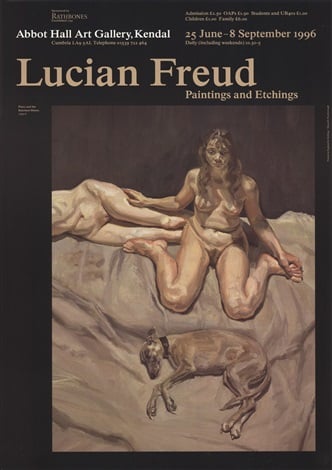

Lucian Freud Pluto and the Bateman Sisters(1996)

Photo: courtesy Dumbo Auctions, an affiliate of Rare Posters

Lucian Freud is one of the most well-known and influential painters of the 20th century. His expressionist style of portraiture is instantly recognizable, and over time he became a kind of living legend as he continued to paint and stage groundbreaking exhibitions right up to the end of his long life.

In spite of his fame, he remained an intensely private figure, shrouded in considerable mystery.

Born into a dynasty of era-shaping intellectuals such as Sigmund, Anna, Clement, Emma, and Matthew Freud, you could make the assumption that Lucian Freud was always destined for some kind of greatness—yet all the innate talent in the world won’t get you anywhere if you don’t apply it, and Freud wholeheartedly dedicated his life to his art.

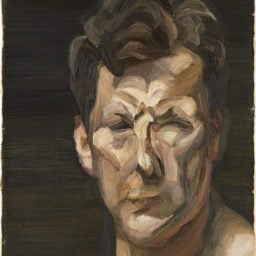

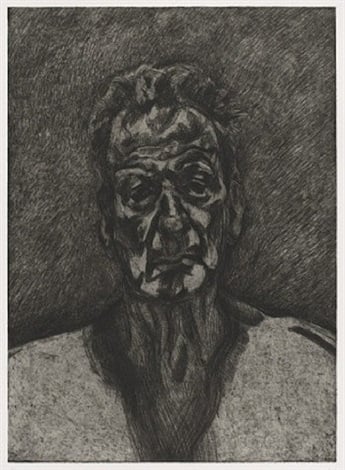

Lucian Freud Self Portrait(1996)

Photo: courtesy Art-on-paper

Freud was born in Berlin in 1922, and lived there until his family left Germany to escape Nazism in 1933. The family then settled in the pleasant, wealthy, North London area known as Swiss Cottage.

After he was expelled from school, Freud attended the Central School of Art in London and Cedric Morris’ East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in south east England. Freud then served as a merchant seaman for a short time, and on returning from service in 1942, he enrolled in Goldsmiths College where he began to pursue his career in earnest.

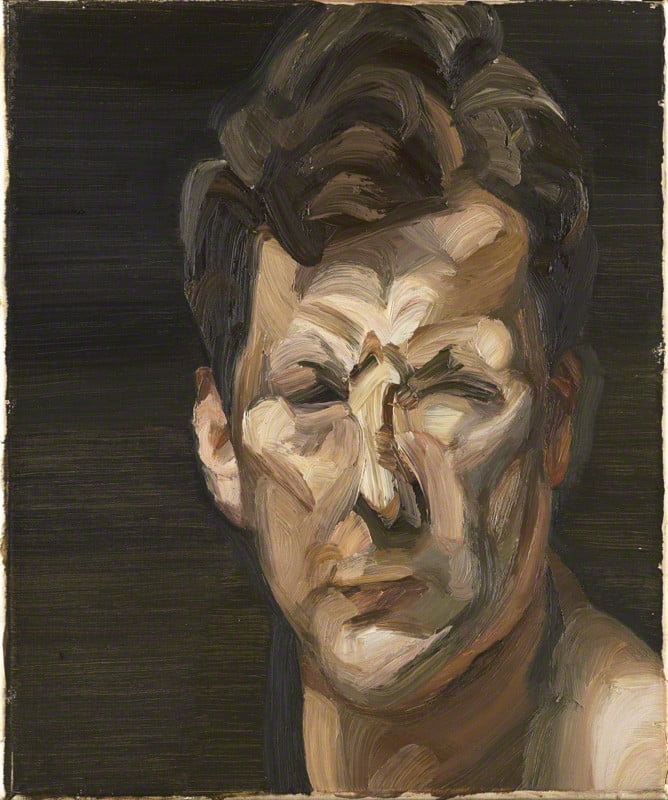

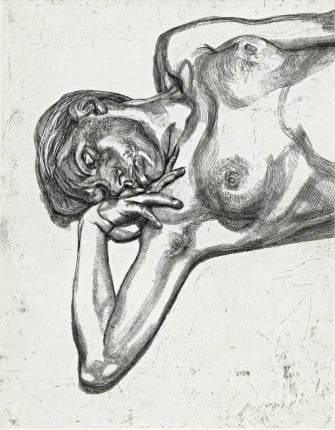

Lucian Freud, Head and Shoulders of a Girl (1990)

Photo: courtesy ARCHEUS / POST-MODERN

Following the publication of his first commission, illustrations for a book of poems, The Glass Tower by Nicholas Moore, Freud’s first exhibition “The Painter’s Room” took place in 1944 at Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery.

Freud’s early style was often referred to as expressionist or surreal, as his stark, contemplative figures seem visually skewed and exaggerated. As his painting technique evolved, his style transformed dramatically into the fleshy nudes and self-portraits most associated with him today.

For Freud this change was instinctive. His style was progressive yet accessible, and while his subject matter was challenging, the combination captured the imagination of the art-loving public.

