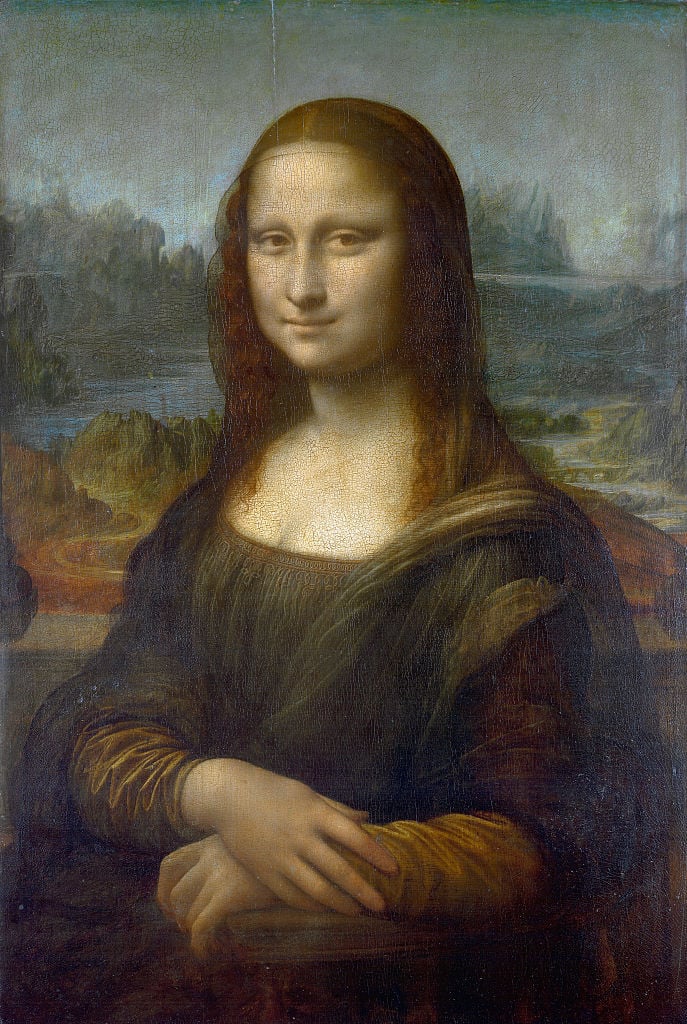

Art historians have tussled for ages over many aspects of what is arguably the world’s most famous painting: Leonardo’s Mona Lisa (ca. 1503–08). Who was the sitter? What does her smile mean? Is the background imagined or does it show a particular locale? If so, what landscape is depicted?

Now, a researcher has put forth a proposal for that last question that is supported by her twin areas of expertise. Ann Pizzorusso has credentials both as an art historian and as a geologist, and she argues that the rock formations in the painting closely match those in the area of the small city of Lecco, on the shore of Lake Como in in northern Italy’s Lombardi region.

“I am very gratified that I am able to shed light on Leonardo’s accomplishments as a geologist,” said Pizzorusso in an email. “He had a great respect for nature and depicted it accurately in every painting. For him, unlike other artists, he valued the landscape as much as the figures.”

Pizzorusso claims to have identified not one, not two, but three features in the painting and pegged them to this locale. First, there’s the body of water in the painting. She says it’s Lake Garlate, which Leonardo is known to have visited. Second, there the 14th-century Azzone Visconti bridge. But third, and most significant, there are the rock formations in the Alps overlooking the area, which line up very closely with some of the rock formations just over the right shoulder of the sitter, Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo (the painting is sometimes called La Gioconda by the Italians and La Joconde by the French).

Some art historians argue that the background is based in fantasy, while others have argued for specific locations, such as the town of Bobbio or the province of Arrezzo, but those arguments were based solely on the bridge and a road, Pizzorusso pointed out. What’s more, neither of those locales has a lake, as Lecco does. The colors of the rock formations there also match the hues Leonardo used to paint his rocks, she said.

A geologist and writer on Leonardo says she has discovered the area that inspired the background in the Mona Lisa. Courtesy Ann Pizzorusso.

“They all talk about the bridge and nobody talks about the geology,” she told the Guardian, adding that the art history and geology fields come together all too seldom: “Geologists don’t look at paintings and art historians don’t look at geology,” she said.

Pizzorusso, according to her website, worked in various facets of geology, including oil drilling, gem hunting, and environmental cleanup projects. But she then fell in love with Italian Renaissance art and earned a master’s degree in the subject, and since then has brought the two fascinations together in her writing. Living between Italy and New York, she playfully pointed out that she hopes her publications “have a golden nugget of Earthly information on every page.” She has published a few books on Leonardo alone.

No fewer than two prominent figures have weighed in to support Pizzorusso’s argument in the Guardian. Michael Daley, director of the British nonprofit ArtWatch U.K., which aims to enforce high standards in art conservation, called her theory compelling, while Jacques Franck, who was once a Leonardo consultant for the Louvre, said, “I don’t doubt for one second that Pizzorusso is right in her theory.”