It has been 20 years since the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art were declared to support the restitution of stolen art in 1998, but many lawsuits continue to drag on. Though progress has undoubtedly been made, the principles are non-binding, and many families have still not received the justice they seek.

This week, to mark the anniversary of the international agreement, the German Lost Art Foundation is holding a conference in Berlin (November 26–28) to assess the effectiveness of the Washington Principles and determine how countries might better adhere to them. As noted by the Art Newspaper, only five countries—the UK, the Netherlands, Austria, Germany, and France—have set up dedicated panels to rule on disputed artworks.

Stuart E. Eizenstat, an adviser to the State Department who hosted the 1998 Washington Conference that drew up the principles, estimates that some 600,000 works were stolen during the war, and that 100,000 are likely still missing. He told the New York Times that Hungary, Italy, Russia, Poland, and Spain are the five countries that have made the least effort toward upholding the Washington Principles and returning looted works.

Ronald Lauder, head of the World Jewish Congress, is also calling on other countries to step up when it comes to Nazi restitution. France, for instance, still hasn’t determined the rightful owners of some 2,000 works that were never claimed after the war and now reside in national museums.

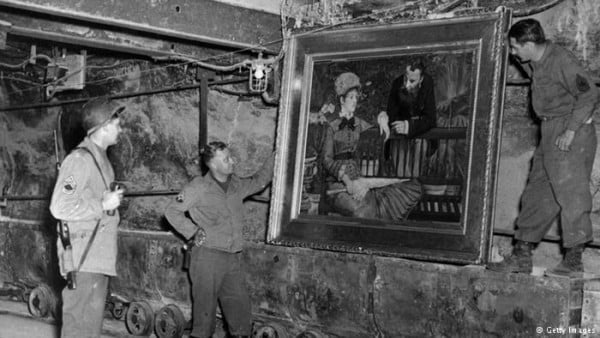

American troops unpack art confiscated by the Nazis, including this Johannes Vermeer forgery. Photo courtesy of the Institute of Museum Ethics.

Germany’s culture minister, Monika Grütters, told the Associated Press that it’s Germany’s responsibility to better fulfill the Washington Principles, saying that “behind every stolen object is the fate of an individual.”

Because institutional and bureaucratic obstacles often delay the restoration of looted cultural objects to their Jewish owners or heirs, Grütters has pledged to set up a special “help desk.” This will increase research into finding heirs, upload more information about Germany’s collections online, and allow heirs to seek restitution from a museum without the museum’s agreement.

“There is simply no excuse in the 21st century for coveting Nazi-looted art,” Eizenstat told the AP, “and it does not speak well for the countries that do so.”