Artists

‘The More Repellent You Are, the More Attractive You Become’: George Condo on Contemporary Mythmaking

The artist opens up about his minimalist turn at the Deste Foundation, and distancing himself from Kanye West.

The artist opens up about his minimalist turn at the Deste Foundation, and distancing himself from Kanye West.

Naomi Rea

The ancient Greeks had two words to describe the essence of time: chronos, the relentless, linear progression of history, and kairos, the profound, unfolding moment that breathes life into the present.

As I arrived at the sun-drenched opening of George Condo’s latest exhibition, on the Greek island of Hydra, these concepts prepared me to meet an artist whose works skip seamlessly between the past and the present. Condo approaches art like a producer, remixing and sampling the annals of art history. His paintings of what he calls “artificial realism” emerge from a deep study of the old masters and classical music, mashing up the structured schematics of representational painting with the improvisational spirit of jazz.

Whether you like it or not, the result is a distinctive vision, manifest in his human figures with pinched faces and gnashing teeth. With their market prices punching in at as much as $2 million primary and up to $6.9 million at auction, they lend unmistakable wall power to any setting.

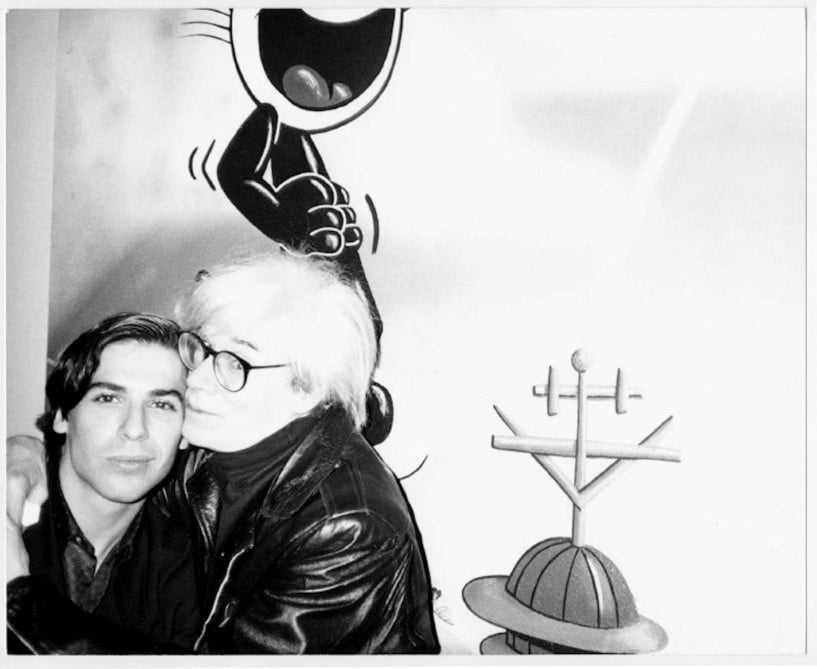

George Condo and Andy Warhol, 1986. Courtesy Warhol Foundation.

For such a titan of contemporary art, Condo has a surprisingly bashful demeanor, red-cheeked in a simple polo shirt amid the sweltering summer heat. This unassuming appearance belies a storied past orbiting the likes of Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Keith Haring, and forging literary friendships with icons such as William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Salman Rushdie.

The intimate exhibition opening at the Deste Foundation, a passion project of Greek-Cypriot billionaire Dakis Joannou, also eschewed the grandiosity you might expect at major private foundations in Paris and New York. Instead, it offered a personal touch, with Condo himself mingling among friends and art world luminaries, including gallerists Thaddaeus Ropac and Eva Presenhuber, curators Massimiliano Gioni and Cecilia Alemani, and the septuagenarian photographer Martin Parr, who was hobbling around capturing the activity at the former slaughterhouse on a coastal hillside.

Inside the show are diminutive paintings, which Condo has encased in wide, polychromatic minimalist frames, their colors evoking the once-vibrant hues of the Parthenon marbles. These small canvases, alongside head sculptures and one larger sculpture (The Triumph of Insanity), reveal the protagonists of Condo’s own mythology—”The Mad and the Lonely”—captured in shifting, bacchanalian expressions.

As the sun set, casting a golden glow over the island, I mused on the entangled threads of chronos and kairos within Condo’s art. Our conversation, which follows, looks back on his impressive career and offers a glimpse into his relentless forward motion, with a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris on the horizon for October 2025.

Installation view, “George Condo : The Mad and the Lonely,” DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. ©George Condo. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

I haven’t seen many of your shows outside of a white cube environment or auction houses. What was it like thinking about a show for this very specific environment?

