Art & Exhibitions

These Newly Restored Films Reveal a Rare Glimpse Into Warhol’s Silver Factory

Post-restoration, the films by Gerard Malanga are getting their world premiere in Pittsburgh.

Gerard Malanga spent most of the 1960s working with Andy Warhol at his New York Factory. He collaborated with the Pop artist on his silkscreens, shot and starred in his films, and danced with the Velvet Underground, undertaking both administrative and Superstar duties. As a photographer, Malanga also kept his camera running, capturing the creative and at times playful scene that surrounded Warhol.

“I just felt it was important to at least document the milieu that I was a part of,” he recalled in 2009, “because what was happening was important.”

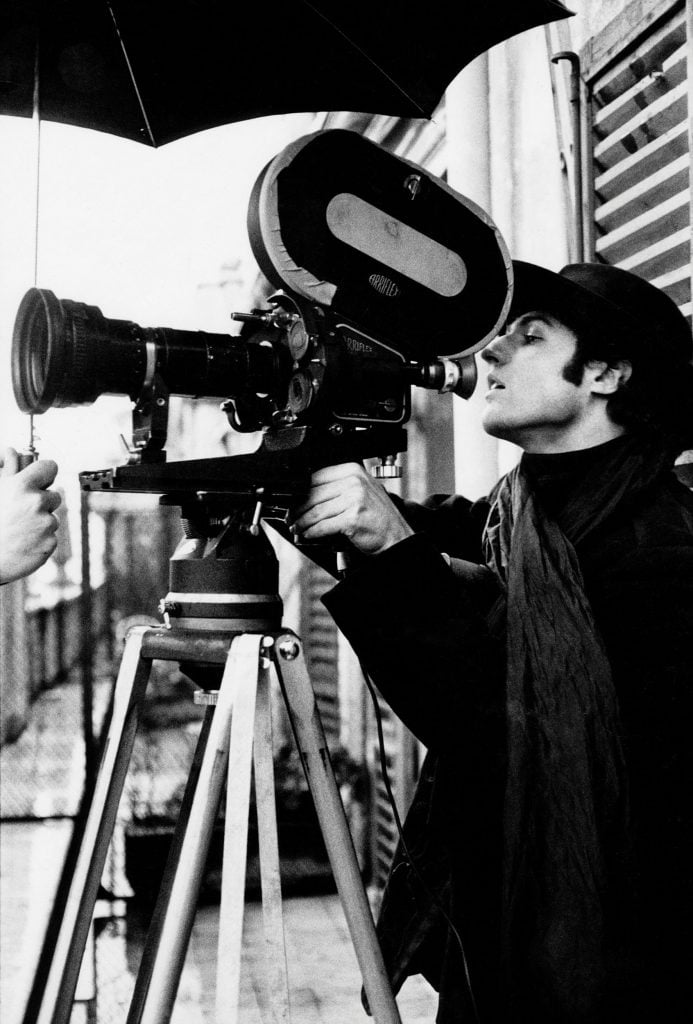

Gerard Malanga. Photo: © Gerard Malanga. Courtesy The Waverly Press.

Now, three films by Malanga, some long unseen, have been revisited and restored under the auspices of Waverly Press. The project coincides with the making of a forthcoming monograph, Gerard Malanga: Secret Cinema, authored by the Trust’s director of galleries and public art, Anastasia James. In a presentation by the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust on December 14, the 16mm works, newly transferred to 4K, will have their world premiere at the Harris Theater in Pittsburgh, Warhol’s birthplace.

Collaborating with Malanga for more than a decade, James told me over email, “has underscored the urgency of preserving these films, which capture the raw energy and complexity of the 1960s avant-garde. I can’t understate how integral Gerard’s films are to a fuller understanding of Warhol’s legacy and restoring them and presenting them ensures that they are accessible to both scholars and a new generation of viewers.”

