The National Assembly of France has unanimously approved a bill to return historic artifacts to Benin and Senegal that were looted during the colonial era. The vote marks the latest chapter—and an extremely significant one—in the country’s ongoing reevaluation of the African art held in its museums. The objects’ return would mark the first official restitutions since France’s president Emmanuel Macron first declared his intention to return looted African objects in 2017.

The bill, which still needs to pass the Senate, also suggests a new development on the horizon in French law, which currently states that national collections are “inalienable and imprescriptible,” effectively prohibiting museums from restituting accessioned objects.

At stake are 26 relics, including statues and a royal throne, looted from the Royal Palaces of Abomey (in what is now Benin) in 1892. They are currently held at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac. (The museum reportedly holds more than 70,000 of the estimated 90,000 objects from sub-Saharan Africa in French national collections.) Should the bill pass its final hurdle, as it is expected to, these objects will be officially returned to the Republic of Benin.

Additionally, a sword and scabbard thought to have once belonged to 19th-century West African political leader El Hadj Omar Tall will be returned to Senegal. Though owned by the French Army Museum in Paris, the object is currently on long-term loan to Senegal for an exhibition at the Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar.

Senegal President Macky Sall (right) receives the sword El Hadj Omar Saidou Tall during a ceremony with French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe at the Palace of the Republic in Dakar, Senegal, in November 2019. Photo: SEYLLOU/AFP via Getty Images.

Former French culture minister Franck Riester, who was called to speak to the Assembly after current minister Roselyne Bachelot put herself into quarantine after coming into contact with someone who tested positive for coronavirus, referred to the proposal as a move toward “strengthened desire for cooperation” between France and the West African countries.

Prior to the vote, Bachelot said the bill was “neither an act of repentance nor reparation, nor a condemnation of France’s cultural model, but the beginning of a new chapter in cultural links between France and Africa.”

Benin President Patrice Talon, meanwhile, called the proposed law a “strict minimum” in terms of what he expects from France’s evolving stance on restitution.

“What we want is a general law that authorizes the executive to negotiate with us a comprehensive restitution on the basis of a precise inventory,” Talon told Jeune Afrique last month.

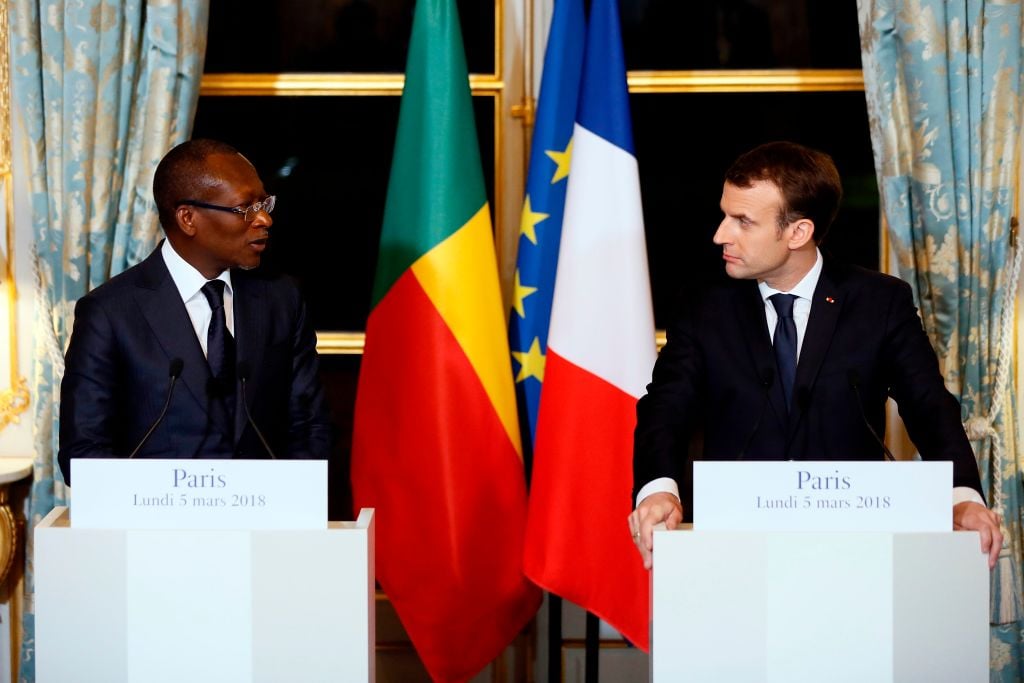

France’s sluggish progress on restitution has drawn criticism around the globe. In 2018, following a landmark speech from President Macron, a historic report commissioned by the government urged France to immediately repatriate all African heritage looted during the colonial era (but offered few practical guidelines for how to go about it). Since then, exactly zero items have been formally restituted.

Macron shone the spotlight on the 26 objects in the Quai Branly, which had long been sought by Benin, back in 2018, when he said they should be returned “without delay.” But the laws in place—which provide French national collections with clear-cut “inalienable and imprescriptable” rights—slowed the momentum. This week’s vote suggests that movement may now be picking back up.