Archaeology & History

French Love Letters, Sealed for 265 Years, Are Opened—and Read—for the First Time

The letters were written to French soldiers during the height of the Seven Years' War, but never delivered.

The letters were written to French soldiers during the height of the Seven Years' War, but never delivered.

Min Chen

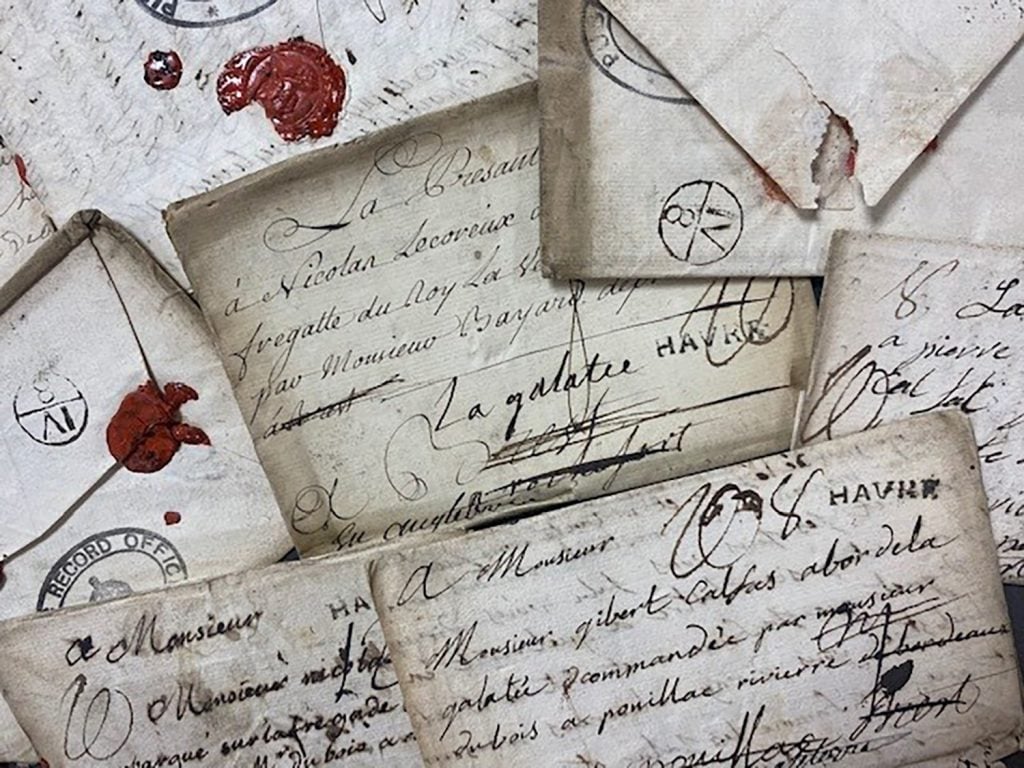

For centuries, a box of letters sat unopened in the National Archives in the U.K., until one curious historian recently unsealed and read them for the first time. What he found was a panoply of human emotion—love, affection, anger, uncertainty, jealousy—intimately recorded at the height of the Seven Years’ War (1756–63).

