recognizable works. The 1960s was also the decade when Stella began to work with printmaking.

By this point in his career, Stella was hugely successful. His inclusion in exhibitions at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, “The Shaped Canvas” in 1964–1965, and “Systemic Painting” in 1966, were landmark events in the history of American art.

In 1970, he was given a retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art in New York which, at age 34, made him the youngest artist ever to have been asked. Perhaps it was this opportunity to look back over his entire oeuvre that persuaded Stella to finally move from the two-dimensional to the three-dimensional. His trademark shapes and lines separated from the wall entirely, and he began to work in sculpture.

“It was what it was: 10 years of work at a level that other artists couldn’t produce,” Stella said of the exhibition in the Telegraph. “I mean, there were other artists who could have produced shows just as good—but none of them would have been young…. I felt I’d gone as far as I could go. The retrospective was the excuse for starting again.”

Frank Stella, The Great Heidelburgh Tun (1988). Courtesy of Christopher-Clark Fine Art.

The explosion of colors, patterns, and textures within his sculpture divided opinions then as they do now. Some critics continue to rail against these works—arguing they appear to exist mid-movement, and are difficult to pinpoint.

Nevertheless, throughout the 70s and 80s Stella’s sculpture continued to evolve, becoming increasingly large, complex, and experimental. The market had also changed, meaning that Stella and his contemporaries were beginning to make more money than they had in the past.

Frank Stella, djaoek (2004). Ccourtesy of Freedman Art

Stella has always been open about how much it costs to produce his works, meaning that despite the hefty price tags his pieces command, he is not a rich man.

“The 70s were a struggle, and then in the 80s, the market changed, and I just went up with everybody else,” he explained in the Telegraph interview. “There was a lot of income, but I went through it in a hurry. Then the dealers became difficult. Nobody wanted to advance me money because I was such a loser. So I was self-supporting from roughly 1990 to 2008.”

Stella’s devotion to continue evolving is what has made him into the great artist he is today—still shocking, still evolving at the age of 79.