Art World

How Gardens Became an Artistic Metaphor for Our Dystopian Times

Precious Okoyomon, Shezad Dawood, and Mat Collishaw are some of the artists exploring cultivated natural environments as part of their practices.

Precious Okoyomon, Shezad Dawood, and Mat Collishaw are some of the artists exploring cultivated natural environments as part of their practices.

Emily Steer

Are gardens the art of the future?

In recent months, several large-scale garden-focused exhibitions have grappled with the relationships between plants and history, technology, the climate crisis, and more. This isn’t to say that flora isn’t a perennial fascination for artists. Many artists have worked with organic materials to comment on environmental collapses as well as the interconnectedness of all life on Earth. Some artists, however, have taken these interests a step further, elevating the idea of gardening to an expansive, awe-inspiring effect. These artists combine ambitious organic or digital plants with music, poetry, and scientific collaboration.

© Shezad Dawood, Night in the Garden of Love (2023) VR environment, produced by UBIK Productions, co-commissioned by WIELS, Brussels, and Aga Khan Museum, Toronto. Courtesy of UBIK Productions

In November of 2023, British artist Shezad Dawood’s exhibition “Night in the Garden of Love” opened at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto (until May 5, 2024). The exhibition responds to the music and drawings of American composer Yusef Lateef while intertwining flora with technology. Alongside textiles, scent, and sound, digital plants grow algorithmically on giant screens and a VR piece leads visitors through a luscious park. “Gardens can suggest our interface with nature, which can be for good or ill,” Dawood explained. “They can create space for community, heterotopia, diversity.”

The context of Dawood’s work is the dire state of the environment. It follows the artist’s long-running “Leviathan” project, which explores the entangled state of mental health, immigration, and environmental collapse in the 21st century. Even still, the work is ultimately optimistic. “In a way, been there done that!” Dawood laughed. “With a lot of the earlier Leviathan films, I was exploring the dystopia to come. Now it’s happened, what’s the point? We need a shift in consciousness. I explore Lateef’s novella Night in the Garden of Love with VR, in which an elderly couple shows you through this dystopian recycling complex and into the Garden of Love, which is presented as a space of transcendence.”

Installation view “Night in the Garden of Love” 2024. ©Aga Khan Museum, 2024. Photograph by Aly Manji.

Contemporary technology and nature are often pitted against one another, but Dawood asks visitors to see their kinship. “It was really to give people a transcendent experience and the ability to make these connections as much through the body as the mind,” he explained of the VR work. Dawood also highlights the links between music and plant life. “Lateef disliked the terms jazz and improvisation,” he said. “He had his own term called ‘autophysiopsychic’, which was about the transmission between audience and performers that activates your physical, mental, and spiritual faculties all at once. His ideas strongly connected to my childhood Sufi understanding of the garden as a metaphysical, transformative space.”

Nigerian-American artist Precious Okoyomon also taps into these garden-centric fascinations, creating immersive living artworks. The artist captured public attention with their 2022 Venice Biennale installation which featured mounds of earth, a water garden, a network of stone paths, and sugar cane within the crumbling Arsenale. Entitled “To See the Earth before the End of the World” the installation explored the colonization both of people and plants, taking inspiration from French writer and poet Édouard Glissant, who suggested that the sciences need poetry to thrive.

An underlying sense of threat often pervades Okoyomon’s work. In Venice, they planted the Japanese vine kudzu, which damages human-made structures such as home foundations and patios. In domestic life, these plants might be seen as troublesome or dangerous, but in the work, they are celebrated for their resilience. Meanwhile, in another installation last year, the artist filled a deconsecrated church, Sant’Andrea de Scaphis in Rome, with poisonous flowers and butterflies, which experienced their life cycle within the installation. The work—The Sun Eats Her Children—featured a bear sculpture, which moved between slumbering and wakeful states, and emitted a terrified scream as it came to consciousness. Music played a key role, with a melodic soundtrack by singer and cellist Kelsey Lu.

Precious Okoyomon, Earth Before the End of the World (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

In February 2024, Okoyomon will stage another living work at the Montaña de los Gatos in Parco Del Retiro in Madrid. The project, in collaboration with Fundación Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Madrid, will see the artist plant fig trees alongside a new sculpture, poems, and floral drawings. The work will draw parallels between poetry and plants and will feature music by turn-of-the-century composer Alexander Scriabin. “I keep burying my poems in the ground, and I think I’m planting real seeds,” the artist said when the exhibition was announced. “Everything disintegrates into the earth, and then the earth turns my words into everything that flows through the world, which is love.”