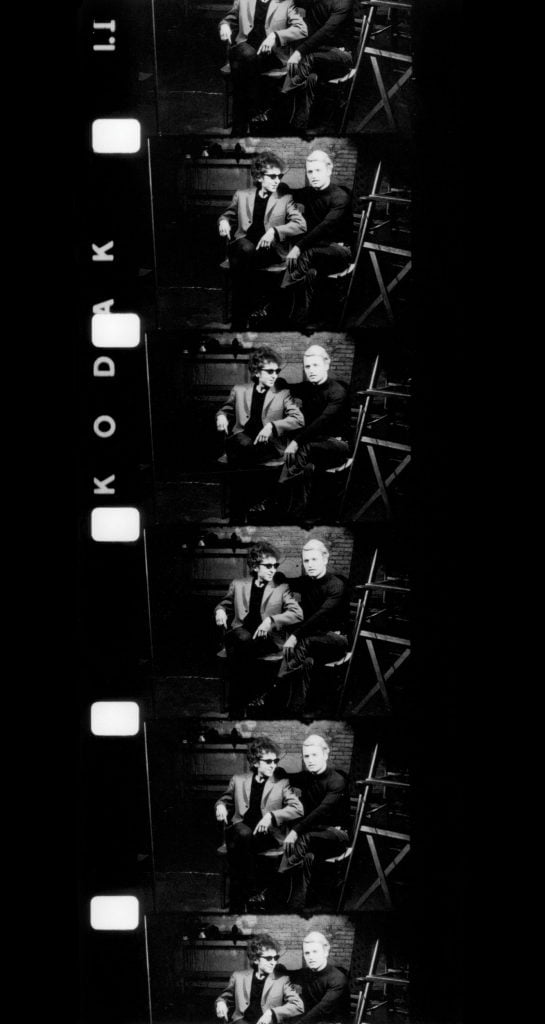

Gerard Malanga and Andy Warhol. Photo: © Gerard Malanga. Courtesy The Waverly Press.

Malanga joined Warhol’s studio in 1963, where he would become instrumental as the artist developed works including Triple Elvis (1963), his “Flowers” series (1964), and his collection of Screen Tests, which featured famous names and faces. Though often remembered as Warhol’s “assistant,” his actual role in the Factory bled beyond that. “His influence,” James stressed, “was indispensable in shaping the Factory’s aesthetic and intellectual ethos.”

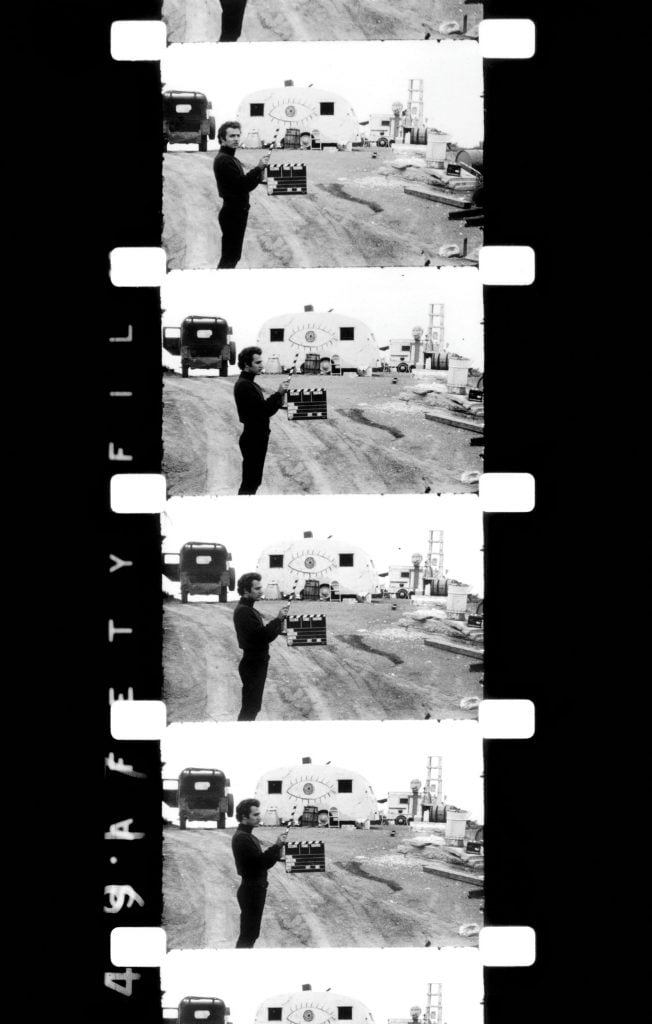

Evidence is in the three newly restored films, which chronicle Malanga’s work at the studio. Among them, Film Notebooks, 1964–1970, previously presented at the 2005 Vienna International Film Festival, compiles a trove of footage that offers a behind-the-scenes peek at the Factory goings-on. It includes views of a performance by the Velvet Underground at Paraphernalia, Edie Sedgwick applying makeup, Warhol filming Sedgwick applying said makeup, and Bob Dylan and Salvador Dalí sitting for their Screen Tests.

