Art World

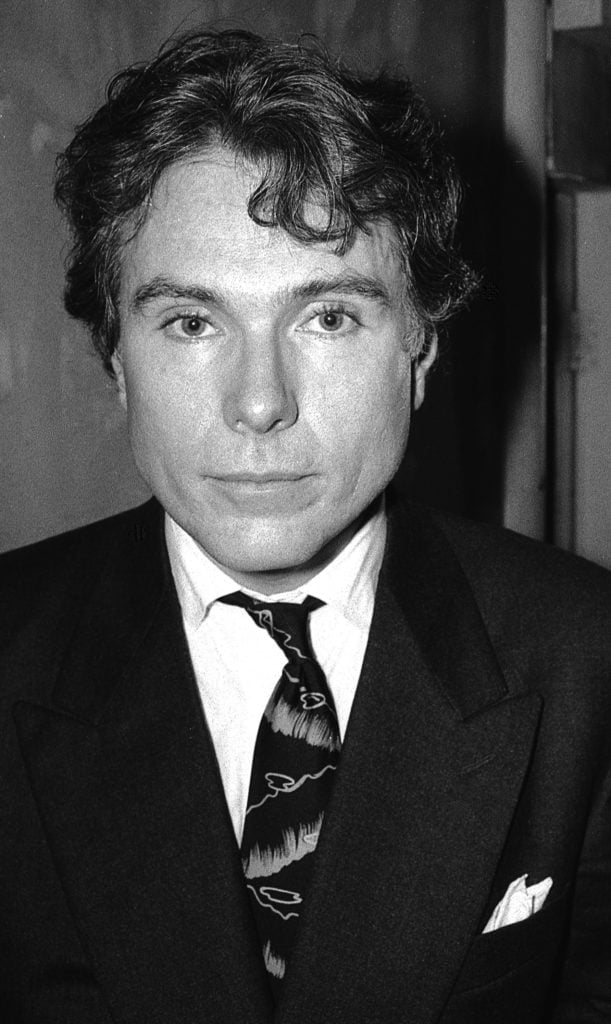

Glenn O’Brien, Legendary Arbiter of New York City’s Art and Fashion Worlds, Has Died at 70

He left his witty, elegantly cosmopolitan mark on nearly every aspect of the city's culture.

He left his witty, elegantly cosmopolitan mark on nearly every aspect of the city's culture.

Andrew Goldstein

Glenn O’Brien, the art scribe, power editor, downtown personality, fashion guru, and all-around arbiter elegantiae who either chronicled or inspired what was cool in New York City over the past four decades, has died at the age of 70. His passing was confirmed by his wife, the publicist Gina Nanni, who said that he had passed away in New York after a sudden onset of pneumonia exacerbated a longtime illness.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, O’Brien gained a taste for journalism at Georgetown University as the editor of the Georgetown Journal—a little campus paper whose founding by the legendary publisher Condé Montrose Nast foreshadowed O’Brien’s glossy destiny. Coming to New York afterwards and studying film at Columbia University, he fell in with the bustling scene around one of that city’s most famous film-dabblers, Andy Warhol, and in 1971 found himself named the first editor of the Pop artist’s in-house magazine, named Interview after Warhol’s favored style of celebrity coverage.

Glenn O’Brien at Basquiat’s memorial in 1988. Photo by Todd Eberle

This was the beginning of one of the most storied editorial runs the New York media world has seen. After a three-year tenure at Interview, O’Brien took over Rolling Stone’s New York bureau, then became editor-in-chief of High Times; helped found Bomb and Spin magazines; served stints at Allure and Harpers’s Bazaar; wrote a column for Artforum and another one, the famed “Style Guy,” for Details and then GQ; edited Madonna’s infamous Sex book; became the editorial director and CEO of Brant Publications—which by then owned Interview as well as Art in America—for a short year; led Bergdorf Goodman magazine in 2014; and was tapped as editor-at-large of the lad mag Maxim in 2015. (That masthead title, “editor-at-large,” is reputedly an O’Brien invention; he came up with it as a joke at High Times, riffing on both the fact that he preferred to steer clear of the office and the way he wished to be categorized by the law-enforcement community: “at large,” i.e. un-arrested.)

This curriculum vitae, enough to populate the resumés of several mere mortals, was perversely only a part of O’Brien’s story. For instance, there was his televisual career: in 1978, he and Blondie guitarist Chris Stein stormed the public-access airwaves with “TV Party,” an arch but access-blessed talk show featuring the luminaries of New York’s creative underground, from Basquiat to the Talking Heads’s David Bryne. (The show ran for five years, and was re-released in DVD form in 2005.) Basquiat would also become the subject of the documentary Downtown 81, which O’Brien wrote for the director Edo Bertoglio in 1981.

