Art & Exhibitions

Alicia Keys and Swizz Beatz Triumph as Art World ‘Giants’

The musical powerhouse couple's collection tells the narrative of the Black experience with "Giants" at the Brooklyn Museum.

Kimberli Gant, curator at the Brooklyn Museum, has had a hectic week. On February 10, the museum opened “Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys,” the first exhibition to bring together art from the couple’s collection. It’s a landmark show not just for the institution, but for the power collecting couple, who have never seen so much of their collection in one place, at one time.

“Swizz came in last Monday night and we walked through it a little bit. He was so overwhelmed, he was texting his wife, ‘You’re gonna freak out,'” Gant told me. “Then, I saw the footage of [Keys] seeing the exhibition for the first time on the Today Show and she was bawling.”

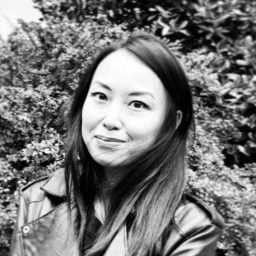

Kehinde Wiley, Femme piquée par un serpent (2008). The Dean Collection, courtesy of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. © Kehinde Wiley. Photo: Glenn Steigelman.

That emotion is not unsurprising. Over the 14 years they’ve been married, the singer-songwriter and her producer husband (real name: Kasseem Dean) have built an art collection close to their hearts, now numbering in the thousands. It’s so large that the couple’s three residences in New York, New Jersey, and California can barely contain it. For the first time, then, many of these works are emerging from storage.

The show’s opening over the past week may have left Gant slightly breathless, but she doesn’t miss a beat as she walks me through “Giants,” her enthusiasm apparent. About 100 works by 37 artists have been gathered here. The exhibition took two years to coalesce. A lot of that time, Gant explained, was wrapped up in conversations with the Deans, centered on rendering their collecting ethos into an exhibition narrative.

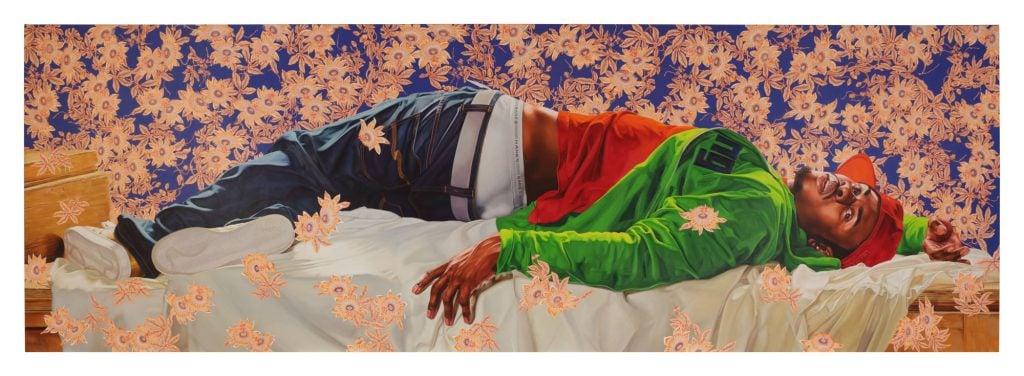

Ebony G. Patterson, . . . . they were just hanging out . . . you know . . . talking about . . . ( . . . when they grow up . . .) (2016). The Dean Collection, courtesy of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. © Ebony G. Patterson. Courtesy of the artist, Monique Meloche Gallery, and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Photo: Adam Reich.

“One of the main things for them is people of the culture owning their own role and culture,” she explained. “They said, look, we have a family, we want to see ourselves on these walls, and be able to create a legacy for our kids.”

Gant is referencing the historic erasure of Black culture and figures from the Western art canon—a lack of representation that the Deans are addressing by collecting the work of storied and living Black artists whom the couple deem “giants.” Fittingly, the show opens with Ebony G. Patterson’s room-filling installation, a glitter-lined ode to childhood. A pair of massive portraits of Keys and Swizz follow, resplendently painted by Kehinde Wiley, the artist’s Renaissance-esque flourishes an act of reclamation.

