Futura (né Leonard McGurr, FKA Futura 2000) was one of ’70s New York’s graffiti all-stars who crossed over into the early ’80s art boom. Whether painting on a subway car or canvas, Futura’s masterful, otherworldly abstraction set him apart from his brethren. But after initial dalliances with top galleries and high-profile gigs like live painting backdrops for the Clash on tour, he stepped away from it all just as peers like Basquiat and Haring were going stratospheric.

In short order, he hustled as a bike messenger, worked at a Queens post office, and became a streetwear impresario, graphic designer, album-art aficionado, high-fashion collaborator (Louis Vuitton, Comme des Garçons, Off-White), and brand unto himself (Futura Laboratories is the umbrella for his commercial offshoots). Through it all, he worked just outside of the art world as his legend grew. Now 66 and no ingénue, Futura has been making a concerted turn back toward the art world.

First there was “Futura 2020,” a show of new paintings at Eric Firestone Gallery, which marked his representation with the gallery. Now, Futura has a solo exhibition at the dealer’s East Hampton outpost. “Tarpestries” (a portmanteau of tarp and tapestries) presents a series of large-scale, suspended spray-painted works.

Is this preamble for something bigger? “There’s nothing announced right now, but there is some American institutional play happening next year,” Firestone said.

Last week, we caught up with Futura as he prepared new work for Singapore’s Art SG fair in January in Firestone’s fourth-floor studio space down the street from the gallery. The artist—thin and beatific—sat cross-legged on the floor, spliff in hand.

Futura prepares his Tarpestries. Photo by Shilei Wang.

I was quite taken with you in the recent The Andy Warhol Diaries documentary. You were very reflective and not self-aggrandizing. It showed real evolution and honesty to say that latent homophobia might have held you back.

Thank you. A lot of people have said, “Hey, you know, you were really good in that.” It’s hard to explain to people the time in which I grew up—not just the way I was raised, but the fear I had. I’m gonna be 67. I’ve evolved so much as far as what I believe. I was fresh out of a four-year military experience, where I had this thing about my testosterone and what a male is supposed to be. Once AIDS happened, I fell into the fear of that too, and then people started dying. I was afraid that through association, there would be implication… I always felt my work was different. I was really into my identity, very conscious of what I looked like.

Were your parents ever aware of your success?

No. They never saw me as a success. I hadn’t done anything. I was Futura before I went into the Navy. I started to write graffiti at the age of 15 in 1970. I left home at 18 to join the military. My mom was encouraged: “Maybe you’ll get to see something in the world, learn to do something.” She passed in ’75. When I came outta the military in ’78, I came back to New York and I reconnected with my friends. The movement on trains had not only accelerated, but was blossoming. And so, I got back into that thing.

My dad passed in ’85, the beginning of what I saw as the end of the first period of my career. We speak of the ’80s as remarkable, but it’s really the first half of that decade that’s amazing. The last half is not that great. For me, it was over as far as the contemporary artist Futura, because I couldn’t sustain it. We had too many other people rising up. Street artists were elevated now, obviously Basquiat was, Keith [Haring] was, even Kenny [Scharf] was. We were all at [Tony] Shafrazi [Gallery] at one point, and I was batting eighth on a starting lineup. I had a two-year-old son, and I just couldn’t make it as a gallery artist. It just wasn’t working and people weren’t really interested anymore in graffiti per se. So, it was my exit. I became a bike messenger.

But what was holding you back?

I don’t think it was the work. It was the gallery system, the “art world,” and who the rising stars were. Jean-Michel [Basquiat] dominated that decade. Very few people were allowed in those rooms. The fact that I even got a small taste of it was interesting for me. People were comparing me in 1984 to [abstraction pioneer Wassily] Kandinsky. I didn’t know anything about these artists. The way they were referencing art history to try to tell these stories—how do you compare me to an artist I’ve never heard of? Why are you comparing me to [Rococo painter Jean-Antoine] Watteau?

It sounds like you had a touch of the “angry young man.”

I was angry. I was working very hard and, ironically, paintings of mine from the early ’80s go for pretty good money on the market, so it’s a testament to what I felt. I look back at old work and I’m like, damn, how’d I do that?