First of all, I’d never been to Hydra and so we had plans of the space, but we had no idea how small it was. If you think about the boxes like musical keys, you would think they’re major keys, and that the paintings that are locked inside of those boxes are more like minor keys. And so there was this sort of conflation of major, minor, positive, negative, which I liked.

So you thought about the presentation of the work as part of this exhibition.

The paintings themselves reflect the internal emotional aspects of our everyday life. They may not be portraits of anybody in particular. But they’re portraits of emotional states of mind. And most of the time they’re relatively sad, mad, and lonely. And so that’s where the title of the show came from.

But then once I thought about the way of presenting it in Greece and thinking about how to deal with proportions—because the Greeks were the masters of proportion—and I thought everything has to be proportionate to the space. So I feel like, given the proportionate aspect of the presentation of the work within the space, that would be very uplifting to some degree, because it would be a new way of seeing the work. Ellsworth Kelly would never put a figurative painting on one of his pieces, nor would Donald Judd. And a traditional oil painter would never put his work in a minimalist encasement, so it was a contradiction and at the same time a conflation of the two concepts at one time.

It almost feels sacrilegious.

The paintings are made up of a million different interchangeable parts from art history. And one of the languages in art history that I would say that I never really delved into was minimalism. And so this was a way of combining minimalism and figuration in this exhibition. It was about the idea of the interchangeability of languages in painting and the idea of the multiple emotions that run through any single person’s mind, but also that internalization of their emotions being seen on the surface of the painting itself.

George Condo, The Mad (2024). Installation view, “George Condo : The Mad and the Lonely,” DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. ©George Condo. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

How often do you work in that kind of diminutive scale?

Well, I’ve always loved painting small paintings. I like small paintings a lot. Like in museums, if you look at Vermeer or painters from the past, notice how small their paintings are. They put big frames on them to make them look bigger, but in fact, the paintings are quite small, other than the View of Delft and maybe the one that’s in Edinburgh [Christ in the House of Martha and Mary].

But for the most part they’re quite small. I like detail. I’m very into detail and I’m very into incorporating as many different languages as possible into a single painting and creating one iconic figure that would represent all those different periods of time.

Are all of the works in the show from your personal collection or were there any loans from elsewhere?

Oh no, they were all personal paintings. I never signed any of them, thankfully. So that way they didn’t have signatures on them in the middle of the boxes. They were just my personal collection. They were from ’89, ’92, ‘97, 2005 … whatever paintings worked the best in concert with one another was basically the way I went about choosing what I wanted to put into the boxes. I made multiple exchanges. We had painted boxes that were just our own made out of cardboard, and I kept switching them around until I finally found what I felt like made the most sense in terms of my sensibility.

Installation view, “George Condo: The Mad and the Lonely,” DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. (June 18—October 31, 2024). ©George Condo; Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

You talked a little bit in your discussion with Massimiliano Gioni the other night about your beginnings and your entry into the New York art world, and you mentioned gallerist Monika Sprüth. How important was she to your introduction to the art world and the development of your career?

Very important. When I left New York for Europe for the very first time, it was because a few German artists had been in New York in the early ‘80s and they said: Nobody in America is going to understand your work critically. They’re not going to take it from the way they think in a sort of let’s call it a linear, chronological way. But in Europe, you would probably be much more appreciated because an American delving into European masters will seem, again, more sacrilegious than it is in America.

In that same discussion, I was talking about the idea of Marcel Duchamp and his found objects. I wanted to create a kind of simulated found object in the sense that it looks as if it might have been painted 400 years ago, but given the subject, it couldn’t have been. So there was that aspect of Dada in painting what I call “fake old masters” because they weren’t real old master paintings, but they were painted with the same techniques.

I think it liberated a generation of younger painters who went to Yale and were taught traditional means of painting, but then the subject matter was also very traditional. To transpose those traditional matters of painting into a contemporary subject matter was something that I think I was able to allow them to do by saying, You can paint like a 17th– or 18th–century master, you just have to have something new to say.

Installation view, “George Condo : The Mad and the Lonely,” DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. ©George Condo. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

Do you feel like Americans get your work now?

Yes, now they do. But I think it’s thanks to the generation that’s younger than me, like Cecily Brown and John Currin and Glenn Brown, and even Anna Weyant—all of those artists that are starting to use these traditional methods of painting and creating contemporary subject matter, using old-fashioned techniques. At the time when I was using old–fashioned techniques, let’s call them antiquated… I think it was an insult, critically, in comparison to what was happening in the early 1980s.