Esther Mahlangu, Ndebele Abstract (2017). The Dean Collection, courtesy of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. © Esther Mahlangu. Photo: Glenn Steigelman.

The adjacent gallery kickstarts the motif of “Giants” with a showcase of works by Black artists whose legacies paved the way for today. Basquiat is here, as is Barnes. But the spotlight belongs to a trio of canvases by Esther Mahlangu, bearing the striking geometric language of the South African artist’s Ndebele heritage. The Deans, said Gant, “really want to emphasize the idea that artists should create beyond what they think their limits are,” highlighting how Mahlangu translated her background in house-painting into a fine art career. “This is a legacy that has been happening for generations upon generations that most people don’t know about,” she added. “Now, it has a worldwide following, but it starts on the shoulders of giants.”

Installation view of “Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys” at the Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Danny Perez.

It’s on those shoulders that the artists in the following room stand on. Here, the space is dominated by a sequence of large-scale paintings by Meleko Mokgosi. Titled “Bread, Butter, and Power” (2018), the vivid series sees the artist pointedly critiquing the asymmetrical power structures in his native Botswana. A painting of a lone man in a drab room illustrates the reality of domestic work, Gant pointed out; another of a group of Black children dressed in typically British school uniforms alludes to the unequal access to education.

These are quotidian scenes, but, Gant stressed, “It’s layer upon layer upon layer of history. It’s an epic of the mundane.”

The unseen systems at work against Black communities also surface in neighboring works. Henry Taylor‘s stark portrait of a homeless man, Jordan Casteel‘s compelling depiction of a Black vendor, and Hank Willis Thomas‘s powerful sculpture Strike (2018) “create a sense of visibility,” Gant said, around the lived experiences of Black folk.

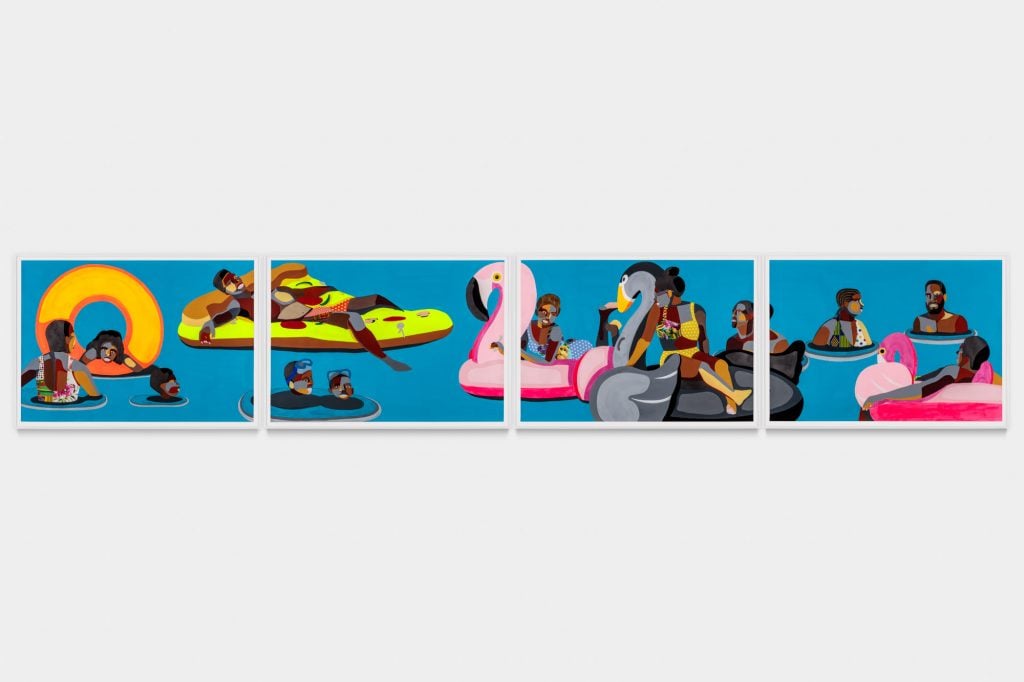

Derrick Adams, Floater 74 (2018). The Dean Collection, courtesy of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. © 2023 Derrick Adams Studio. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures.com.