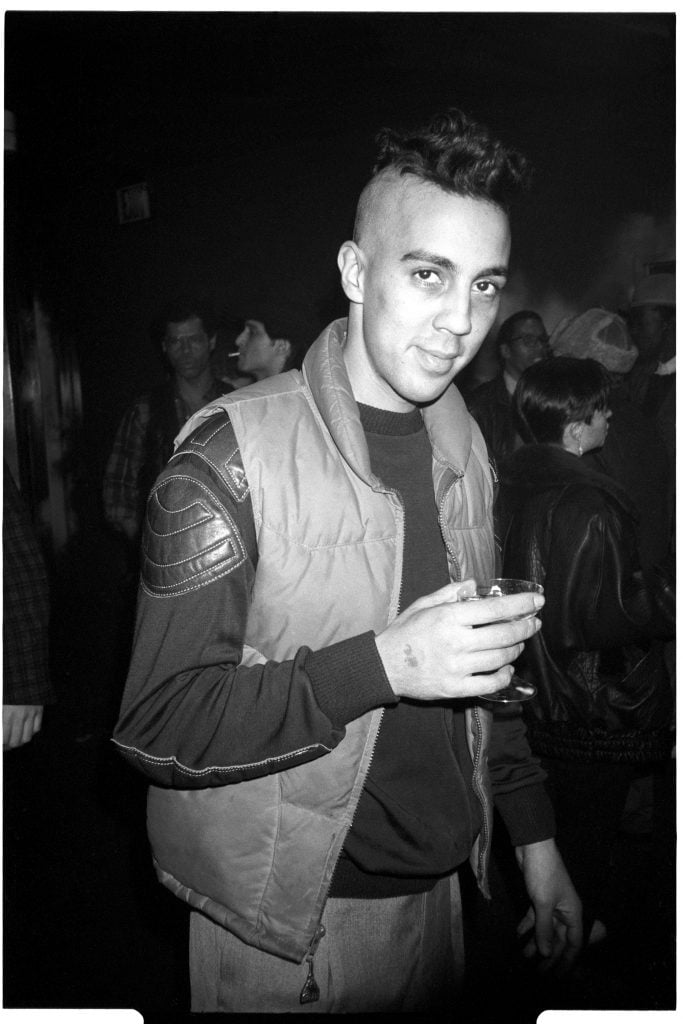

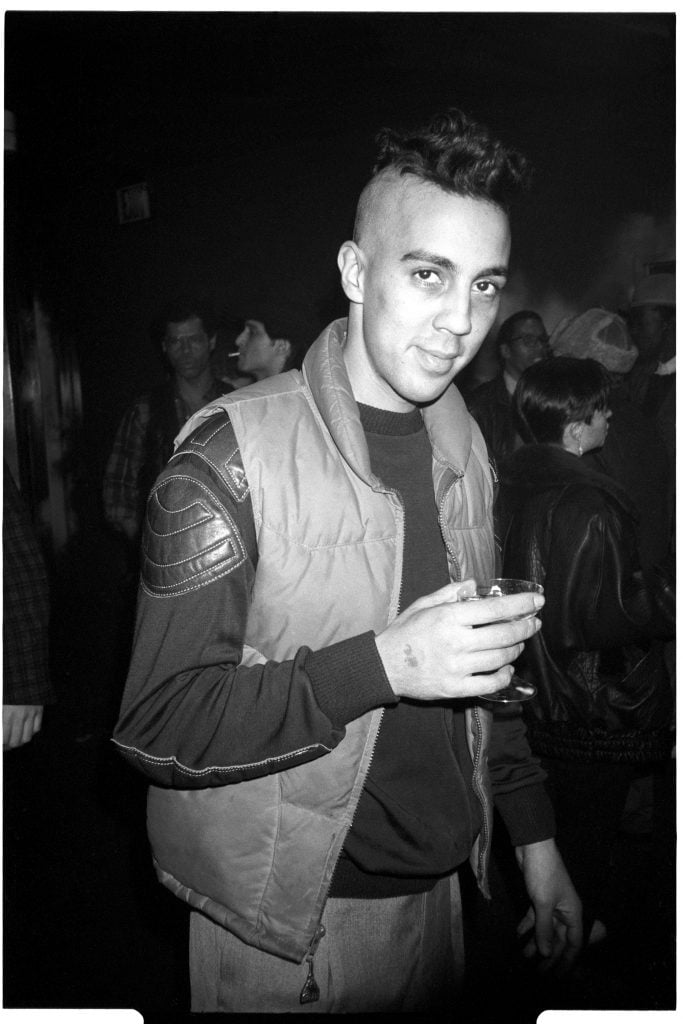

Futura 2000 in 1986. (Photo by Patrick McMullan/Getty Images)

This leads us to your wandering in the desert as a bike messenger period. How do you view this?

Survival. The Europeans opened their arms and wallets to purchasing graffiti art in that period. Crash, Daze, Lady Pink—they just kept doing it. I didn’t love it that much because, once again, I’m looking at my kid and I’m like, “This isn’t gonna work.” So I just started hustling. Being a messenger was so free. I worked for two companies. Sprint—not the phone company—and Elite Couriers, which was the New York Yankees of messengering. You could make $100 a day.