Obviously you are now a star. Do you recall a moment where you realized that you’d made it?

Well, I felt it was when artists started to recognize my work. When I was accepted by the artists, that’s when I felt that my career as a painter was taking off.

Then when I showed with the beloved Barbara Gladstone, our friend who recently passed, we did a show together with Pat Hearn in ‘84, and Eli Broad bought some of the work and some of the big collectors were coming in and starting to buy my work. I didn’t know them, but they were looking for what was happening. Don and Mera Rubell were some of the first collectors. They’re always on the first tier of looking for what’s young, what’s out there.

And when you’re 23 or 24 years old and you’re a painter, when I was coming up as an artist, if you were not somewhat famous by the time you were 24, you were finished. I think now you could be 35 and you can still have a chance, but in my era if you didn’t get it by then, you didn’t get it. So there was a rush to make something special and radical and new and somewhat timeless that could exist and stay there forever.

Installation view, “George Condo: The Mad and the Lonely,” DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. (June 18—October 31, 2024). ©George Condo; Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

You often talk about your work in musical terms. Thinking about art history and the idea of remixing or sampling in music and how that’s kind of present in your work, is that concept more recognizable to a younger generation today who sees your work?

I once thought about the television and that you could change the channel. You could be in the middle of a documentary on the Second World War, and if you changed the channel from five to six, it was baby diapers. And if you changed the channel to the next one, it was some kind of a cartoon.

And I thought painting can be like television. This is before cellphones and computers of course. Also there were fewer channels. I thought this sort of way of changing channels in a painting was very similar to sampling, which is what has been happening in hip hop.

Have you noticed a change in how people view your work?

Generally speaking, most artists, Jasper Johns would be one of them, will say: Everybody loves my early work. Nobody likes my late work. Andy Warhol: Everybody loves my early work. Nobody loves my late work. And in my case, nobody loves my early work. Everybody likes my new paintings, and I’ve heard it so many times. Every year they say: These are the best paintings you ever made.

And I think, well, when I have the retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris in ’25, we’re gonna show works from 1975 when I still lived at home with my parents and I didn’t even know there was such a thing as the art world. I like the work that has got that pure aspect of simply believing in art and believing that art is a language that is subjective to the viewer. The art doesn’t tell the viewer what to think. The viewer thinks what they think the art is telling them. So in other words, it’s possible that an artwork can decide whether the viewer is good or bad. It’s not the other way around.

Installation view, “George Condo: The Mad and the Lonely,” DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. (June 18—October 31, 2024). ©George Condo; Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

Thinking in terms of music and hit songs, what do you identify as your number one hit series?

I would say the early paintings from the early ‘80s. The first foray into painting in this traditional manner, like the Madonna that I did in ‘82, and the paintings from ‘84 were a full-on hit series of clowns and things that represented a sort of transgressive concept, what would be anti-high art. And then I think the more improvisational work, which came between ‘85 and, say, ‘95. I think it’s a bit more complicated for people because it’s like listening to John Coltrane and being able to handle it because he might take a song, My Favorite Things, and everybody knows it from Mary Poppins or whatever it came from [The Sound of Music], and he played it different from the first time he recorded it to the end of his life. And so every single time I do a portrait, I paint it different. I take it as themes and variations on a motif.

So if someone like Miles Davis, when he plays Summertime, you know he’s going to play it his own way, even though you’re going to recognize the tune, the improvisation on that tune will be Miles Davis and it’ll be distinctly Miles Davis. And nobody will ever have sounded like Miles before Miles.

And so I think what I like to achieve as an artist would be that they’re recognizable motifs, the human beings, but their existence in the painting is in such a way that you’re never gonna see it any other way than the way I do it.