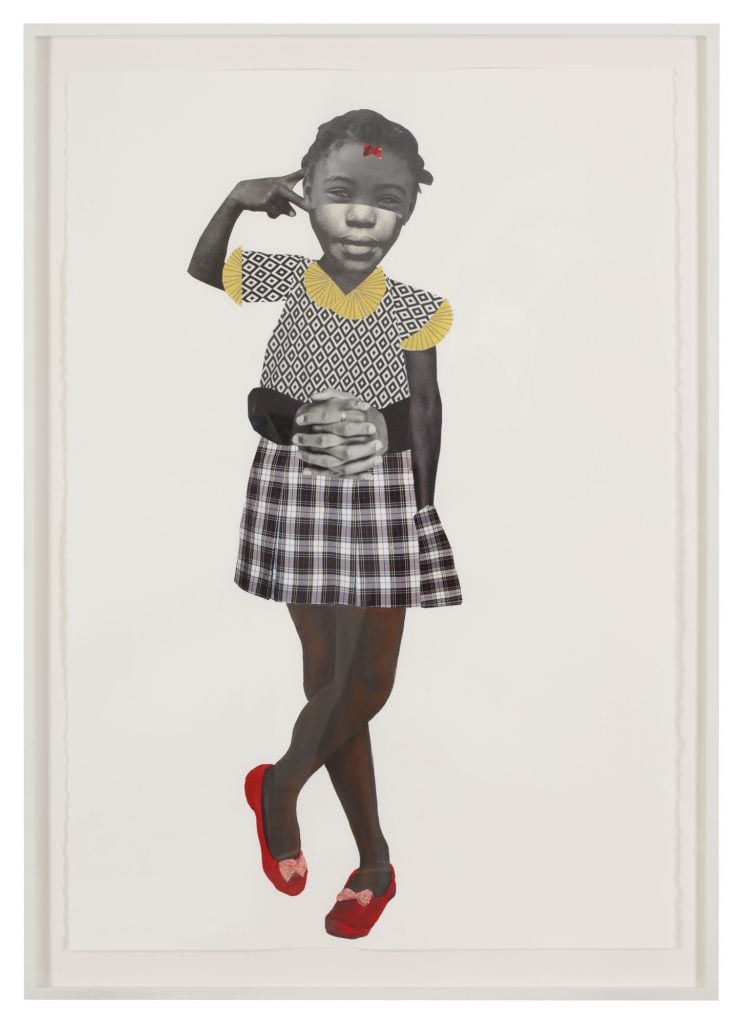

And Black people have fun, too. Derrick Adams‘s Floater 74 (2018), depicting a luxurious pool scene complete with giant floats and sunbathers, leads into the following section celebrating Black excellence. Gathered here are works by contemporary artists, including Frida Orupabo, Deborah Roberts, Tschabalala Self, and Mickalene Thomas, whose playful and thoughtful experiments with medium and material are currently enriching the Black visual vernacular.

It’s also here that the Deans’s forward-looking approach to collecting is borne out. As collectors, their aim is to build for posterity, not simply showcase. As Swizz explained in a video accompanying the exhibition, they are not in the “hype race of collecting.” He added: “It’s for the longevity play.”

Deborah Roberts, The Visionary (2018). The Dean Collection, courtesy of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. © Deborah Roberts. Photo: Glenn Steigelman.

Which is not to say the Deans don’t get to live with their art. Gant pointed out that she first encountered Keys and Swizz’s art collection in the pages of Architectural Digest, in a 2021 feature highlighting the couple’s oceanfront home and art trove. That domestic scene is recreated in “Giants,” in two separate alcoves where visitors can recline on plush armchairs to take in a group of delicate landscapes by Barkley L. Hendricks in one and a serene series of ballerina portraits by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in another.