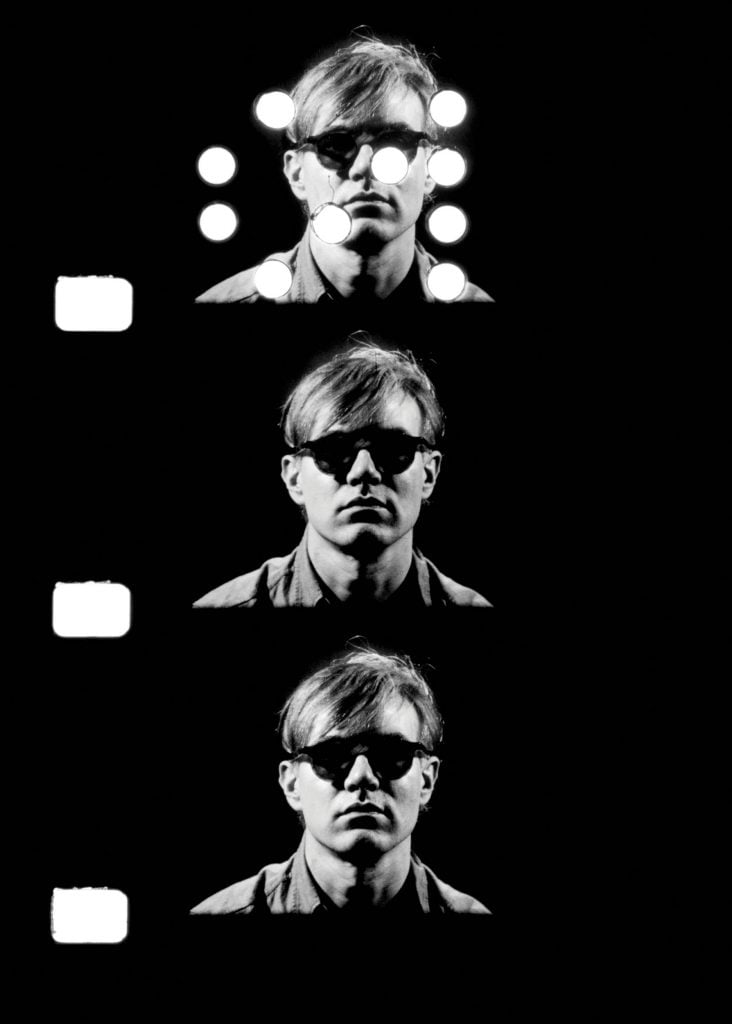

Gerard Malanga, Film Notebooks, 1964–1970. Photo: © Gerard Malanga. Courtesy The Waverly Press.

