On View

Gallery Hopping: Mikhael Subotzky Tackles Colonialism and The White Male Psyche at Goodman Gallery

The artist takes on South Africa's colonial past and the student protests of today.

The artist takes on South Africa's colonial past and the student protests of today.

Eileen Kinsella

When protests broke out across South Africa in late 2015 over exorbitant hikes in university fees, artist Mikhael Subotzky says, he was sympathetic to the students’ anger, though not necessarily always in agreement with the ways it was expressed, including acts of vandalism.

“I was really struck by it, but I didn’t want to just go there and photograph the protests,” Subotzky told artnet News during a recent visit to his Johannesburg studio. One focus of the protests at Johannesburg’s University of Witwatersrand, he said, was a building featuring classical architecture, so rich with associations with white, Western culture, which some students had hurled stones at. “It seemed so symbolic that they were attacking this classical architecture,” he said.

In an echo of the destruction and vandalism of artworks during campus protests, Subotzky opted to spraypaint the slogan associated with the protest, “Fees Must Fall,” across his own original photograph of the classical structure.

The work is now on view as part of Subotzky’s fifth solo show at Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg (through April 2). Titled “WYE,” the exhibition features a film installation along with photograph-based works that continue his investigation into South Africa’s tumultuous history.

Mikhael Subotzky, installation view of WYE (2016) at Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery.

The centerpiece of the show is WYE, a three-screen film installation in which individual fictional protagonists travel between England, South Africa, and Australia, regions which form what the artist terms “a temporal triangle where each character is also in a different time period” as a way of exploring colonial mindsets.

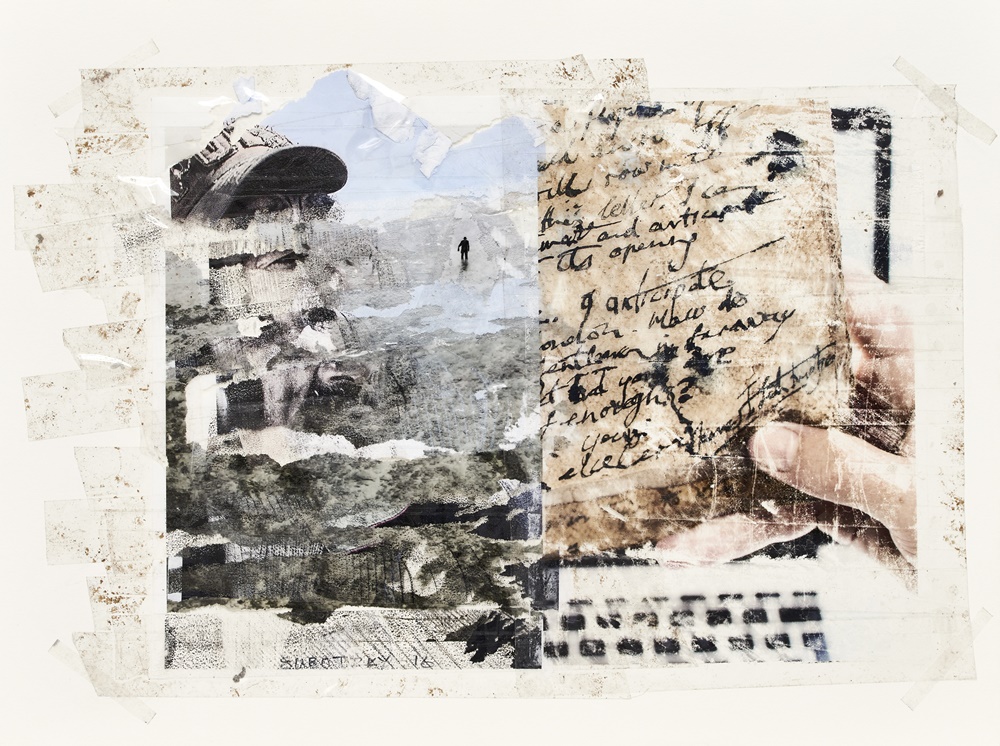

Mikhael Subotzky, WYE Study 21 ( 2016). Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery.

The word wye has multiple meanings, the artist explained: it’s the name of the River Wye, on the banks of which Wordsworth wrote his famous poem about Tintern Abbey at the very time when European industrialists were sweeping into South Africa and Australia. It also refers to the structure of the letter Y, used in engineering and railroad parlance, two of the building blocks of the British colonial project, he notes.

Mikhael Subotzky, Film still from WYE (2016). Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery.

The film follows three characters. The first is an 1820s British settler named Lethbridge who embodies the “intrinsically arrogant mindset” of a 19th-century British settler on his arrival to the Eastern Cape; the second is a 21st-century South African man who walks a Port Elizabeth beach seeking freedom from “politics,” a euphemism for racial problems, says Subotzky, and contemplates fleeing to Australia; the final character is a being with no gender named Fair, who we don’t actually see but who is from the future and has likewise left for Australia.

