Art World

Plans to Raze Gio Ponti Villa in Iran Spark Protests by Architects and Experts

Iconic Villa Namazee set to be demolished and replaced by a luxury hotel.

Iconic Villa Namazee set to be demolished and replaced by a luxury hotel.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

A villa by the Italian architect Gio Ponti in northern Tehran is to be demolished and turned into a five-star hotel, sparking outrage among architects and cultural heritage experts in the country.

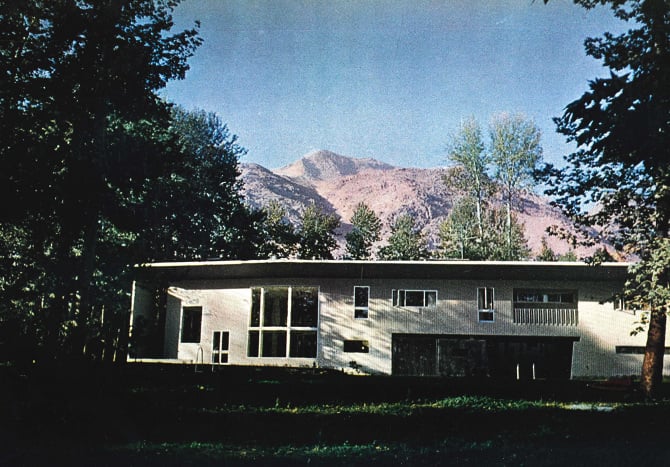

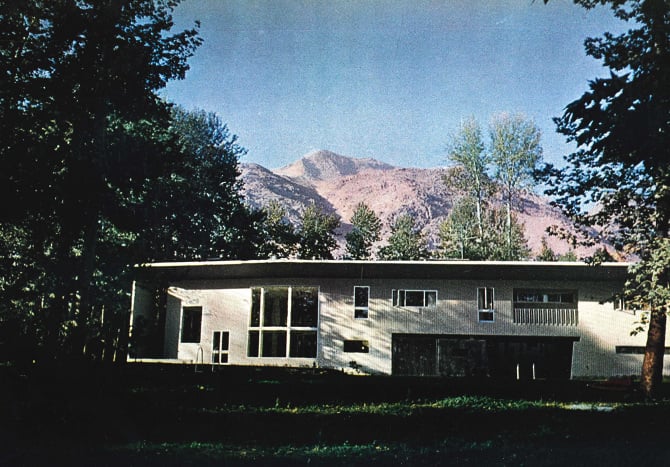

Villa Namazee, commissioned by the by the businessman Shafi Namazee, was built in the early 1960s in the city’s wealthy district of Niavaran. It is the last intact building by Ponti that remains in the Middle East.

The house is one of the three famous villas built by Ponti (the other two are in Venezuela). The Milan-born architect and designer, who came to symbolize the best in Italian modern architecture, was also the founder editor of the prestigious Domus magazine.

After the 1979 Islamic revolution, Villa Namazee was possessed by the government and used as a local registry office, the Guardian reports. It was subsequently sold to Ahmad Abrishami, a representative of Nokia in Iran, who registered it as a national heritage building.

The villa was sold to its present owner four years ago, though, and a court decision has now allowed him to overturn its national heritage status, so plans for the construction of the 20-storey hotel can begin.

“The building has been legally taken off the list, so the only way to save it is for the municipality to bring it under public ownership or exchange it for other properties,” Mohammad-Hassan Talebian, deputy head of Iran’s cultural heritage, handcrafts, and tourism organisation, told the Ilna news agency.

An anonymous collective, which goes under the name of “the people’s committee to protect Tehran’s public houses,” has disseminated an online leaflet to save the building from demolition, explaining its historical, cultural, and environmental relevance.

Leila Araghian, the architect who designed the Tabiat Bridge in Tehran—which won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture this year—attempted to visit the villa along with Ponti’s son.

“We went there and buzzed the door, a caretaker came out and said the owner wasn’t there, so we went to the house opposite and took pictures from there. This is a building designed by such an important architect. If it was anywhere else, it would have been protected,” she said.

The architect Gio Ponti in the 1950s. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Still, Araghian said that the campaign to save the villa was a sign of improving sensibilities in the country. “The fact that the Iranian society and Iranian architects are sensitive about this is positive by itself, it shows they are not indifferent. If it was 15 years ago, it would have been destroyed without much resistance,” she said.

Fellow Iranian architect Faryar Javaherian also voiced her outrage. “It is a master’s house. It is one of the first projects of its kind featuring open plan with a suspended roof which also has a flooring that appears to be floating in the air. The ceramic used [by artist Fausto Melotti] is very, very beautiful.”

“If they want to build a hotel, they still can preserve the villa, it’s an added value, it’s not a distraction. You have something good, why destroy it and replace it by something so awful?,” she lamented.

Meanwhile, Nashid Nabian, a young Iranian architect and Harvard graduate, complained about the lack of respect in the country towards modern and contemporary culture.

“To go beyond our identity crisis, we always look back to our old history but our contemporary history is as significant,” she told the Guardian.