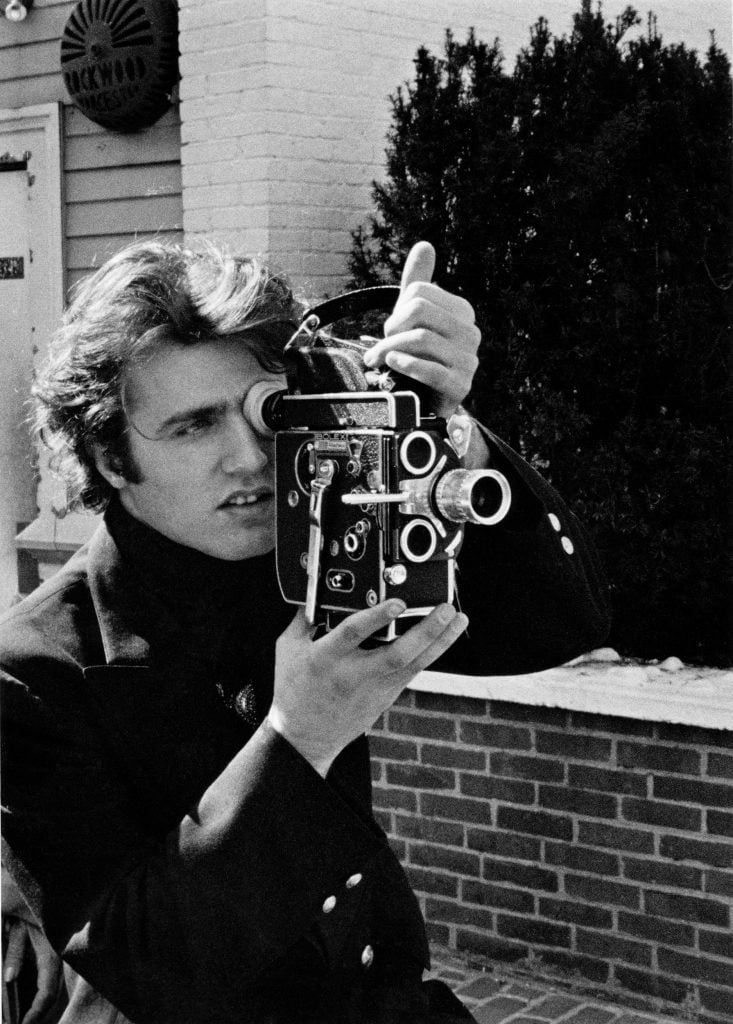

The Filmmaker Records a Portion of His Life in the Month of August, 1968 taps that same vein of documentary. As it says on the tin, the 15-minute film serves as Malanga’s visual diary, which he recorded using an 8mm Keystone camera gifted to him by artist and filmmaker Marie Menken. Warhol shows up, as do New York avant-gardists including Marian Zazeela and La Monte Young.

Perhaps the most remarkable of the trio of films is Andy Warhol: Portraits of the Artist as a Young Man (1964), in which the Pop artist himself becomes subject of a Screen Test. Over 20 minutes, Warhol is filmed in close-up, under various lighting experiments, with and without his trademark sunglasses, his vulnerability on rare display.

“I made this series of film portraits of Andy Warhol at the Silver Factory in 1964 and 1965 as seven individual three-minute sequences, on different days,” Malanga said in a statement about Portraits. “It’s basically mimicking the Screen Tests that we were doing at the time.”

To James, this particular film is unique for its unprecedented view of a famously elusive character: “Here, Warhol slips in and out of a constructed persona, revealing the delicate dance between presence and image, artist and icon.” She describes it as “among the most revealing and intimate documents of the artist I have ever seen.”

Gerard Malanga. Photo: © Gerard Malanga. Courtesy The Waverly Press.

According to James, Malanga’s films are scattered across personal and institutional collections, with some of them remaining in his own archive. Yet more reels were unearthed during the research process for the Malanga monograph.

Over many months, experts from “one of the best film labs in the U.S.,” said James, worked to preserve the films, making sure to retain their original textures and material aspects. The entire process was further supervised by analog film specialists, who were on hand to tackle issues from degradation to color correction.

Gerard Malanga, The Filmmaker Records a Portion of His Life in the Month of August, 1968. Photo: © Gerard Malanga. Courtesy The Waverly Press.

Malanga’s films will be presented at the theater in conjunction with “Roger Jacoby: Pittsburgh Stories,” an exhibition and film program highlighting the late experimental filmmaker. Beginning in the 1970s, Jacoby’s work evidenced both inventive techniques and personal themes; he also ran in similar circles to Malanga, who introduced him to the Factory (Jacoby’s long-time partner was Warhol Superstar Ondine). Jacoby produced eight films before his untimely death at 41 in 1985.

James’s research has uncovered further and deeper ties between Jacoby and Malanga. For her, their connection bears out the Factory as a lively place of artistic production and experimentation as much as “social and creative exchange”—a moment that Malanga duly captured.

“They are a testament to Malanga’s role as a connector and collaborator,” she added of his films, “highlighting his influence on the artists who would define the era, while also showcasing the social dynamics that Warhol’s camera, often focused on the artist himself, might otherwise have missed.”

“Gerard Malanga: Secret Cinema” is on view at the Harris Theater, 803 Liberty Avenue, Pittsburgh, on December 14.