Politics

France Released a Groundbreaking Report on the Restitution of African Art One Year Ago. Has Anything Actually Changed?

The landmark report was about more than just an exchange of objects.

The landmark report was about more than just an exchange of objects.

Naomi Rea

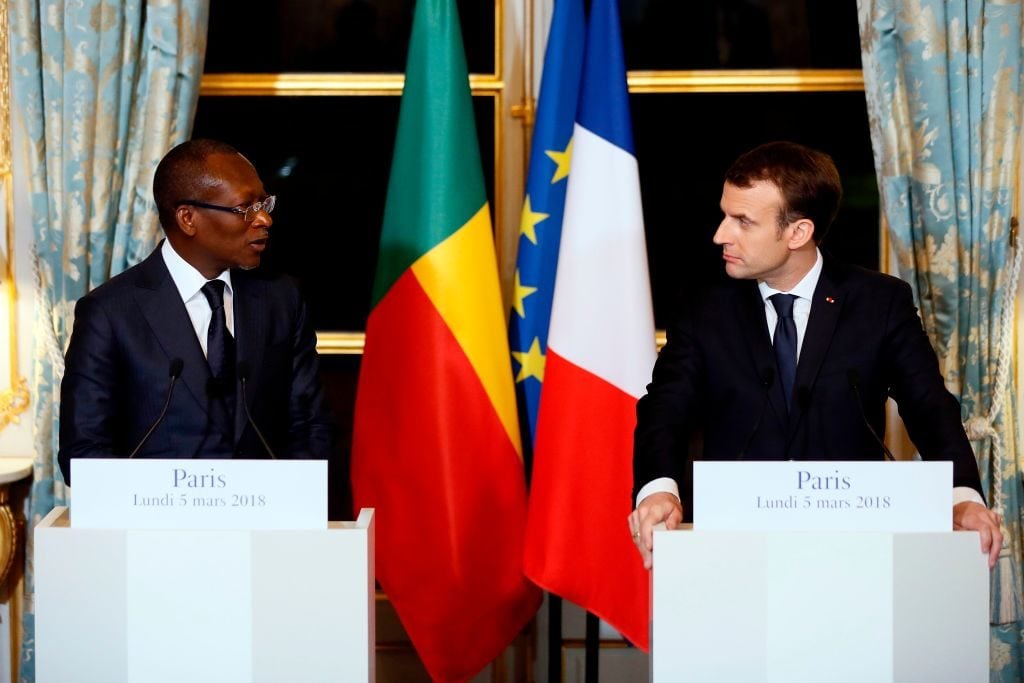

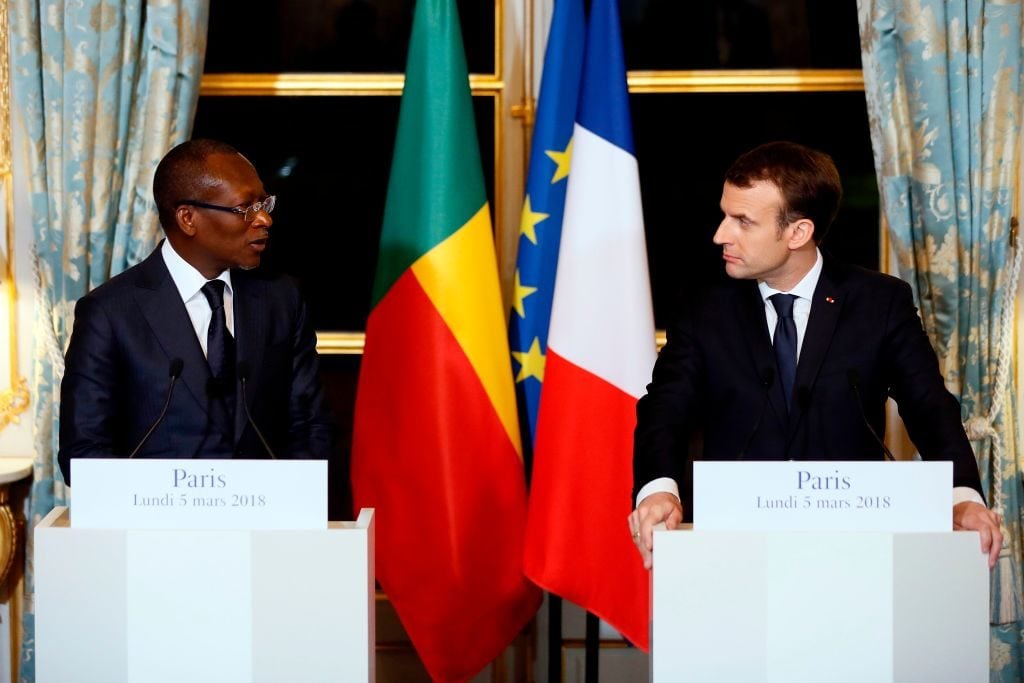

The French president Emmanuel Macron shocked the world two years ago when he made a historic declaration that the former colonial power would strive to return objects looted from Africa to their homelands. In a landmark speech, Macron promised to set the conditions for the restitution of African artifacts held in French national collections within five years.

But two years after that momentous occasion, little concrete action has been taken. “I have the feeling that Macron is not keeping his word,” Patrick Mudekereza, the director of Waza Centre d’art de Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of Congo, tells Artnet News.

At first, it seemed as if things were moving swiftly. On the heels of his dramatic speech, Macron commissioned two academics, the art historian Bénédicte Savoy and the economist Felwine Sarr, to advise him on how to proceed. Eight months later, the pair delivered a report with a shocking verdict (but few practical guidelines): France should permanently and immediately restitute all art taken from Africa “without consent” during the colonial era.

Following publication of the bombshell report, Macron appeared to waste no time in promising to return objects, starting with 26 looted artifacts to Benin. Before long, a fierce debate ignited among French museum professionals who feared this move was a sign that their precious collections would be gutted; around 90,000 objects from sub-Saharan African are held in national collections.

But concerned curators have since piped down: a year after the release of the groundbreaking Savoy-Sarr report, the Benin treasures have still not been sent back. In fact, in the full two years since Macron’s declaration, only one object—a 19th-century saber that returned to Senegal last month—has been restituted from France at all.

Mudekereza says he was initially “very happy” about how far the Savoy-Sarr report went in addressing the issue of looted objects, as well as those taken without sufficient consent or adequate compensation.