“I never think about technique in anything, I think it holds you up,” he said an interview for an Omnibus documentary in 1984. “I think if things look wrong, or ugly in a way which actually clogs the information or feeling you’re trying to convey, then obviously you’re going about it the wrong way, but you have to take paint on trust.”

Freud was very private and almost never spoke to the press. The extremely rare Omnibus interview was conducted by Jake Auerbach, the son of Frank, as part of a documentary on his retrospective at the The Hayward Gallery that year.

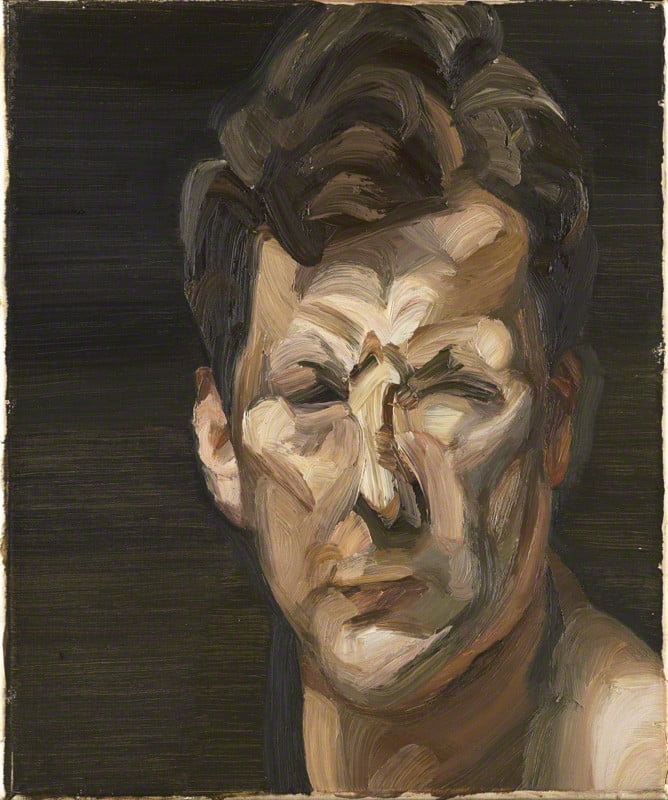

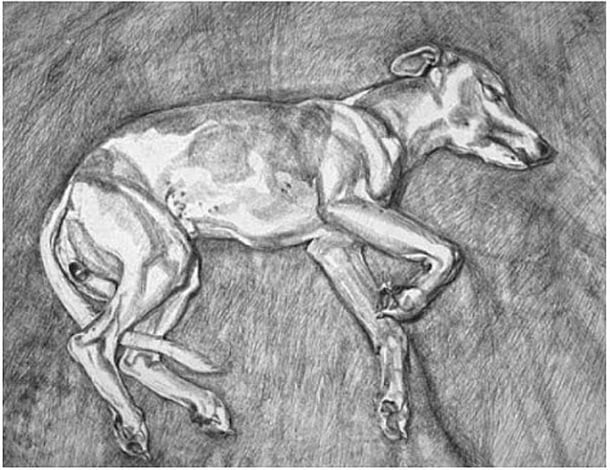

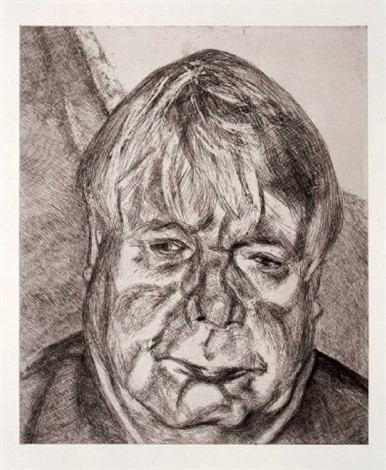

Lucian Freud Eli (2002)

Photo: courtesy ARCHEUS / POST-MODERN

Freud, along with his contemporaries in “The London School” like Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach, put making work ahead of everything else in his life. In their early days, supposedly the group of friends made so little money from their art that they used to argue vehemently over who would pay for dinner every time they went out. Nevertheless, they were confident in their future and their art, and never doubted that they would one day be very successful.

As Freud’s technique evolved, so did his subject of choice. His most infamous sitter is probably Sue Tilley, the curvaceous benefits officer he painted for the seminal work Benefits Officer Sleeping (1995), who went on to pose nude for him on a number of occasions. He also painted a select number of celebrities, including a portrait of a nude, pregnant Kate Moss in 2002, which later sold for £3 million (nearly $5 million). He also tattooed her lower back with two small swallows.

Lucian Freud Donegal Man (2007)

Photo: courtesy Acquavella Galleries

Controversially to some, he also painted his own children in the nude. Freud had many relationships in his life, and is rumored to have fathered up to 40 children—though the official number sits at fourteen.

Despite cultivating a large family, Freud continued to focus more on the studio than on his home life. In the year before his death in 2011, he mounted a large exhibition that focused on his studio at the Centre Pompidou, “Lucian Freud: L’Atelier,” which received rave reviews.

“As unrealistic as it sounds, I want each picture that I am working to be the only picture I am working on, to go a bit further, the only picture I have ever worked on, and to go even further, the only picture anyone has ever done.” Freud explained, in the short film Inside Job – Lucian Freud in the Studio, made by his long time assistant David Dawson.

The Freud we are able to glimpse was a wild, ferociously private man, that continued painting right up until his death. He and his contemporaries Auerbach and Bacon changed the face of British painting forever. With a singular dedication to perfecting his craft, he raised the bar for anyone who would choose to follow in his footsteps.