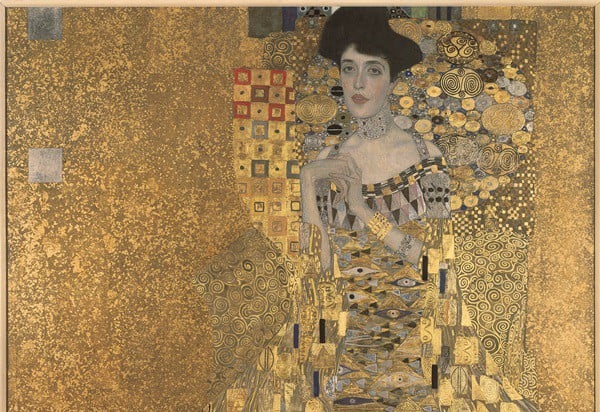

Nine years ago, when cosmetics magnate and top collector Ronald Lauder, co-founder of the Neue Galerie, shelled out a reported $135 million for Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), many in the art world were stunned (see Why Ronald Lauder is Right About Nazi-Looted Art in Museums).

At that point, only one work had ever sold for more than $100 million at auction—according to public records—and that was Picasso’s undeniable Rose-period masterpiece Boy With a Pipe (1905) sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2004. No one cast any doubt on that landmark price. Not only was Picasso considered one of the best artists in the world—if not the best—that particular masterpiece also came with a sterling provenance. It had been tucked away in the blue chip collection of John Hay and Betsy Whitney for decades. The Whitneys had acquired the work for $30,000 in 1950.

Prior to that, the highest price for a work at auction was $82.5 million, paid in 1990 by a Japanese collector for Vincent Van Gogh’s 1890 Portrait of Dr. Gachet at the then-peaking art market (see 10 Game Changing Auctions and Do Riches Await In The Van Gogh Market?).

How, market observers and art experts wondered aloud, had it been possible for Klimt—the Austrian Secessionist whose particular style was not exactly everyone’s cup of tea—managed to vault to four times more than his previous record of $29.3 million and far outstrip both of the records for heavyweights like Picasso and Van Gogh.

In a New Yorker column in July 2006, critic Peter Schjeldahl said: “Is she worth the money? Not yet. Lauder’s outlay predicts a level of cost that must either soon become common or be relegated in history as a bid too far. And the identity of the artist gives pause…. Until a few years ago, the artist ranked as a second-tier modern master.”

In a phone interview with the late Robert Rosenblum at the time, he told me that looking at Klimt, whose work he personally liked, was “like going to a Viennese bakery.”

Klimt’s Portrait of Adele I was one of five paintings restituted to the heirs of Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, a wealthy sugar magnate whose wife Adele was the subject of the portrait. Nazis stole the works off the Bloch-Bauers’ walls in 1938 after Germany annexed Austria. Bloch-Bauer eventually fled the country. And the Belvedere Gallery eventually came to hold the works, citing a 1923 will by Adele (who died in 1925) that she had bequeathed the paintings to the institution (see Weinstein’s Nazi-Looted Klimt Restitution Film to Star Helen Mirren).

Maria Altmann, one of Bloch-Bauer’s heirs, fought for the return of the paintings for eight years and was ultimately successful in her efforts. She died in Los Angeles at age 94, in 2011. The story is now the subject of a major Hollywood film, Woman in Gold, that opened April 1 and stars Helen Mirren as Altmann and Ryan Reynolds as her lawyer E. Randol Schoenberg.

The Neue Galerie has just opened an exhibit devoted to the history of the painting, timed to coincide with the movie, including archival material, sketches, jewelry, and other Klimt paintings (see Gustav Klimt’s Real Woman in Gold Goes on View at the Neue Galerie).