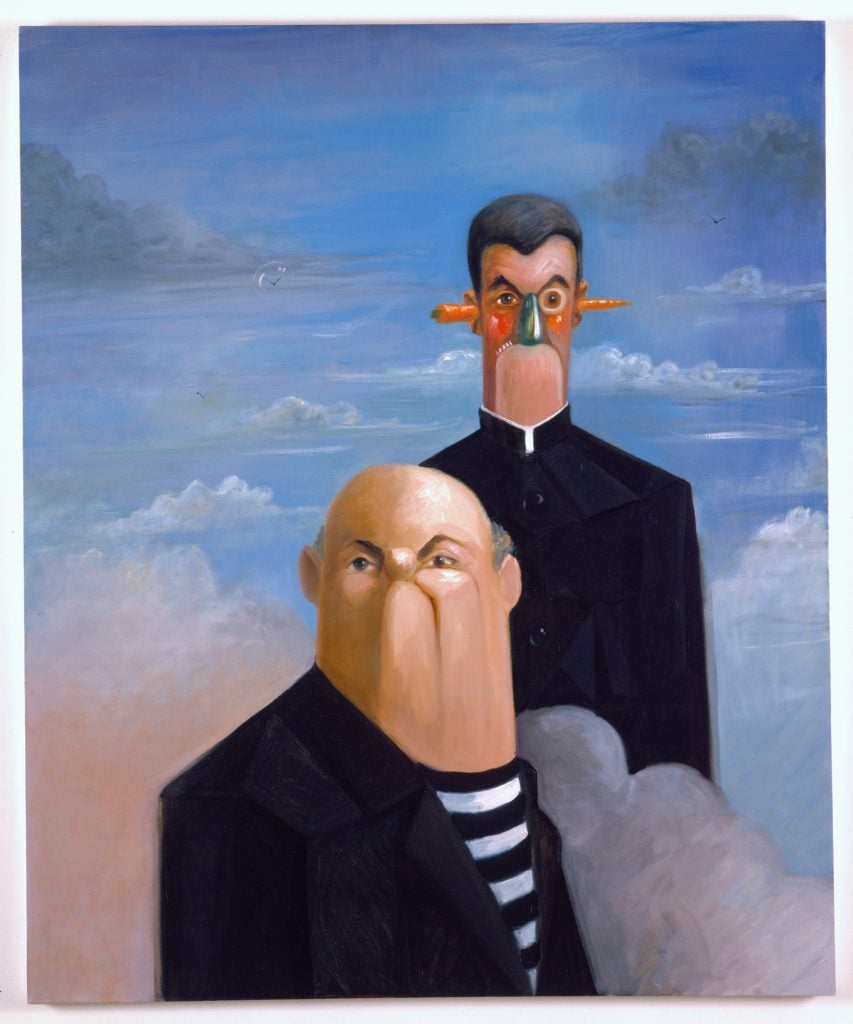

George Condo, Portait of Dakis Joannou and Maurizio Cattelan II (2006).©George Condo, courtesy of the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art.

I noticed in Dakis Joannou’s house in Athens, he’s got two paintings that you did of him and Maurizio Cattelan hanging in the living room. How do you deal with requests for portraits as a painter, whenever you are doing your own thing and you’re improvising in your own way, and you’re letting the painting take you where it wants to go, rather than necessarily where your subject wants you to go with it?

That’s a good one. Maurizio came to me and he said that he wanted to introduce me to Dakis. So Maurizio said, We want to look like your paintings. We don’t want to look like us. We wanna look like one of your paintings. And so I said, Okay, that makes it a lot easier because I don’t want to sit there and make an academic study of Dakis and Maurizio. They wanted to look like a George Condo painting. And so I never take commissions. Really rarely. But working on the portraits of Maurizio and Dakis was really special because I got to paint them so that they were them, but they were them and me at the same time.

I brought my partner to see the show. And he’s interested in art but doesn’t come from art, and when I said, We’re going to go see a George Condo show, he said, Oh, I know George Condo. Because he listens to hip hop and he recognizes your name from a couple of Westside Gunn songs. I found that so amusing as an entry point, but I guess it is for many people because you’ve become a figure in hip hop, haven’t you?

Yeah. Well, for much of the hip hop audience, when I did the Kanye West cover back in 2011, it was an introduction to an audience that was not tuned into painting.

And the thing that made it radical and got it banned was the idea that if you paint in the language of a child a sophisticated concept, which was a biracial couple having sex on an album cover, but it was painted in the language of cartoon…

I think where it blew fuses was that if I had painted it very representational, it would’ve been so boring and it wouldn’t have been at all in concert with the music. The artists around Kanye and the people that he worked with, Jay-Z and now Travis Scott and I have done collaborations together, and a lot of the hip hoppers like Lil Baby and Pop Smoke or Rick Ross, they all love my work because they like the idea that I don’t care what people think of my art, and they can use whatever language they want in their songs and they don’t care how offensive it is. And they think to a certain degree what we can do is be offensive in a way that is acceptable somehow. So there’s another kind of contradictory paradigm in that idea of being extremely offensive—or the more repellent you are, the more attractive you become.

You mentioned being banned—I remember the work was pixelated for iTunes and for mass consumption. How did you feel about that as an artist?

I thought it was cool. I liked it. It made it even more apparent that you wanted to see what was behind the pixelation. And in Europe when they released the album, they released it without the pixelated covers. So the idea that it was pixelated meant that it was like John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s brown paper bag.

