“Do you occasionally take pleasure in what you have?” begins a letter to Cornelius Gurlitt from his sister Renate, describing a trove of some 1,500 artworks that their father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, a Nazi-era art dealer, has left behind. “It sometimes seems to me that his most personal and valuable bequest has become the darkest burden on us.” The tainted inheritance she refers to had been largely amassed by their father after he had been enlisted by the Nazis to sell so-called “degenerate” art purged from German museums, and, later on, in his capacity as the buyer for Hitler’s unrealized mega-museum project, the Führermuseum in Linz.

The trove was discovered in 2012 in Cornelius Gurlitt’s Munich apartment after he had attracted the attention of the German tax authorities when he was caught traveling to Switzerland with a suitcase filled with cash and works on paper. But the public didn’t learn about the sensational find until the German magazine Focus broke the story in 2013, raising uneasy questions about the secrecy, the artworks’ value, and, of course, their provenance.

This week, after years of accusations against the German government’s lack of transparency in the handling of the trove, over 400 works from the Gurlitt collection went on view in two institutions in two different countries: The Kunstmuseum Bern, in Switzerland, which Cornelius named inheritor of the collection when he passed away in 2014, and the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, Germany. Both shows will travel to the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin next September.

What the Kunstmuseum Bern Actually Gets to Keep

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Two Nudes on a Bed (Two Models), (around 1907-8) ©Kunstmuseum Bern

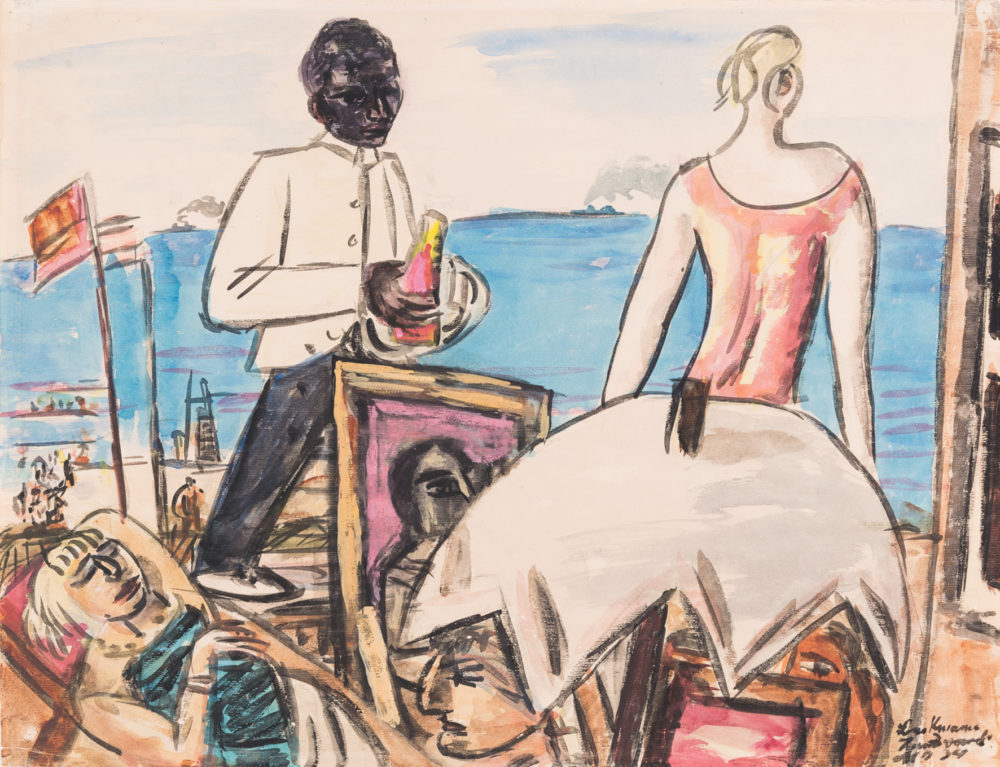

The Bern museum, which was shocked when it learned about Gurlitt’s bequest, has only accepted into its collection works whose provenance has been cleared, which make up roughly a third of the 150 pieces in the show. Focusing on so-called “degenerate” art that the Nazis seized from German museums, the exhibition includes stunning works of German Expressionism, Berlin Secession, and the Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter movements, with works on paper—the medium that makes up the bulk of the Gurlitt collection—by artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, August Macke, Otto Dix, Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, Käthe Kollwitz, Paul Klee, and Emil Nolde (although a member of the Nazi party, his style was still deemed “degenerate”).

Hildebrand Gurlitt’s complex story arises as one of the narratives that thread through both exhibitions. Having initially lost his job as a museum director in 1933 for refusing to fly the Nazi flag and for showing works by German Expressionists, Gurlitt went on to open his own dealership, registered to his wife because he himself was a quarter Jewish. But only a few years later, he was able to deal in “degenerate” art on behalf of the Nazis.

The Bern show boldly asks whether Hildebrand in fact contributed to the preservation of many of the works in the show. A drawing by Kirchner, Zwei Akte auf Lager (1907-8), for example, failed to sell at the notorious 1939 Lucerne Auction—where important artworks went under the hammer for well under their market value at the time—so Hildebrand acquired it for his own private collection. Many other works that he bought from the auction are now at the Kunsthalle Bern as well.

