Museums & Institutions

German Museum Repatriates Ancient Marble Head to Greece

The Münster museum hoped to lend "moral support" to Greece in its mission to reclaim looted antiquities.

The Münster museum hoped to lend "moral support" to Greece in its mission to reclaim looted antiquities.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

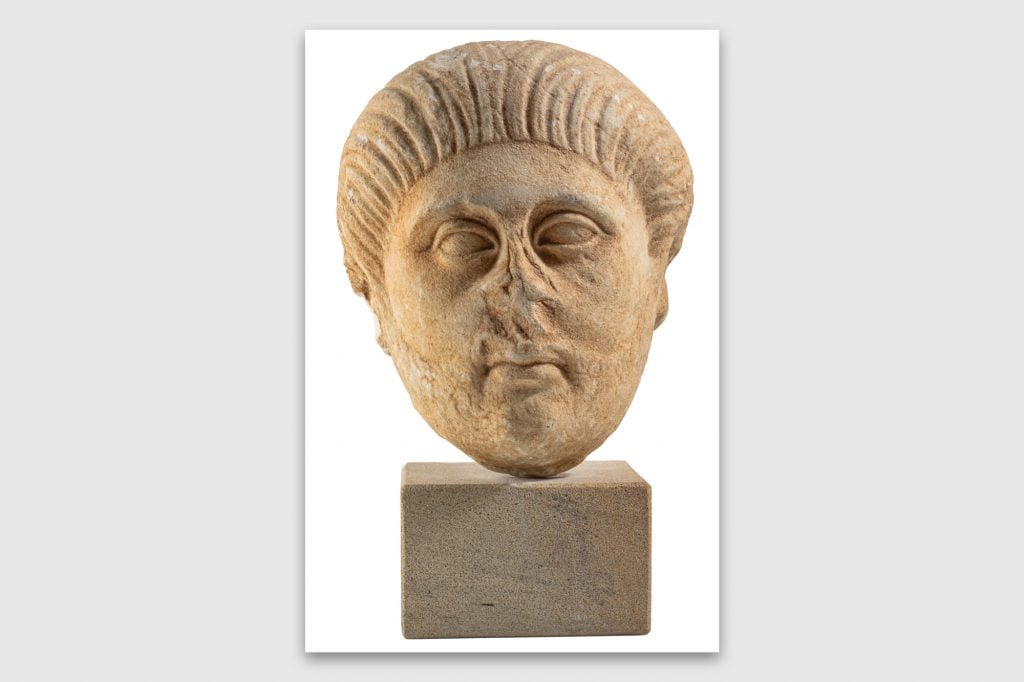

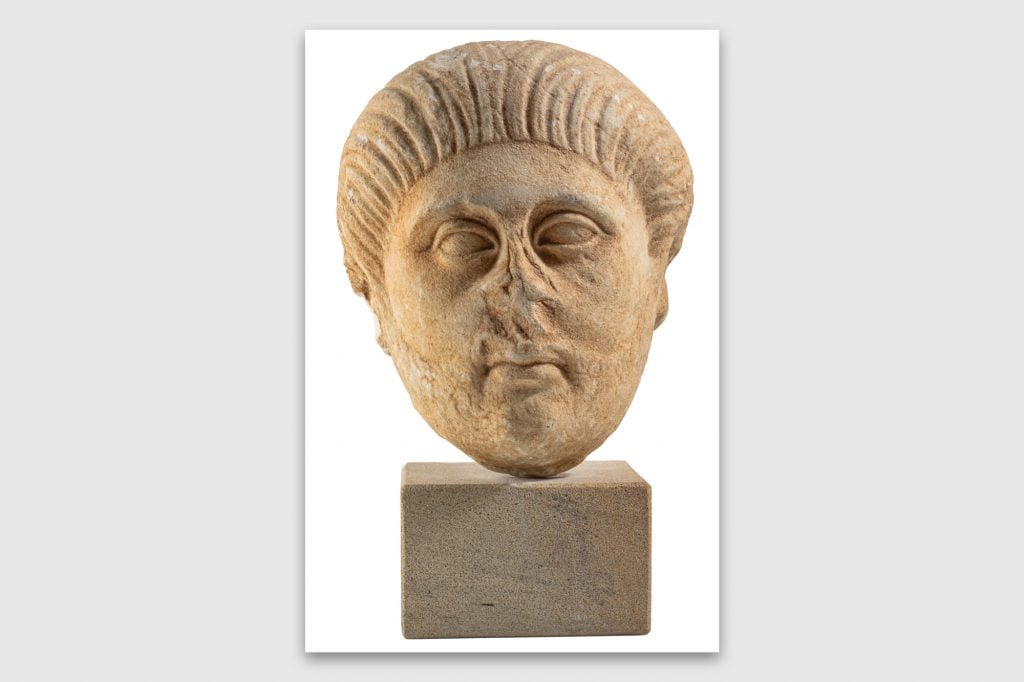

A German museum returned an ancient marble head to Greece during a ceremony on Tuesday, November 19. The object had been donated to the Archaeological Museum of the University of Münster in 1989, but it remains unclear how its previous owners came to possess it or why it was removed from its original location. It will now go on view at the Archaeological Museum in Thessaloniki.

The head was removed from a grave relief, it has been established by two German archaeologists Laura Stutenbecker and David De Vleeschouwer. They compared its style to that of grave reliefs in Thessaloniki, noting in particular hairstyle and the articulation of the facial features. By analyzing the composition of the marble and that of comparable heads in the Archaeological Museum in Thessaloniki, they found that it is from the same quarries on the island of Thasos in northeastern Greece. They dated it to 150 A.D.

“For me as the head of a university collection, it is a little painful that such an exciting object is leaving our collection,” admitted professor Achim Lichtenberger, the museum’s director, speaking at the ceremony. “But for me as an archaeologist, it is a happy day that this marble portrait is returning to its place of origin and can be viewed and examined again in its original historical context together with other pieces from the same workshops.”

Greek museum director Dr. Anastasia Gadolou and Prof. Achim Lichetnberger. Photo: © Archaeology Museum Münster,

Prior to entering the Münster museum’s collection, the head was privately owned in Essen, but nothing is known about how or when they acquired the head. This lack of proper documentation recording an object’s provenance was not unusual at the time of the donation but raises serious questions today.

“Unfortunately, we have to find again and again that some objects have come to the museum in ways that should not have been used according to ethical standards and the legal framework of the UNESCO Convention of 1970,” explained Litchenberger. “As an institution that is committed not only to research but also to the responsible training of future generations of archaeologists, we continually review our holdings.”

Lichtenberger said that the museum in Münster hoped “to provide moral support to countries like Greece that have been plundered in the past and are trying to return their antiquities.”

“The repatriation of antiquities that belong to Greece but are currently abroad, is a matter of national importance and high political priority,” the Greek culture minister Lina Mendoni affirmed at the ceremony, according to Greek Reporter. She applauded the museum for its voluntarily deciding to return the head, without Greece having to make an official repatriation claim.

Greece’s most high profile restitution claim relates to the Parthenon Marbles, which were removed from the Acropolis by Lord Elgin in 1816 and are now on display at the British Museum. In recent years, leaders at the London museum have been attempting to reach a compromise with Greece, most recently in the form of a “lending library,” proposed by new director Nicholas Cullinan. Any full restitution is currently prohibited by the 1963 British Museum Act, which outlaws public institutions from deaccessioning collection objects.