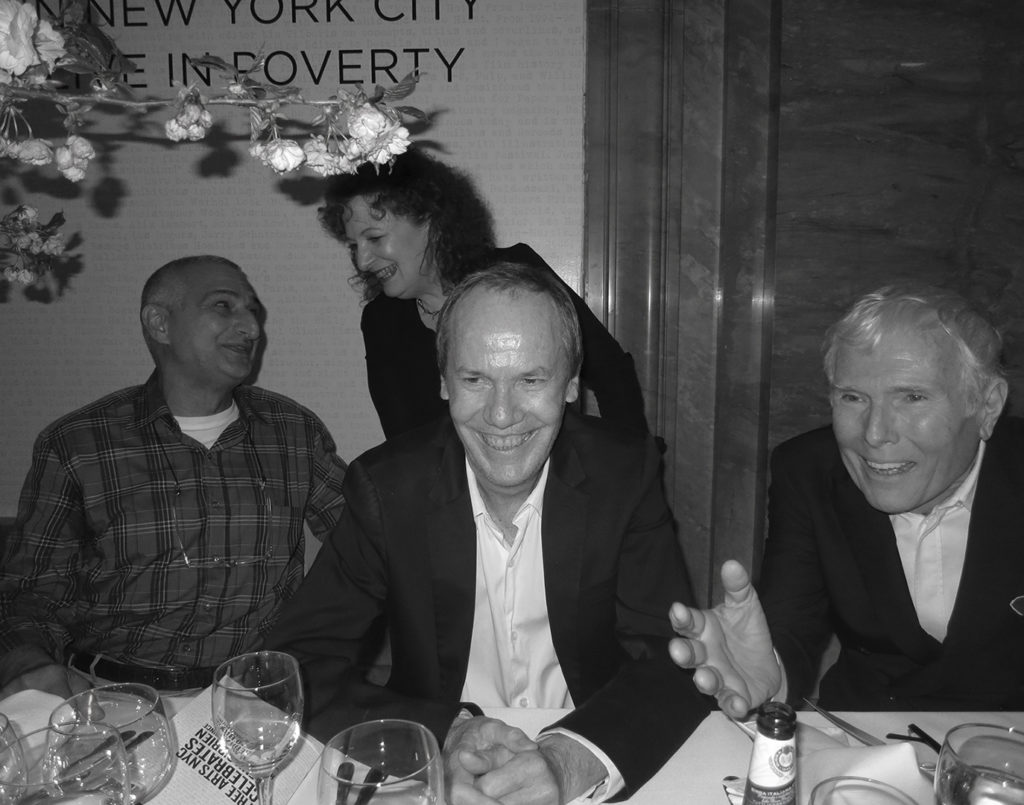

Glenn O’Brien at a reunion of Warhol’s Factory. Photo by Todd Eberle

Then, there was the fashion career, the true depths of which were little known in his lifetime. In addition to writing his “Style Guy” column for 16 years, dispensing advice on everything from what to pair with loafers to how to treat starlets, O’Brien worked behind the scenes at the highest levels of the fashion industry to help brands craft their messaging—it was how he paid the bills for his enviably comfortable lifestyle. For many years he was the creative director of Calvin Klein, helping to produce a wealth of the company’s most memorable advertising campaigns (CK Once, CK Be, Eternity, and Escape, among them), using his Warholian panache for improvisation to write lines of commercial poetry on-set that then came out of the mouths of Kate Moss and Milla Jovovich in widely watched commercials.

O’Brien, an effortless celebrity wrangler with his own undeniable star wattage, also worked with Dolce & Gabbana, Charlize Theron and Johnny Depp for Dior, and Brad Pitt for Chanel No. 5. “He had an incredible gift and he could write for advertising in a way that was just magic,” says Nanni, whom he in fact met while working as the creative director of Barney’s.

As dapper as you might expect in-person, O’Brien wore his expertly chosen clothes lightly, mixing and matching high with low but never vulgarly—an apt metaphor for his approach to much else in his life, where he seemed to treat his various roles as marvelous larks. Having him show up in a publication was a bit like Bill Murray popping into your neighborhood softball game, in that it would make a splash, leave an unforgettable impression, and not last long.

Glenn O’Brien with (from left) Christopher Wool, Nan Goldin, and Richard Prince. Photo by Todd Eberle

Knife-thin in his youth, like the punk rockers he chronicled for a regular Interview column in the ‘80s, he matured over the years to resemble a roman statesman with his stately corona of close-trimmed grey hair and matching beard. He was an unmistakable éminence grise, in other words, at the many art events he showed up at, often to support friends like Richard Prince (a close confederate and co-conspirator), Christopher Wool, Nan Goldin, Tom Sachs, and James Nares.

Quick to pick up the latest technologies to—again, like Warhol—capture and broadcast his starry milieu of creatives, O’Brien in recent years had been an avid Instragrammer under the handle @lordrochester (in honor of the British peer called “the cynosure of the libertine wits of Restoration England” by the Poetry Foundation) and also hosted the short-lived interview program “Tea at the Beatrice” on Apple TV.

At the time of his death, O’Brien was in the middle of a customary welter of book projects, and working on a new TV show. He was, to the end, a very busy man.