Museums & Institutions

A Former Gas Station in Berlin Has Been Revamped Into a Museum Dedicated to the Celebrated Weimar Artist George Grosz

The German artist captured the harsh realities of life in Berlin in vivid color.

The German artist captured the harsh realities of life in Berlin in vivid color.

Hili Perlson

“The ducks had to go,” dealer and collector Juerg Judin told me, pointing at the small, now duck-free pond he had installed in the backyard of his old Berlin residence, a repurposed gas station from the 1950s. His former private home, which also became the habitat of a few exotic geese, ducks, and birds, has been recently handed over to a nonprofit association that will run an institution there over the next five years, the new Kleine Grosz Museum.

This privately funded venue, which opens to the public on Saturday, May 14, will be dedicated to the Berlin-born political artist George Grosz, a fixture of modern art history in Germany.

The name, which translates to the Little Grosz Museum, is a pun—Grosz sounds like the German word for big. It’s also a cheeky reference to the intimacy of the space, which is spread across two small levels of the revamped Shell station.

Exterior view of the Kleine Grosz Museum © Annette Kisling.

Despite the size, the modernist location has been expertly outfitted to provide museum-standard climate conditions. “That’s a must if we ever want to exhibit loans from institutional collections,” curator Pay Matthias Karstens said. (That’s also the reason why the exotic fauna had to be relocated.) Until the museum establishes a two-year backlog of climate control with which to approach institutions to obtain loans, the works on view will all stem from private collections—including Judin’s—and from the holdings of the Grosz estate.

Through painting and drawing, Grosz, who was active in the early 1900s until his death in 1959, captured the social realities of Berlin without euphemism. His caricature-like figuration has established him as one of the German capital’s most well-known artists from that last century; and yet, the Kleine Grosz Museum is the first institution dedicated to his oeuvre. This private initiative probably would not have happened if it weren’t for Ralph Jentsch, the managing director of the estate and the editor of Grosz’s forthcoming catalogue raisonné. The museum’s future beyond its initial five-year run will depend on its success in drawing in visitors and accruing financial support from additional funders.

Inside view of the museum. Photo: Hanna Seibel

The museum’s ground floor houses a permanent collection that provides a chronological overview of the artist’s career, highlighting major periods of work during the Weimar years as well as his time in the U.S. It outlines a narrative that not only follows the sharp-eyed artist and draftsman’s sensibilities but also the horrors of the first half of the 20th century and the economic boom of the post-war years.

In 1928, Grosz created the stage set and costume design for Erwin Piscator’s staging of the dark comedic story Soldat Schwejk, and the watercolors he created as studies are a wonderful highlight of the exhibition in Berlin. Like much of the museum, it conjures a Berliner story: The German theater director’s famed Piscator-Bühne was just around the corner from where the museum is located, in the neighborhood of Schöneberg.

The upper level of the museum is dedicated to changing exhibitions; there will be two per year, ten in total for the museum’s already-secured duration. The first one, titled “Gross Before Grosz,” focuses on the artist’s very early years: already as a teenager, the young country boy named Georg Ehrenfried Gross exhibited a great talent as an illustrator. After the current show closes in September, the second exhibition set to open in November will explore Grosz’s 1922 travels to Soviet Russia where he met Lenin.

George Grosz Nächtlicher Überfall (1912). © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

A selection of drawings from the current exhibition dating to 1904, when the artist was only 11 years old, are the first works visitors will encounter here. One drawing on a torn piece of paper features four anthropomorphized frogs. “You see very early on that someone is trying to master the technique, who has the ambition to become a real artist,” Karstens, the show curator, said. “Many of the motifs we see later are already present here.”

This early work is prominently signed G. Gross. Key to the artist’s ambition was to be recognizable, successful, and a brand—to do that, his birth name was simply too common in Germany at the time. In 1906, aged only 13, he already began experimenting with signing his creations under the name Grosz. It is only much later on during World War I that the artist became politicized and radicalized, developing anti-German sentiments that prompted him to change his first name as well to its anglicized version, George.

