Art & Exhibitions

How Artists From the Countries Hit Hardest by the Pandemic Vaulted Hurdles to Get to the Venice Biennale

Participants from New Zealand to Kyrgyzstan beat pandemic odds to make it to the event.

Participants from New Zealand to Kyrgyzstan beat pandemic odds to make it to the event.

Rebecca Anne Proctor

Participating in the Venice Biennale has never been an easy feat. To take part in the prestigious event, countries need to secure funding, ship art across the world to Venice, mount an exhibition in a rented structure—most of which are hundreds of years old—and, finally, staff their pavilion for the biennale’s six-month duration.

The usual hurdles were exponentially harder to surmount this year due the dire state of world affairs and the effects of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. For artists and curators from countries that have been hit hardest by Covid-19 or those that have struggled most to foot the bill—presentations require around $100,000 to $300,000, according to several commissioners we spoke to—it’s been a race against both time and resources.

“We are the marginalized of the marginalized—even in the Global South—and we want to change that,” artists Hit Man Gurung and Sheelesha Rajbhandari told Artnet News from Kathmandu, Nepal. The curators of the first ever Nepal Pavilion at the Venice Biennale said it has long been a dream to participate in the celebrated international event, but that financial difficulty and a lack of government support had made it impossible until now.

“The global art scene is always dominated by the powerful countries; the same geopolitics that governs the world governs the art scene,” Gurung said.

Nepal Pavilion curators Hit Man Gurung and Sheelesha Rajbhandari with artist Tsherin Sherpa.

In early January 2021, a group of individuals and private arts organizations decided to change that narrative by making the Nepal pavilion a reality—despite the pandemic, and even though they hadn’t yet secured the funding to do so. “We knew we were going to make it happen and put Nepal on the world stage,” Sangeeta Thapa, one of the commissioners, told Artnet News.

Nepal’s featured artist is Tsherin Sherpa, whose work aims to change what he deems “an international understanding of Nepali art plagued by Western conceptualization of the Himalayan region.” The total cost for the pavilion, including shipping, leasing of the space, travel expenses, and mounting of the artwork will be in excess of $200,000, funding for which was still being raised in the penultimate weeks before the event.

Nepal’s Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation has promised to chip in for shipping costs, but a couple of weeks out from the unveiling, Thapa said the exact contribution had yet to be settled. So far, materializing the pavilion has been helped with support from the Siddhartha Arts Foundation, the Nepal Academy of Fine Arts, Rossi and Rossi gallery—which represents Sherpa—and the Rubin Museum of Art from New York, which has funded 50 percent of costs.

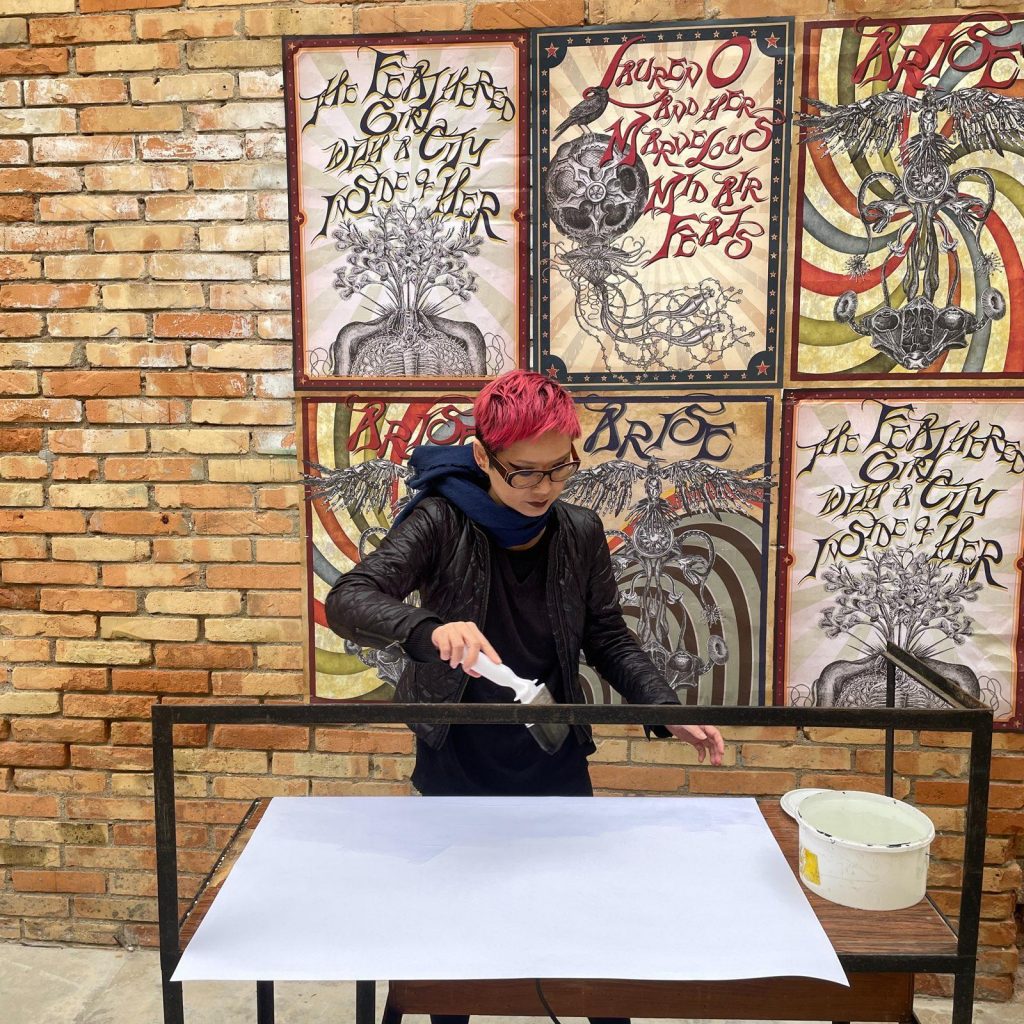

Angela Su: working in progress. Courtesy of the artist.

