Art World

In a New Show, Frida Kahlo’s Art Reflects Her Personal Battles

Some artworks have not been seen for more than two decades.

Some artworks have not been seen for more than two decades.

Devorah Lauter

Frida Kahlo liked to tell people she was born the same year as the Mexican Revolution, in 1910. But the truth is, she was a few years older, born in the Mexico City borough of Coyoacán on July 6, 1907. Her often-repeated tall tale reveals much about her politics, which also come through in her now iconic artworks, as well as her habit of self-construction.

Through her artistry, too, Kahlo crafted an image of herself as a woman at once of strength, with her unwavering gaze back at the viewer, as well as a person of unabashed vulnerability, faced with personal strife and years of physical pain related to health issues. As a result, curators at the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) are asking: Do we really know the mythical artist? In the current exhibition titled, “Frida: Beyond the Myth,” the institution has attempted to understand the artist as an individual beyond what she depicted in her art. On view until November 17, the show travels to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) from April 5 to September 28, 2025.

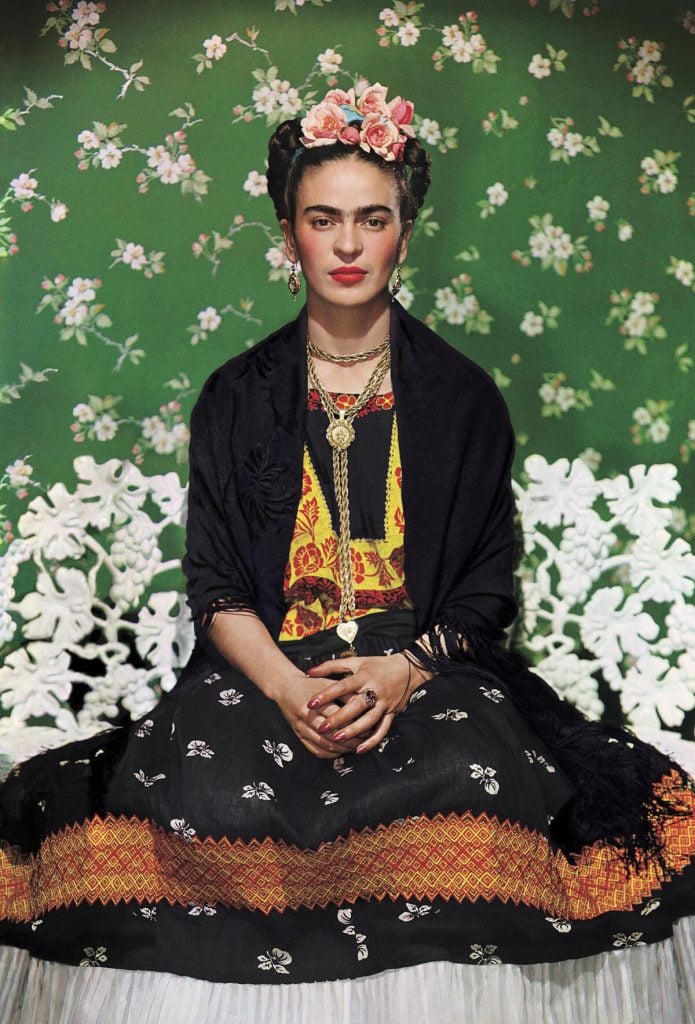

Nickolas Muray, Friday on White Bench, New York (1939), carbon pigment print, private collection. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

“Through this persistent self-fashioning, Kahlo was, in essence, the architect of her own myth—a myth that she was ultimately devoured by,” said Sue Canterbury, the DMA’s Pauline Gill Sullivan Curator of American Art in a statement. “It is only through the eyes of those around her that we are able to get closer to who she really was, seeing her as she was seen and not only as she saw herself.”

The show includes some 30 artworks Kahlo made throughout her life, from 1907 to 1954, as well as about 30 photographs of her, taken by people in her inner circle. The result is a condensed, intimate portrait of the artist’s practice and life.

Frida Kahlo, Diego and Frida 1929-1944, (1944) oil on Masonite with original painted shell frame, private collection, courtesy Galería Arvil, México. © 2024 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

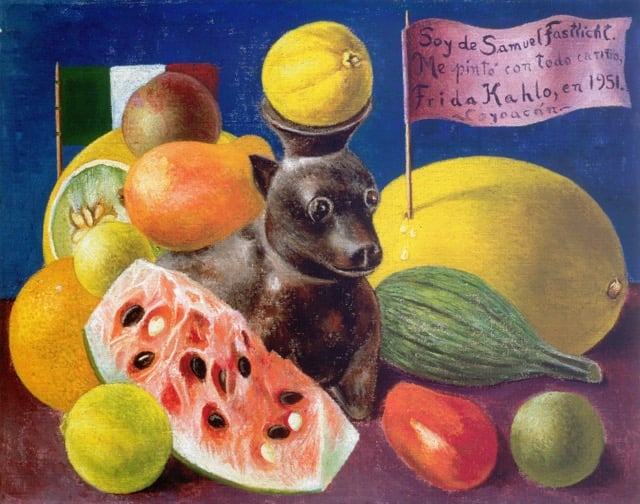

Beginning with photographs by her father, Guillermo Kahlo, showing Kahlo when she was four years old, the exhibit spans her entire life, and pairs works with related images. In one highlight, a 1952 photo shows Kahlo working in bed on her final, completed painting, Naturaleza Viva [Living Nature], which is also hung nearby.