“It has opened many possible doors to people who want to work on the topic,” Mudekereza says, praising the academics’ emphasis on the need for a new relational ethics between Western nations and their former colonies. “It’s not just about an exchange of objects, but to understand that it’s mutually beneficial to overcome this burden in history with a new relation that is very fair and transparent.”

Felwine Sarr, at left, with Benedicte Savoy. Photo: Alain Jocard/AFP/Getty Images.

Concrete action, however, has been minimal. A year ago, Macron called for the rapid establishment of an online inventory of French museums’ African collections—but thus far, no such inventory has been made accessible to the public. A promised symposium of museum professionals and politicians, which was slated to occur in the first months of 2019, also did not materialize.

“What we are waiting for now is the moment when the politicians on both sides will open discussions with the professionals, and that is not happening,” Mudekereza says. “And after one year, I think it’s a big problem.”

Inquiries from Artnet News to the French Ministry of Culture, the presidential palace, and the report’s authors Savoy and Sarr went unanswered. But the French minister of culture, Franck Riester, recently implied that the prospect of colonial restitution was proving more complicated than it might have sounded at the outset.

“Let’s not reduce this question to saying, simply, that we will transfer ownership of objects, because it’s much more complex,” he told the New York Times, adding that the French state is looking into the question of restitution as countries make official requests.

Experts cite a variety of challenges that have slowed progress since the report was published. First, there is the pesky issue of French law: Under the current legal system, French national collections are protected with clear-cut “inalienable and imprescriptable” rights, prohibiting museums from permanently handing over accessioned objects. Although the law could be always changed, it remains in place today. (The saber returned to Senegal last month is on permanent loan—currently the only way to restitute an object while getting around the law.)