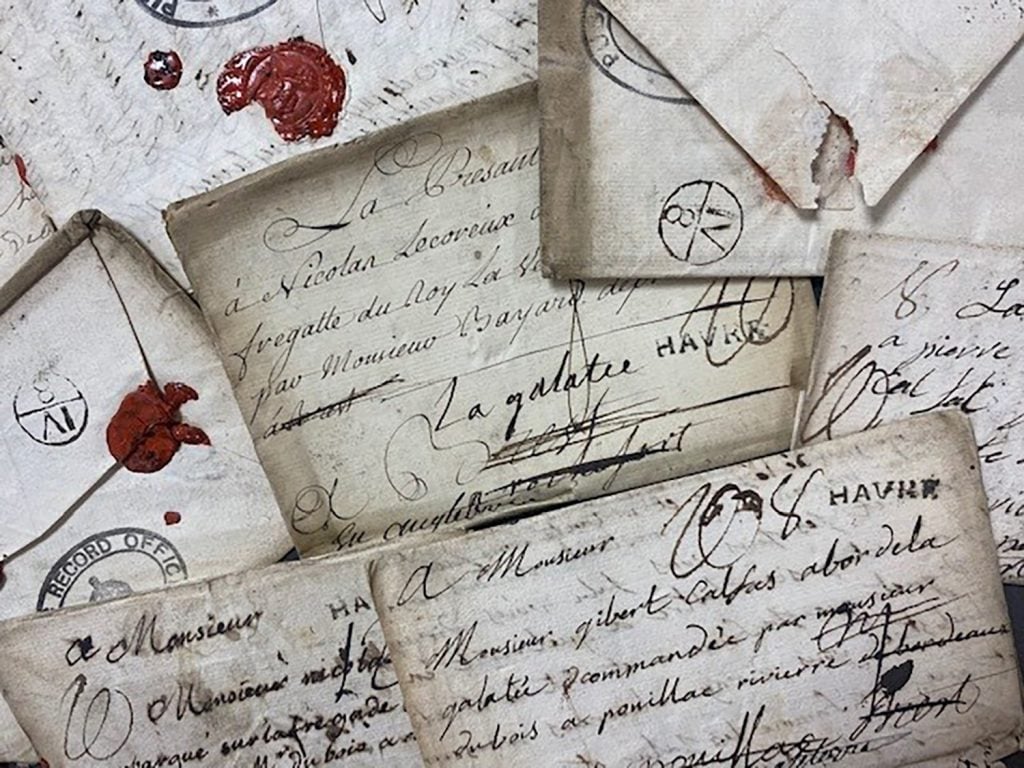

Professor Renaud Morieux from Cambridge University had ordered the box of correspondence from the archives “out of curiosity” while conducting research for his book on the Anglo-French war. In it, he found upwards of 100 letters, bound in three bundles with ribbon, almost all of them still sealed in envelopes with red wax stamps. He would become the first person, he said in a statement, “to read these very personal messages since they were written” 265 years ago.

The bundles of letters Renaud Morieux discovered in the National Archives. Courtesy of The National Archives.

The correspondence dates between 1757 and 1758, during a period when the French and English were deep in a major conflict over territory in North America. The letters were by French writers—wives, fiancés, parents, siblings—and were sent to sailors serving aboard the Galatée military ship, which was headed from Bordeaux, France to Quebec, Canada.

But the transport vessel carrying these letters never reached the Galatée, which was captured by the British Royal Navy, its 181-man crew taken as prisoners of war. The French postal administration then forwarded the mail bag to the Admiralty in London, expecting the agency to deliver the letters to the prisoners. It never did.

Years later, the letters were transferred to the National Archives, where they remained forgotten, until Morieux’s arrival.

“It’s agonizing how close they got,” Morieux said of the Admiralty’s failure to deliver the mail. He added that officials seemed to have opened and read a couple of letters, only to relegate them to storage after discovering they merely contained “family stuff.”