A New York bike messenger was such a stylish job, too.

We were super cool. I used to ride a fixed bike with no brakes. It was a danger game that I was thrilled by until ultimately I got hit and taken off the road and I had a huge cast on my leg. Right after that, I made a decision. This isn’t safe; it’s a kind of a weird, sketchy job. Then the fax machine came and everybody got scared.

Finally, I had an exhibition in ’88. A gallerist, Philippe Briet, who has since passed away, came to me and was like, “What happened to you?” He had a storefront gallery and one of those basement entrances where you open the gates and you can go down the stairway. In Soho, there’s a lot of these and they used to rent them out to kids to sleep in. They were also artist studios with no ventilation other than the entrance and exit. I got a show with Philippe and then he introduced me to Agnès B., the clothier and global humanitarian extraordinaire. She came to my rescue.

How was it to start painting again?

I was happy. Agnès set me up for a period of two years. All she wanted out of it was at the end of each year, two paintings. I’d never met anyone that benevolent. It was weird. It felt like a scam. But no, it was just a wonderful person investing in something she liked. Finally, I was able to get my ideas organized. For my comeback in the late ’80s, I think the work was good. I’d been pent up for a few years. I kept that Williamsburg studio for 20 years; I only lost it in like 2008.

If they hadn’t come out of the woodwork to help you, do you think you would have resumed being an artist?

I don’t look at my life that way. Everyone has a very important role and purpose.

But after Agnès’s intervention, you weren’t automatically a hugely successful artist.

No, I was still pretty much under the radar. This leads into the ’90s, when I was still conflicted. That moment in my life was a series of popup shows rather than anything substantial with real representation. And then Philippe died. He was gone by ’92. Now you have the arrival of—I hate the term—street art. By the early ’90s, here comes streetwear.

The ’80s spit out all these ex-graffiti, creative people. But that art-world thing wasn’t really viable [for them]—people were getting into other ways of creative expression through graphics. I very much got involved in that. I was trying to do graphics digitally, and we started clothing companies. My attention went very much away from the art world. I wasn’t ready for it or it, me. By now, the graffiti movement, the rap, hip-hop culture really started to explode. The European movement has already begun. This whole thing is starting to bubble globally.

Futura’s bronze sculpture 39 Meg. Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery.

I became aware of you from those the album art you did for the first Mo’Wax and UNKLE records. The music and imagery really encapsulated that era of pre-millennial tension, mysterious scratchy foreboding instrumental hip-hop paired with aliens and abstraction. Was that the birth of your man/mutant/alien “Point Man” motif?

I met James [Lavelle, Mo’Wax founder and member of UNKLE] in ‘92 in Berlin at a bike messenger championship. I brought James to that studio on Hope Street. Those were the initial Point Man images. Even the one he used as the logo, the kind of two characters in a triangle. That was an actual painting that I had. I made some really interesting character pieces at Hope Street during the early ’90s— the one that James got, it just became popular. We made an action figure of [Point Man] in ’97 and that’s when he kind of got his identity.

Why did this character speak to people? Why did he become your Hello Kitty?

Keith Haring had that entire character universe that he could do so effortlessly. But he would always come back to a couple of very basic ones—the crawling baby and the barking dog. He said to me, “You really need to have an iconic identifier.” When I did the Point Man, I was inspired by H.R. Giger’s Alien. I was more into painting abstract things, but James really gravitated to them.

Futura’s The Metallic Age. Courtesy of the artist and Eric Firestone Gallery

In the new show, you have these massively scaled tarps hanging from grommets. I love a grommet. What stands out for you?

There’s a huge character piece that [Supreme founder] James Jebbia actually purchased. It’s the first time I’ve done a bronze sculpture. The exhibition’s being shown in two separate locations, a couple hundred meters apart. There’s the traditional gallery space, and the statue, 39 Meg, is in the window down the block. As a three-dimensional object, he’s crazy. When I look at my work, I am very critical. I think the largest painting, The Metallic Age, is really one of my stronger ones. It’s playing with positive and negative space. I see a fluidity to it.

Installation view of FUTURA: TARPESTRIES at Eric Firestone Gallery in East Hampton. Image courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery.

Why is spray paint still the most important tool for you as an artist?

It’s the major shareholder in the work. I think it’s the experience I have with it. I always see it as the foundation. I may add to it, but usually it doesn’t need anything else.

“Futura: Tarpestries” is on view at Eric Firestone Gallery, 4 + 62 Newtown Lane, East Hampton, New York, August 6–September 18, 2022.