In Asia, where tough coronavirus restrictions have severely limited travel, effectively imposing geographic isolation on an otherwise well-connected region, artists and curators have had to work extra hard to make it to Venice.

Hong Kong only lifted its flight bans on nine countries and changed the 14-day supervised quarantine period to seven for returning residents a month ahead of the opening. But this hasn’t deterred the team of the Hong Kong Pavilion from coming to Venice.

“There is a full exhibition team in Venice,” a spokesperson from M+, a new museum for visual culture in Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District, which is co-presenting the pavilion with Hong Kong Arts Development Council (HKADC), told Artnet News. The pavilion’s featured artist Angela Su was already on site working with her exhibition team and guest curator Freya Chou. “We are glad that Covid restrictions have not affected the quality or the nature of the work going on show,” the spokesperson said.

While daily life and travel in much of Asia is returning to normal, mainland China continues to roll out lockdowns and adhere to strict border controls. The China Pavilion is a state-run affair organized by the ministry of culture and presented by China Arts and Entertainment Group Ltd. (a state-owned cultural enterprise). The pavilion’s group show will feature the work of four artists—Liu Jiayu, Wang Yuyang, Xu Lei, and the art collective AT art group. But two weeks out from the vernissage of the event Yuyang, who is showing in Venice for the first time, was still unsure of his ability to attend. “I hope my work and myself make it to the opening,” he said.

Some countries, like New Zealand, which had selected its artist—Yuki Kihara, a New Zealander of Japanese and Samoa descent—in 2019, well before country’s severe coronavirus restrictions limited its access to the world, have had to take into consideration the unexpected risk of further restrictions and expensive hotel quarantine when returning home.

“We only confirmed two weeks ago to travel to Venice as a delegation,” Jude Chambers, the pavilion’s project director told Artnet News. “Being able to safely support our delegation to be in Venice was looking near impossible at one point.” While New Zealand has reopened its borders for now, as a contingency, the team is prepared and budgeted to secure rooms in quarantine facilities on their return home in case regulations change quickly.

The financial difficulties caused by the pandemic have also made sourcing funding more difficult than ever, and a few weeks out, the New Zealand cohort was still raising money to cover costs in Venice.

“Fundraising has been the biggest challenge,” Chambers said. “Normally, there are events with the artist and curator to raise funds from potential patrons, but we only managed to offer a limited number due to Covid restrictions. It’s been tough.”

Two Faʻafafine (After Gauguin) (2020). Detail from “Paradise Camp” 2020 series by Yuki Kihara. Image courtesy of the artist and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand.

Other artists have taken the challenge of funding into their own hands. Iranian-born French national Firouz Farmanfarmaian, who is representing Kyrgyzstan for the Central Asian country’s first-ever national pavilion in Venice—the artist shares tribal heritage with the Turanian nomads of Kyrgyz—had to procure his own funding for the presentation.

The total cost needed is more than $200,000, and funds were still being sought when we spoke, through the artist’s We Are the Nomads platform, a production company that produces all his creative endeavors, including exhibitions. While Kyrgyzstan’s ministry of culture signed off on the project, financial resources were diminished by a lawsuit against the government over the health and safety of the Kumtor Gold Mine, one of the largest gold mines in Central Asia, which is responsible for 12.5 percent of the impoverished country’s GDP.

“Our mission is to assist the government to kickstart their cultural tourism industry by assisting them with fundraising from private companies,” Farmanfarmaian told Artnet News. Funding has come from SJ Global Investments, Flora Family Foundation and individual patrons and collections such as Amir FarmanFarmaian, the artist’s and main business partner.

Ayman Baalbaki, who is representing Lebanon during the Venice Biennale, at work on the pavilion. Image courtesy the artist.

Meanwhile for Lebanon, a small Mediterranean country faced with an ongoing economic and political crisis, lack of fuel and electricity and an ever-growing brain drain, not to mention recovering from a devastating explosion to its capital city in August 2020, participating in the Venice Biennale is not high on the list of government priorities. But a group of private donors, artists and a curator, with blessing from the ministry of culture, were determined to gather resources to make it happen.

“This is an entirely private endeavor; the government hasn’t spent a single penny,” Basel Dalloul, one of the main donors, told Artnet News, adding that due to Lebanon’s collapsed banking system, funders had to send money to bank accounts in Paris. “All of us in the private sector have a duty to make sure that Lebanon and its culture stays on the map in spite of all the problems we face,” Dalloul said.

Tanzanian-born London-based writer and curator Shaheen Merali, who is organizing Uganda’s first official pavilion, challenged the idea that for certain countries its more difficult to show in Venice: “It’s a big deal for all nations to present at Venice nowadays—even France or Britain, because our cultures have become recessively more right-wing and funding for anything has become part of the hierarchy of values,” he said.

Merali’s statement echoed others in speaking about their various winding roads to Venice. Despite the unique logistical barriers posed by the pandemic, the biggest problem most have faced has been a perennial difficulty when it comes to staging large-scale art events: securing funding at a time when culture is being deprioritized amid alternative political prerogatives. But as these artists, curators and patrons demonstrate, determination to showcase a nation’s cultural glories, goes a long way.