Art History

The 19th-Century Painting That Made Ridley Scott Give the Thumbs Up to ‘Gladiator’

"Whatever the script is, we’ll get it right. I’m doing this movie."

"Whatever the script is, we’ll get it right. I’m doing this movie."

Tim Brinkhof

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.

You’d think that Ridley Scott’s iconic 2000 film Gladiator, about a Roman general who ends up fighting for his life inside Rome’s Colosseum after emperor Marcus Aurelius is succeeded by his volatile son Commodus, was based on a Roman history book like Anthony Birley’s 1976 bestseller Lives of the Later Caesars or Aurelius’s own Meditations (161–180 C.E.), a cornerstone of Stoic philosophy.

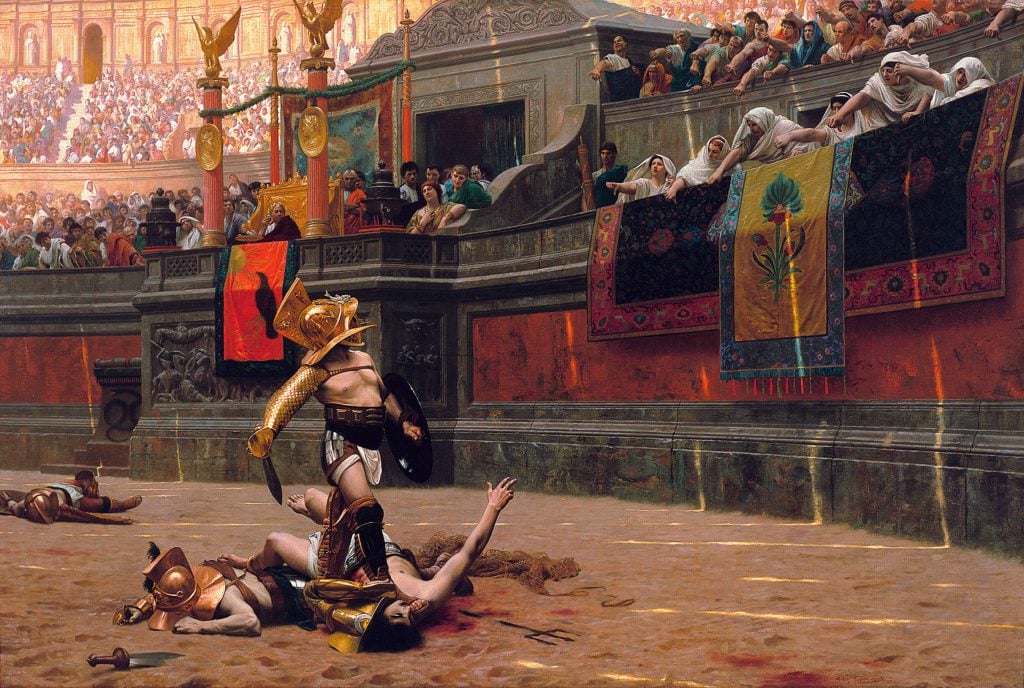

In truth, the film—whose long-awaited sequel, Gladiator II, is currently playing in cinemas—was inspired by a painting from 19th-century France. Pollice Verso, by the academic giant Jean-Léon Gérôme, is a dramatic rendition of a gladiator who, having bested his opponent, turns to the audience and the emperor for their judgement of his defeated foe.

“It was beautifully shaded, and because it was sort of in the blush of the British empire, it was slightly idealized,” Douglas Wick, a producer of the Gladiator franchise, recounted in a recent interview with the Hollywood Reporter. Wick and his colleagues had been trying to get Scott on board for a while, and Gérôme finally helped them close the deal: “Ridley looked at the painting and said, ‘I’ll do the movie. Whatever the script is, we’ll get it right. I’m doing this movie.’”

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Pollice Verso (1872). Collection of the Phoenix Art Museum.

“Walter and Doug came by my office and laid a reproduction of the painting on my desk,” Scott himself said of the meeting in an interview for the book Gladiator: The Making of the Ridley Scott Epic, published shortly after the film’s 2000 release. “That image spoke to me of the Roman Empire in all its glory and wickedness. I knew right then and there I was hooked.”

He was hardly the first filmmaker to take inspiration from Gérôme, whom the art historian Marc Gotlieb once applauded for his ability to forge “narrative practices that would take cinema decades to invent.” Long before Gladiator went into production, Gotlieb said, performance artists like the Ringling Brothers made a name for themselves staging his paintings for live audiences.

Pollice Verso, Latin for “with a turned thumb,” refers to the iconic gesture by which the Colosseum’s visitors let the gladiators know whether they deserved to live or die after each fight—a call commonly reserved for the emperors, if they were present. In Gladiator, the painting’s scene is reimagined when Commodus, played by Joaquin Phoenix, judges the merits of Russell Crowe’s Maximus.

Everyone who knows a thing or two about the Roman Empire knows this is how gladiatorial games worked. However, that’s mostly because of the success of Gérôme’s painting. Ask any professional historian, and you’ll get a wide variety of opinions as to what this gesture, which ancient documents mention but never properly explain, actually looked like.

While some believe, as Gérôme probably did, that thumbs up meant mercy and thumbs down death, others insist that the pollice verso gesture involved turning the thumb horizontally, or hiding it inside the hand, behind the other fingers.

A view of the Colosseum in Rome, Italy. Photo: Osmancan Gurdogan/Anadolu via Getty Images.

While the historical accuracy of Gérôme’s Pollice Verso and by extension Scott’s original Gladiator are left ambiguous, its 2024 sequel wholeheartedly breaks with the past to provide a version of the Roman Empire that’s more magical than it is realistic.

For example, while exotic animals like rhinoceri were certainly kept inside the Colosseum, ancient documents indicate they only fought against other animals, not humans. (Needless to say, no gladiators rode them into battle, as they do in the film.)

Likewise, while we know that the Romans sometimes flooded arenas to reenact naval battles—a major plot point in Gladiator II—there is some historical debate about where these water shows took place, with many historians insisting they were held at the Circus Maximus due to it being more easily flooded than the Colosseum. (And that’s to say nothing of the presence of sea life in the Gladiator II naval battle that led so many detractors to say the movie had jumped the shark—literally.)

Regardless of its historical accuracy, Pollice Verso remains among the most spellbinding visualizations of gladiatorial games ever produced.