In another vein, British artist Mat Collishaw continues to explore his long-held fascination with fauna in “Petrichor” a new and major exhibition in Kew Gardens that underscores the tension between our human desire to care for plants and our attempts at dominating nature. “Within Kew Gardens, you immediately feel like you’re in nature and you can breathe peacefully again,” he said. “But far from being a natural environment, it is highly curated.”

Technology takes center stage in the exhibition: “Heterosis,” created using video game software, takes visitors on a journey through London’s National Gallery, devoid of human life and filled with swamp-like, abundant nature; “Alluvion”, a series of paintings inspired by 17th-century still lifes, are generated using AI; in “The Centrifugal Soul”, animated birds of paradise perform their famous courtship displays surrounded by eternally blooming flowers. Collishaw blurs binaries that understand technology as something inherently fake and nature as authentic.

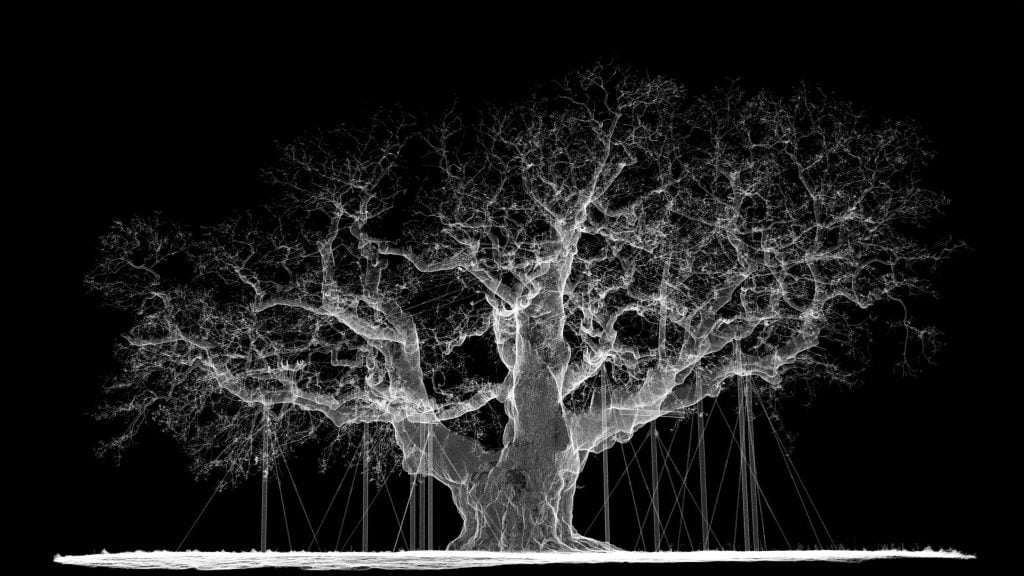

Mat Collishaw, Albion (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Kew Gardens.

“I think we’re reaching a point in history where the two things are coming together,” he said. “We can already see this in synthetic biology, where it’s possible to do gene editing and genetic synthesis. The ‘Alluvion’ paintings are a Frankenstein, fleur du mal hybrid. I see all these things being interconnected and I want to bring them together again as they’ve been pushed apart. We set up a polarity between what is natural and unnatural. But there is a lot of artifice in the natural world.”

He highlights the marketing ploys of brands that rely on punchy colors and instantly recognizable logos, which parallels the attention-grabbing features of fruits and plants of the natural world. Likewise, he sees a correspondence between the contemporary drive to edit and filter our appearances with the various plants that mimic insects and birds for camouflage or encouraging propagation.

Collishaw’s works resonate beyond the natural world. Albion is a grief-laden work that evokes the mighty power and tragic shackling of Sherwood Forest’s major oak, kept alive through human intervention. The laser-scanned, spectral video speaks to our drive to interfere in natural processes and was made in response to the U.K. Brexit referendum when a rose-tinted idea of “old England” was little more than an illusion. “It looks like this tortured soul,” he said. “This very noble dignified thing that just wants to die in peace. But because of its mythological significance to the tourist industry, its connection with Robin Hood, they’ve kept it alive with these steel rods that hold the branches. Chains inside of it that hold it up.”

Mat Collishaw, The Centrifugal Soul (detail 1) (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Kew Gardens. Photograph by Peter Mallet.

Like Dawood and Okoyomon, Collishaw hopes these works evoke an emotional response. His vibrant digital plants question the human drive that seeks ownership—even his role as an artist takes on a godlike quality, in building his worlds from scratch, before leaving them to algorithmic chance—and interrogate the neat categories we have created between human, natural, and technological. Viewers leaving the exhibition might question what humanity is doing to the natural world and why we see ourselves as so separate from it. “That would be an ideal,” he said. “And also, what is art and where is that going and what can it be. And how art, science, and nature interact and how to fuse them together.”