In 2006, I interviewed Lauder and others about the acquisition and reported on the process for a story that appeared in ARTnews magazine in 2007. Lauder talked about his particular passion for the work of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele. Of the price for Adele I, Lauder told me in a phone interview “I didn’t even think of that. I knew there was nobody who wanted the painting more than me.” He called Adele I, “a once in a lifetime opportunity,” and has described it as the Neue Galerie’s Mona Lisa.

Lauder said he first saw Klimt’s at age 14 on a trip to Austria. After traveling with his family in France, he said he went on his own specifically to see the Klimt paintings that were hanging in the Belvedere. He described it as “like finding the Holy Grail. I was actually blown away by it. I had never seen such powerful images as The Kiss and Adele I.”

At a time when the art world seemed obsessed with Claude Monet and French Impressionism, Lauder said there was “an excitement of discovery,” about Schiele and Klimt, because no one else he knew seemed to know about them.

Some market observers said it was wrong to view the $135 million price as a battle of sorts between Klimt and Picasso. They said that the legendary backstory of the Adele portrait put the work on another plane altogether.

Members of the $100 Million Club

Artworks that have sold for more than $100 million each at auction.

Of course, in the years since Lauder made his purchase—which was transacted privately with the help of Christie’s and does not appear in the artnet Fine Art & Design Price Database—several other world-class artists have joined the so-called $100 million auction club, including Francis Bacon, Edvard Munch, Andy Warhol, Alberto Giacometti (twice), and Picasso, who hit that mark a second time again in 2010.

There have also been some private sales that exceeded the $100 million mark, including Paul Cezanne’s Card Players to the nation of Qatar for $250 million in early 2012. More recently, an 1892 painting by Paul Gauguin of a Tahitian scene, Nafea Faa Ipoipo (When Will You Marry?) sold to a museum in Qatar for a whopping $300 million. (See Paul Gauguin Painting Sells for $300 Million to Qatar Museums In Private Sale.)

Early on, most Americans gave Klimt and Schiele the cold shoulder. As I reported in my 2007 story, following a 1956 show of works by Klimt and Schiele at the Guggenheim Museum, one critic, Anthony West, writing in the Washington Post, called the exhibition “an attempt to float two Viennese second-raters.” He described some of Klimt’s later works as “dottily erotic.” He said The Kiss and other Klimt works showed “the essence of the vulgar fraud that his ‘art’ truly was.”

So where does the art world currently stand on Klimt?

Schjeldahl has turned even more negative on Klimt as evidenced by a 2012 column in The New Yorker, titled “Changing My Mind About Gustav Klimt’s Adele.” Said Schjeldahl: “It’s not a painting at all, but a largish, flattish bauble: a thing. It is classic less of its time than of ours, by sole dint of the money sunk in it.” Schjeldahl said the painting “makes no formal sense,” adding: “The size feels arbitrary, without integral scale in relation to the viewer: bigger or smaller would make no difference.”

Nevertheless the hype surrounding the 2006 sale of Adele I, clearly had a buoyant effect on the Klimt market. The four other paintings that were returned to Maria Altmann from the Belvedere, were sent to auction at Christie’s New York in November 2006 and all sold well over estimate.

Gustav Klimt, Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912). Private collection. © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

Adele Bloch-Bauer II, painted in 1912 (and the only instance in which Klimt painted the same subject twice), soared to $87.9 million at the 2006 sale, on an estimate of $40–$60 million, again outstripping the Van Gogh record of $82.5 million set in 1990. The private collector who acquired it has loaned the work to the Museum of Modern Art (see Nazi-Looted Gustav Klimt Portrait Debuts at MoMA).

The remaining three works all sold well: Birch Forest (1903), sold for $40.3 million; Apple Tree I (circa 1912), sold for $33 million; and Houses at Unterach on the Attersee (circa 1916) sold for $31.4 million.

In all, the restituted works, including Adele I, achieved $327 million. Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight said at the time: “The whole brouhaha over the sale of Adele I did nothing but enhance the market value of the remaining works.”