“The Sarr-Savoy report was inadequate from historical, ethical and practical angles,” says Nicholas Thomas, the director of Britain’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and a professor of art history at Cambridge University. In addition to the legal hurdle, some critics say the report did not address the role that French museums play in conservation—and that African institutions might not have the same resources to preserve these objects. (This particular quibble has been contested by a number of African museum leaders.) Skeptics also note that it is not always clear who is the rightful owner of an object if its original source is a tribe that has since died out.

Cast brass plaques from Benin City at British Museum. Photo: Andreas Praefcke [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons.

Another factor slowing progress, according to Mudekereza, is indecisiveness on the African side. “It’s a problem when African leaders themselves don’t have a kind of clear opinion of what they want,” Mudekereza says. “The discussion among African professionals is not really going at the same level as the discussion between Western museums.” He notes, for example, that although the most immediate concern for the Congo is the return of human remains held in Belgian museums, the Congolese president Felix Tshisekedi has yet to petition the Belgian government for restitution.

France is not the only country that is hoarding valuable treasures plundered from African nations in its collections, although it has done more than any other to at least officially acknowledge the issue. Objects are also scattered in museums throughout Europe as well as some in the US—and France’s declaration has put pressure on them to wrestle with their own responsibilities on the matter.

In the UK, the British Museum alone holds around 73,000 objects from sub-Saharan Africa, including around 400 objects looted from Benin. Like in France, the objects are protected by law from being deaccessioned from the museum’s collection, and the institution seems unlikely to push against that rule.

“We believe the strength of the collection is its breadth and depth which allows millions of visitors an understanding of the cultures of the world and how they interconnect,” a spokeswoman for the museum tells Artnet News.

Over the past year, the museum has continued its efforts to develop and build “equitable long-term partnerships with museums and colleagues across Africa,” the spokeswoman says. Currently, it is focused on the loan of a group of objects to a new culture and heritage centre being developed in Lagos, the JK Randle Centre, which is slated to open in 2020. The objects will initially be loaned for three years with the possibility of extension.

British Museum director Hartwig Fischer with the governor of Edo State Godwin Obaseki, curator Nana Oforiatta Ayim, and the Lagos State tourism commissioner Steve Ayorinde presenting new museum projects in Benin City, Accra, and Lagos. Photo by Naomi Rea.

The museum is also collaborating with the Benin Dialogue Group—a collective of museums from Europe, partners from Nigeria, and representatives of the royal court of Benin—to negotiate long-term loans to the forthcoming Royal Museum, expected to open in Benin in 2023.

In November, the British Museum also organized a three-day workshop in Accra, Ghana, for UK and African museum and heritage professionals, artists, and academics, on the theme of “Building Museum Futures.”

Meanwhile, over in Germany, the country’s federal government has agreed on a set of guidelines to repatriate objects removed from former colonies in “legally or morally unjustifiable” ways, and has set aside €1.9 million ($2.1 million) for provenance research. It has restituted human remains to Namibia as well as a number of other artifacts including a stone cross and a whip.

Exhibition view of “Looted Art? The Benin Bronzes” at MKG in Hamburg. Photo by Michaela Hille

Across the Atlantic, in the US, efforts to fund restitution have been ramping up as well. A grant-making organization founded by the billionaire George Soros recently announced a $15 million, four-year initiative to support the restitution of looted African cultural heritage. The money, overseen by Soros’s Open Society Foundation, will go to African lawyers, archivists, and museum directors working towards restitution as well as NGOs that raise awareness of the topic.

Across the globe, academics and museum professionals are now engaging in these conversations more explicitly and forcefully than ever. Zoë Strother, a professor of African art at Columbia University in New York, organized a major conference on the subject of restitution with the university’s Institute of African Studies in October. But, Strother notes, considering the US has its own laws and precedents, “it remains to be seen how much traction the debate provoked by the Macron Report will have in the American context.”

And in the wake of the slow response to the Savoy-Sarr report, the most concrete actions surrounding restitution may take place outside of official government channels. “The new frontier lies in finding some means for institutions to address ethically claims across international boundaries without necessarily involving nation states,” Strother says, “which do not always have a good record of respecting the perspectives of indigenous peoples.”

Whether museums and experts can translate discussion into action, however, is a question that has yet to be answered.