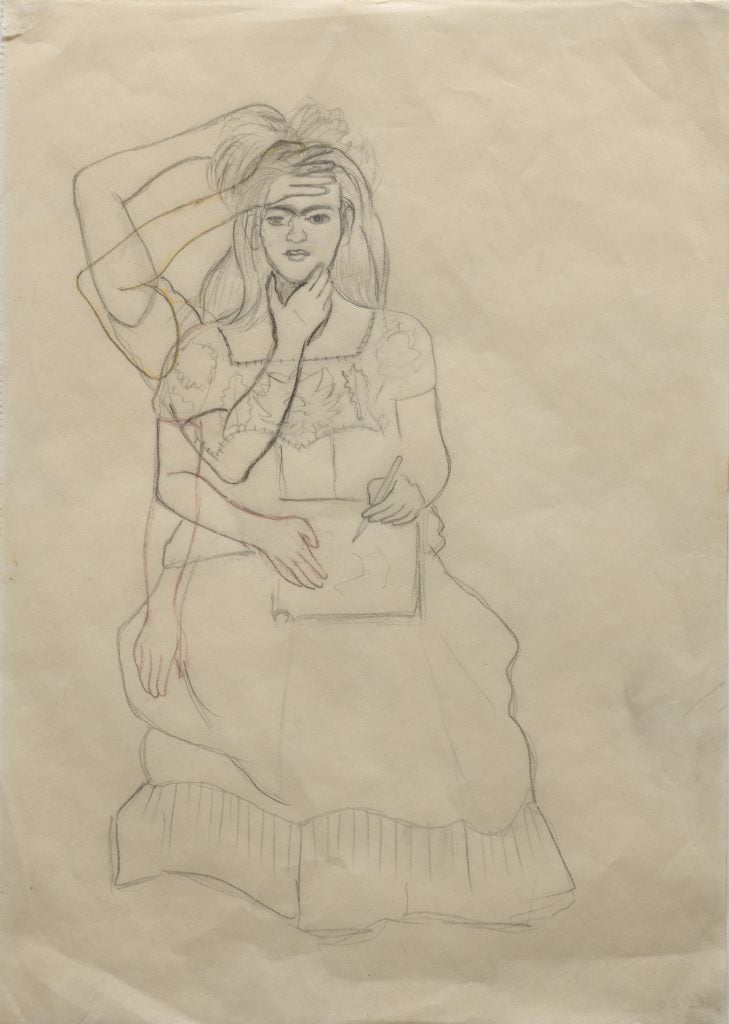

Several of the photographs on view were taken by Kahlo’s husband, muralist Diego Rivera, as well as her part-time lover Nickolas Muray, photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, the Mexican photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo, and art dealer Julien Levy. Interspersed with these, are some Kahlo artworks that have not been seen for over two decades, and rarely leave Mexico, including pastel drawings and sketches.

Frida Kahlo, Sun and Life, (1944) oil on Masonite, private collection, courtesy Galería Arvil, México. © 2024 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A statement about the show argues that even the works the artist created, “which expressed her emotive responses” to significant personal challenges, “hinder our understanding of Kahlo as an individual, as she constructed a persona of opposing characteristics: seductress and victim, strong and vulnerable.” While Kahlo may not have used artwork as a purely autobiographical tool, her paintings remain highly personal forms of expression, leading to the question of what they do tell us, in all their oppositions, about her as an individual artist.

Indeed, Kahlo reveals intimate details from her life in many of her works, which can refer to personal events, including surgeries and subsequent pain she experienced following an accident as a young woman, as well as a complicated marriage.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait Drawing, n.d., pencil on paper, private collection. © 2024 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A masterful, but controversial painting made in 1938 to commemorate the deceased actress Dorothy Hale, is not easily dissociated from the artist’s own inner battles and fraught marriage. Another highlight is the painting, My Dress Hangs There (1933), of Kahlo’s iconic Tehuana dress hanging, as though floating in the center of a tumultuous New York City landscape at the dawn of the Great Depression.

Frida Kahlo, Still Life (I Belong to Samuel Fastlicht), (1951), oil on Masonite, private collection, courtesy of Galería Arvil, México. © 2024 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While her artworks were never meant as autobiographical fact sheets, they instead reveal her voice and view of the world around her through the power of visual language. Combined with the documentary-style photographs in the exhibit, one can learn more about her as a person, though even images can only offer additional interpretations. As for Kahlo’s constructed self, from her paintings, fashion, and fake date of birth, that tendency may tell us more about her than any photograph or accurate timeline of events. Not the other way around.