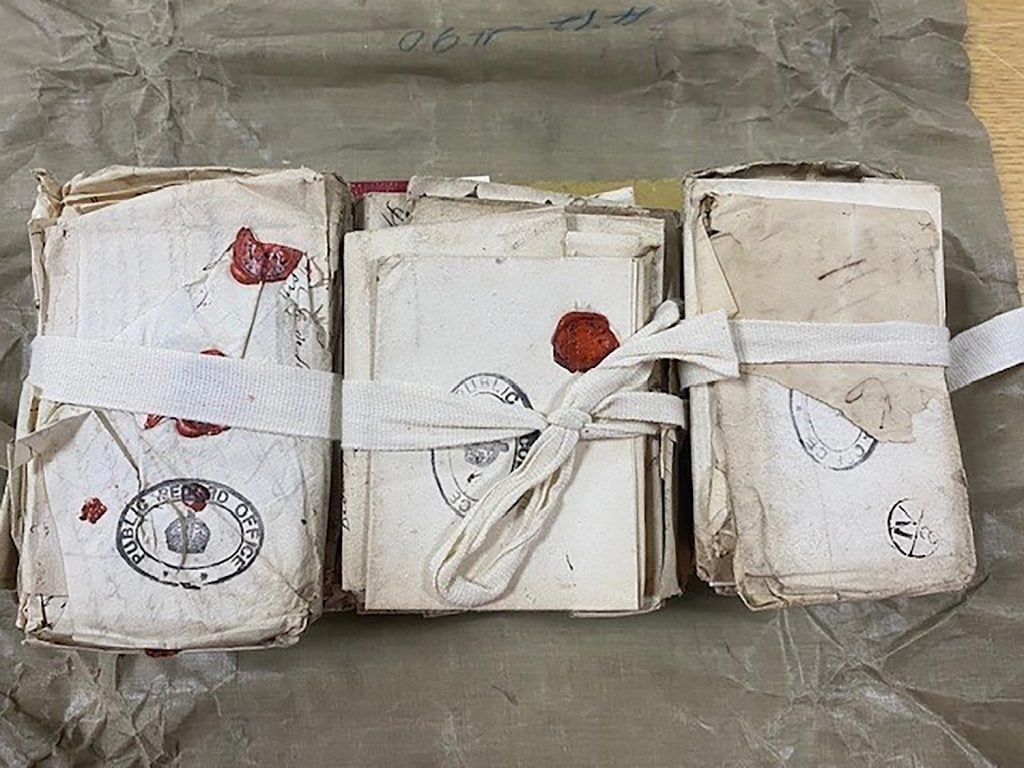

A March 3, 1757 letter from Marguerite Lemoyne to her son Nicolas. Courtesy of The National Archives.

That stuff, however, has offered Morieux rich insight into the lives, loves, and literacy of 18th-century French folk. He spent five months identifying every sailor on board the Galatée and interpreting the letters, finding that 59 percent of them were written by women—to men who would never read them.

“I could spend the night writing to you,” wrote Marie Dubosc to her husband. “I am your forever faithful wife. Good night, my dear friend. It is midnight. I think it is time for me to rest.” (Marie died the following year, before her husband was released; he remarried in 1761.)

In a letter to her fiancé Nicolas Quesnel, a woman named Marianne commended him for writing to his mother after a long silence: “the black cloud has gone, a letter that your mother has received from you, lightens the atmosphere.”

Another woman, Anne Le Cerf, wrote passionately to her husband, Jean Topsent. “I cannot wait to possess you,” she said, before signing off with her pet name, “your obedient wife, Nanette.”