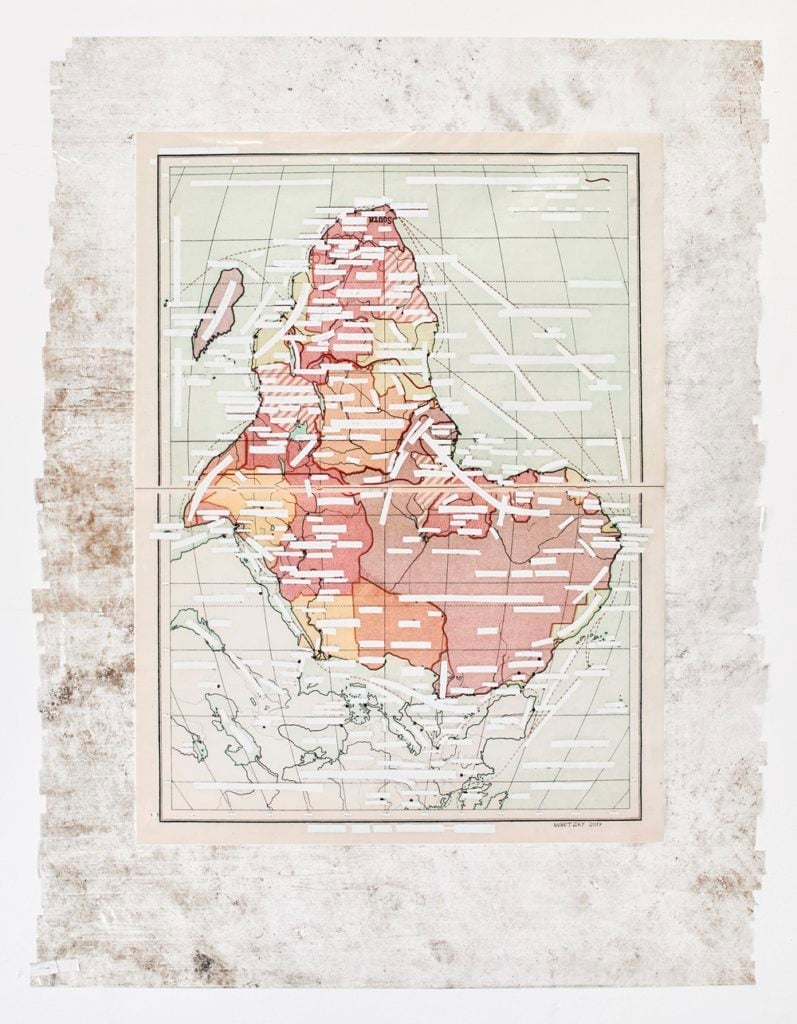

Mikhael Subotzky, Sticky-tape Transfer 22 – South (or Africa-Political and Sea Routes) (2017). Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery.

For Sticky-tape Transfer 22 – South (or Africa-Political and Sea Routes) (2017), says Subotzky, “I instinctively used white tape to cover all the colonial names. For me, it was a way of trying to defamiliarize colonial representation of the landscape. The naming of the landscape is, of course, like cutting it up. It’s very much part of the project of taking control.”

For Subotzky, the work seems to offer a way of symbolically restoring Africa to the Africans, or at least let us look at it with fresh eyes, by turning it upside-down. “What does this land look like when it’s abstracted?”

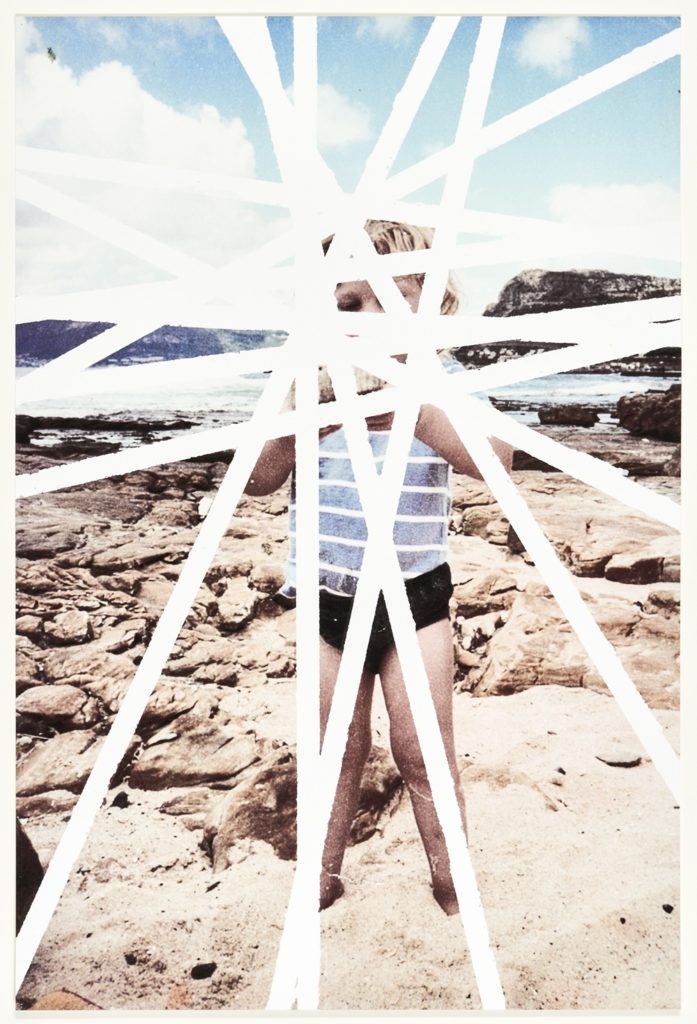

Mikhael Subotzky, Sticky-tape Transfer 27 – Anger (or No Public Thoroughfare after a gas explosion at the Port Elizabeth train station) (2016). Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery.

Mikhael Subotzky, Sticky-tape Transfer 28 – The Diviners (or Pretending My Rock is a Camera So That I Can Be Like Uncle Gid) (2017). Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery.

“Mikhael Subotzky: WYE” runs through April 2 at Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg, South Africa. WYE will be shown at the Maitland Institute, in Cape Town, in September.