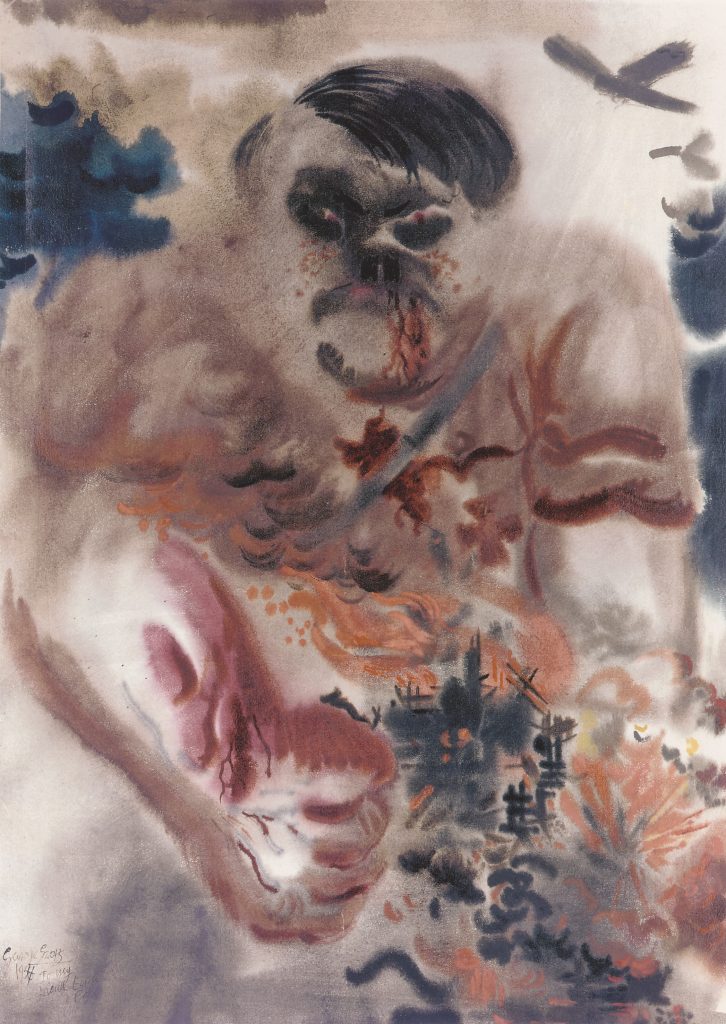

George Grosz Die Bedrohung (The Menace), (1934). © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Alongside works created as a student in Dresden, the temporary exhibition also includes works from his early years in Berlin. Interestingly, these show a certain fear of the big city and its colorful characters. Human figures suddenly begin to appear in works such as Nächtlicher Überfall (translated: nighttime robbery) and Selbstmord (the German world for suicide), or a drawing of a derelict bar (all from 1912), which show scenes of violence and despair. “Moving in the city by day and night, he drew what he saw,” Jentsch said. “Grosz is not a caricaturist, he’s an observer.”

The artist’s canny observations, which Grosz is most well-known for, continue in the permanent exhibition on the ground level. Works in the chronological show include output from the 1950s, after Grosz and his family had moved back to Germany from the U.S. Never having reached the financial success he had hoped for on the other side of the Atlantic, a self-portrait shows the artist in his studio, bitter and defeated. The canvases around him are in disarray, and are punctured by a bean-shaped hollow that also features on the artist’s forehead. In his later years, George Grosz, one of the artists most closely associated with Berlin’s history, considered himself a failure.

Despite his tumultuous career, what he depicted ended up being occasionally prophetic. A watercolor from 1934, done when Grosz was already living in the U.S., called the Menace, shows Hitler as a murderous monster. “Created three years before Guernica,” Jentsch pointed out, “the work already anticipates what Hitler would soon become responsible for.”

Das kleine Grosz Museum opens to the public on May 14.