What can’t go unseen is a section dedicated to photography. Jamel Shabazz‘s joyous street-style images from the 1980s are arrayed on one wall opposite one of Gordon Parks‘s genre-spanning photography. The Deans own the largest collection of Parks’s works in private hands and “Giants” does justice to his oeuvre, displaying his visual records of the U.S. civil rights movement as much as his commercial photography.

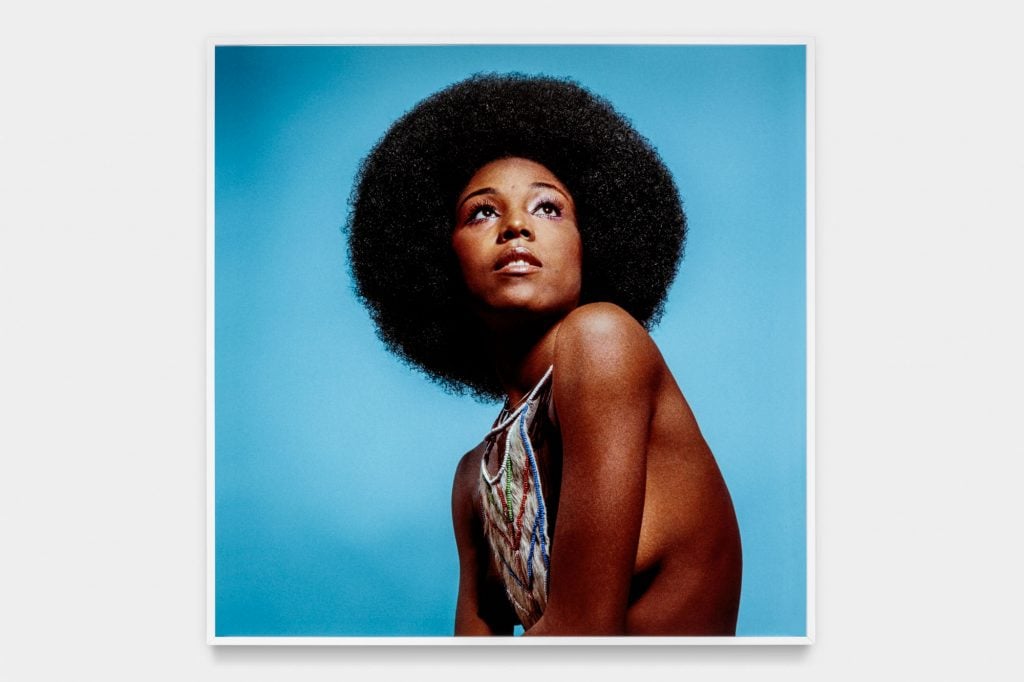

Kwame Brathwaite, Untitled (Model Who Embraced Natural Hairstyles at AJASS Photoshoot) (c. 1970, printed 2018). The Dean Collection, courtesy of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. © Kwame Brathwaite. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures.com.

The exhibition’s theme is, quite literally, amplified in its closing gallery, which brings forth gigantic works from the Deans’s holdings. There’s a vast canvas by Titus Kaphar, his signature splice evident; a buoyant spread by Nina Chanel Abney; and Amy Sherald‘s twinned tributes to the dirt-bikers.

But to see all of it, you’ll have to navigate Arthur Jafa‘s towering Big Wheel I (2018), an eight-foot-tall monument, crafted with a tire and chains, that confronts the trauma of racial violence via the monster truck culture of his native Mississippi. It’s a formidable, breathtaking sculpture. “This work isn’t fitting in the house,” Gant said with some understatement.

Installation view of “Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys” at the Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Paula Abreu Pita.

More vitally, the work takes up space—institutional space that’s historically been reserved for white representation, but also the spaces within the cultural canon and consciousness—as it should. Which, ultimately, underscores the Deans’ efforts in giving air to Black joy, pain, resistance, and resilience, urging Black creators, they said, to “be our most giant selves.” That, as the exhibition demonstrates, would dwarf the biggest room.

“All this work,” noted Gant, “has a presence.”

“Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, New York, through July 7.