Both exhibitions also highlight the stories of the victims, be it artists like Kirchner, who committed suicide in 1938, or the families and other Jewish dealers who were forced to sell, or whose collections have been Aryanized. “There’s always a slight chance that a work seized from a German museum was on loan from a private Jewish collection,” says Nina Zimmer, director of the Kunstmuseum Bern and the affiliated Paul Klee Center, about the works on view in Bern. “Until we have confirmed that the state confiscated the museums’ own property” she says, the provenance is still considered unclear.

The Case of Two Paul Klees

Paul Klee, Greeks and Barbarians, (1920) ©Kunstmuseum Bern, Bequest of Cornelius Gurlitt

For the Bern museum, which also managed the Paul Klee Center, the discovery of two works by Klee in the trove was uniquely important. “Because Klee kept his own catalogue raisonné, we knew these works existed, but only that they were in a private collection,” says Zimmer. Finding them here “was a dramatic moment,” she adds. Their provenance, like that of 112 additional works on view in Bern, is unclear. It’s known that they were confiscated from a museum, and later bought by Hildebrand from the private collection of a German museum director. How the director was able to purchase them is the one missing link.

Transparency in regards to the provenance research is also an important element in both exhibitions, and each work’s current status and any known information on its lineage are indicated in the wall texts. Ellipsis in parentheses, symbolizing gaps in a work’s history, populate numerous tags.

Interestingly, one of the Klees, titled Greeks and Barbarians, was a work that Adam Szymczyk was particularly interested in displaying at this year’s documenta 14, given the titular link to the quinquennial that took place in Greece and Germany. (Works from the Gurlitt trove would have gone on view in Kassel if it wasn’t for the lawsuit by Cornelius’s cousin, who contested the validity of his will.)

Works of Unclear Provenance on View in Bonn

The German Minister of Culture, Monika Grütters, allocated €6.5 million ($7.6 million) for provenance research undertaken by a special task force headed by Andrea Baresel-Brand. So far, six works have been identified as Nazi-looted; the research’s funding ends at the end of the year.

Of the entire trove, 1039 works are being researched. Of these, 735 need additional “deep research,” meaning there are gaps in their provenance, their authorship is indecisive, or there are several versions of the same work, so there’s a need to dig further. Despite the gaps, 464 of the works in “deep research” don’t have any clear evidence of being Nazi loot, and 152 are marked as possibly looted works. For hundreds of works, including a piece by Cézanne titled La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, the research is still ongoing.

Some 250 of these works are on display in Bonn. By the end of the year, it is possible that several might be labeled as looted. What will happen to those works, however, is unclear; they will most likely remain in Germany, as the Federal Government came to an agreement with Bern that only non-contaminated works can go to Switzerland.

Lucas Cranach der Jüngere, Workshop, The Christ Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist (1540?) ©Bundeskunsthalle Bonn

To illustrate the difficulty in handling looted works, the show in Bonn includes pieces on loan from other German institutions labeled “Collection of Federal Republic of Germany”—an indicator of works that are proven to be looted art but impossible to restitute, as there are no heirs or claimants. One such example is an oil painting by Peter Paul Rubens from the collection of the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, The Saints Gregory, Maurus, Papianus and Domitilla, from after 1606.

The exhibition in Bonn also includes works by Old Masters, Impressionists, and Modernists found in Gurlitt’s collection, including Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. “The importance of the Gurlitt Case is in the new impetus it gave to provenance research,” says Rein Wolfs, director of the Bundeskunsthalle. “There’s still a lot more to research, and more could have been done before.”

The discovery of the hoard made provenance research a political cause, and funds—both public and private—suddenly became available. The Kunstmuseum Bern for example has received considerable grants for the analysis of its entire existing collection.

Albrecht Dürer, Knight, Death and Devil (1513) ©Bundeskunsthalle Bonn

How Much Had Been Known?

As the task force’s Andrea Baresel-Brand points out, Cornelius Gurlitt is the first and so far only private person to have submitted his private collection to be investigated in compliance with the rules of the Washington Principles on Nazi-Looted Art from 1998. Whether or not he was fully aware of what’s in his hands, or whether he was convinced the works legally belonged to him, is still somewhat of a mystery.

What’s certain however is that his father, Hildebrand, successfully rehabilitated his name after the war, presenting himself as a victim of the Nazi system, and became wholly de-Nazified. By 1948, he was able to work as museum director again.

“For many decades, everyone in the art world knew who Gurlitt’s father was, what he did, and how he managed this huge collection and great wealth after the war—that was no secret,” said Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress and chairman of the Commission of Art Recovery, in a video statement. The exhibition in Bonn includes many handwritten notes and other indications of the extent of the coverup perpetrated by Hildebrand, who claimed that his collection perished in a fire in 1945. Displays including false affidavits, coded exchanges with dealers after the war, and one of the few original editions of the French registry of looted art—the Repertoire de Biens Spoliés comprised by Rose Valland—that was in the family’s possession, make this unambiguous.

Of the many big open questions that persist after viewing both shows—including the question of the fate of those works whose provenance remains unclear—some are more troubling than others. How was it possible for this trove to go ignored for over half a century? And how many works have been dealt with on the private market, undeterred by their questionable provenance?