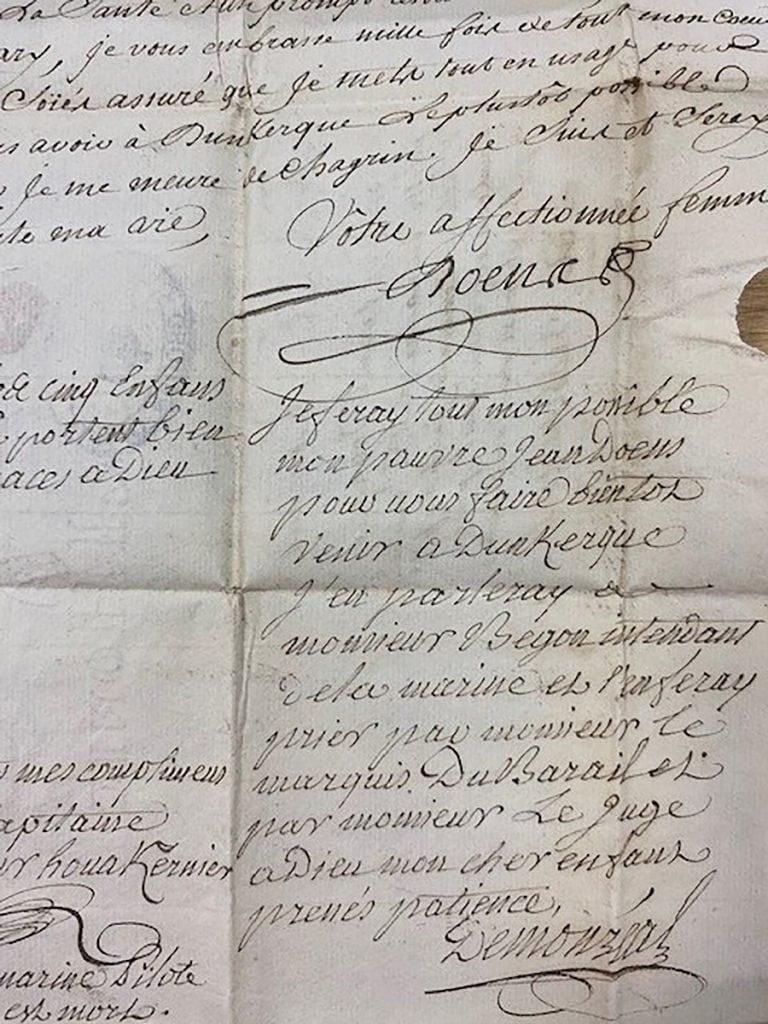

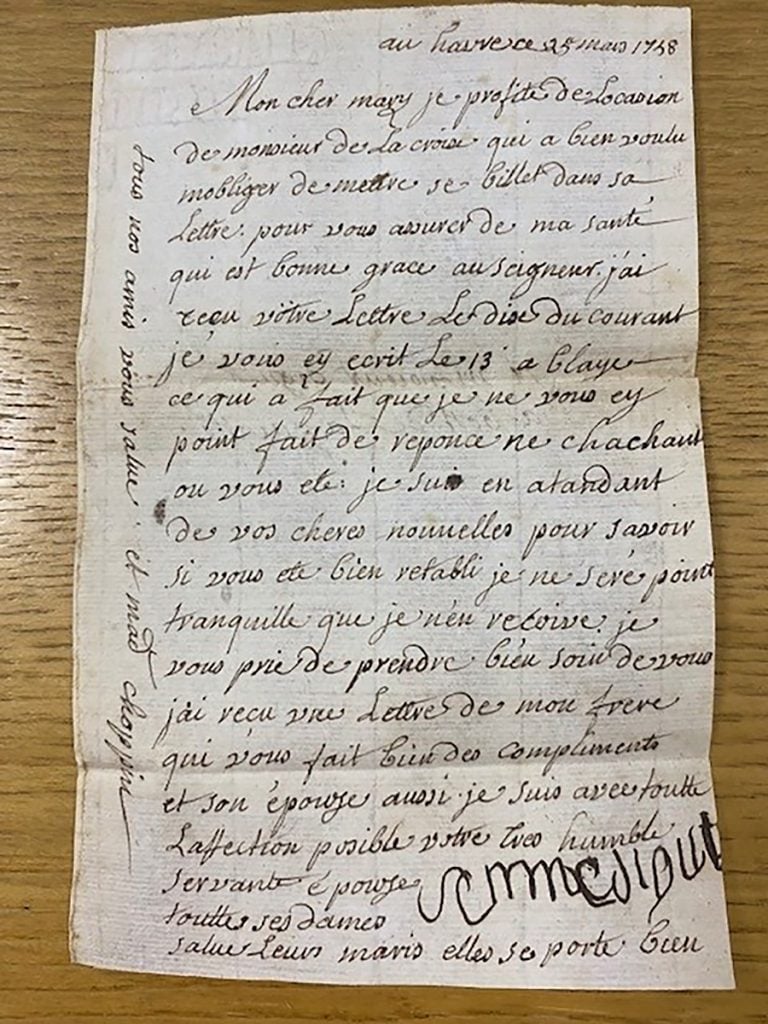

A March 25, 1758 letter from Anne Diguet to her husband, Nicolas. Courtesy of The National Archives.

Most of the letters contained poor spelling and punctuation, some filled to the margins to better maximize the use of expensive paper. According to Morieux, they reflected the lack of literacy among the lower social classes—not that it stopped any of them from staying in touch with their loved ones.

“Most of the people sending these letters were telling a scribe what they wanted to say, and relied on others to read their letters aloud. Staying in touch was a community effort,” he said. “You can take part in a writing culture without knowing how to write nor read.”

Morieux’s research has been published in a study in the French journal Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, capping what he termed an “emotional” inquiry.

“These letters are about universal human experiences. They’re not unique to France or the 18th century,” he said. “They reveal how we all cope with major life challenges.”

More Trending Stories:

Conservators Find a ‘Monstrous Figure’ Hidden in an 18th-Century Joshua Reynolds Painting

A First-Class Dinner Menu Salvaged From the Titanic Makes Waves at Auction

The Louvre Seeks Donations to Stop an American Museum From Acquiring a French Masterpiece

Meet the Woman Behind ‘Weird Medieval Guys,’ the Internet Hit Mining Odd Art From the Middle Ages

A Golden Rothko Shines at Christie’s as Passion for Abstract Expressionism Endures

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

Mega Collector Joseph Lau Shoots Down Rumors That His Wife Lost Him Billions in Bad Investments