If you think of how many things you can do that could be banned, it’s not easy to get banned. It’s quite an achievement, in fact, to be banned. So I didn’t mind as an artist because I knew the painting existed in its absolute form. The mutated form was strictly for Walmart and Apple and these kind of corporate environments.

I’ve been listening to some of these songs, and your name is dropped in hip hop and in trap music here and there, and it’s often in the context of flex culture. It’s like: I have enough money to have a George Condo on my wall. It’s a little reductive in some sense, like your name is now synonymous with a lot of dollar signs. How do you feel about that?

The thing is, when you’re brought up in a very, let’s just call it lower income environment, and you make it in hip hop, the first thing to do is buy a massive bling and to wear as many chains as you can possibly wear.

I grew up in a family that was not poor, my father was a college professor and my mother was a registered nurse, but my dad forced us, my brother and I, to work in factories and to work in horrible jobs when we were 15, 16, and 17. And I spent my whole life laboring in these terrible jobs that you can’t imagine. Like working in factories and you see people with fingers missing… I made $1.40 an hour back then, and when I was delivering newspapers, I made 25 cents. And when I was mowing lawns, I made 25 bucks per lawn. So when you finally make some money off of painting, you feel gratified that your work is worth something to other people.

In any case, I think that that is where the empathetic relationship between myself and the hip hoppers comes from—we don’t come from wealth and I think when you finally make your first dollar from being a rapper, you somehow want to express it in a way. You’re proud of the money that you make because we had to create our own kind of wealth in whatever spectrum of wealth, you could call it. So as far as they’re concerned, ‘a Condo costs more than your condo’ might mean, you know, $600,000 for a condo and a painting costs $700,000, something like that or more, who knows?

I think a little more these days.

But I don’t think the market ever dictates what a good hip hopper does, nor do I think it dictates what the great painter will do.

I just think you have to be glad, you have to be happy that you make money from what you really want to do in life.

Installation view, “George Condo: The Mad and the Lonely,” DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. (June 18—October 31, 2024). ©George Condo; Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

What was it like working with Kanye West and those guys?

When I remember when I met 2chainz, Lil Wayne, and A$AP Rocky, and they introduced themselves so quickly that I wasn’t sure who was who. And they all had so many chains. I was like, Which one’s two chains? I wasn’t sure who was who until I saw them later in music videos and I didn’t even know who Kanye West was when he asked me to do the record cover. I had to ask my daughters, I said, who is this guy? And they told me, Oh, he’s a really big rap star, Dad.

And then, as we followed the trajectory of Kanye West, now we realized that he’s gone to a completely different place. He is no longer the Kanye West I knew, let’s put it that way. I’m sure he is still a creative genius, but I don’t align myself with his political position in life. I’m against the hate speech. I don’t like the MAGA thing. I don’t like any of that business. And I think his admiration for it is not necessarily naive. I think it’s intentional.

George Condo, The Triumph of Insanity (2008). Installation view, “George Condo : The Mad and the Lonely,” DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra. ©George Condo. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

I hear you. I guess we’ll see how Kanye’s story unfolds over time, and where that sits in history in the long run. But what about you, how do you see yourself and your place in art history? Did your change in galleries in 2020 have to do with you thinking about your legacy?

A change of galleries is kind of something that happens every 10 or 11 years. It seemed to me, you know, over a 40-year period of being in galleries, it seemed like I was with a gallery for 10 years or 11 years and then all of a sudden it changed for one reason or another, even though I’m still friends with any gallery I ever worked with.

It was time for a change, and it had to do with the artists that they show. I wanted to be closer to the artists that were being represented by Hauser and Wirth. Like the [Philip] Guston and [Arshile] Gorky estates or Rashid [Johnson], or younger artists like Avery Singer. I like those painters’ works and I like being in a gallery that shows painters whose works I really like.

So it really had nothing to do with legacy. I think the only thing you can possibly do to affect your legacy is to just keep being forward–moving as a creator. And your next paintings will be a surprise, you hope. You don’t want to be repetitive. You don’t want to say, Oh, I got that one right. So I think I’ll just do it over and over again. You want something new every time.

I guess that’s why I’m really happy with Hydra because it was totally new for me. And I think it was new for the audience as well, to go there and see something like that and say, Hmm, I don’t believe I’ve seen this combination of minimalism and traditional painting before. And then these kind of Greek mythological figures that are in the show. I thought up my own myths. So I think the idea of an artist creating their own myths and their own mythological lexicon, whatever you wanna call it: Like the way Greek myths last forever. You hope that your own myth will go on forever.