Art World

Haitian Art Is Coming Into the International Spotlight. It’s Not the First Time

The nation's artists are winning high-profile show and Venice Biennale appearances—and their prices are rising.

When Haiti makes headlines in the American press, the news is all too often tragic: catastrophic earthquakes in 2010 and 2021, the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, the recent takeover of swathes of the country by gangs.

While no art world developments could possibly ameliorate these crises, it is, at least, heartening to see that Haitian art has been gaining newfound attention throughout the U.S. and Europe, with museum spotlights, gallery shows, and rising market interest.

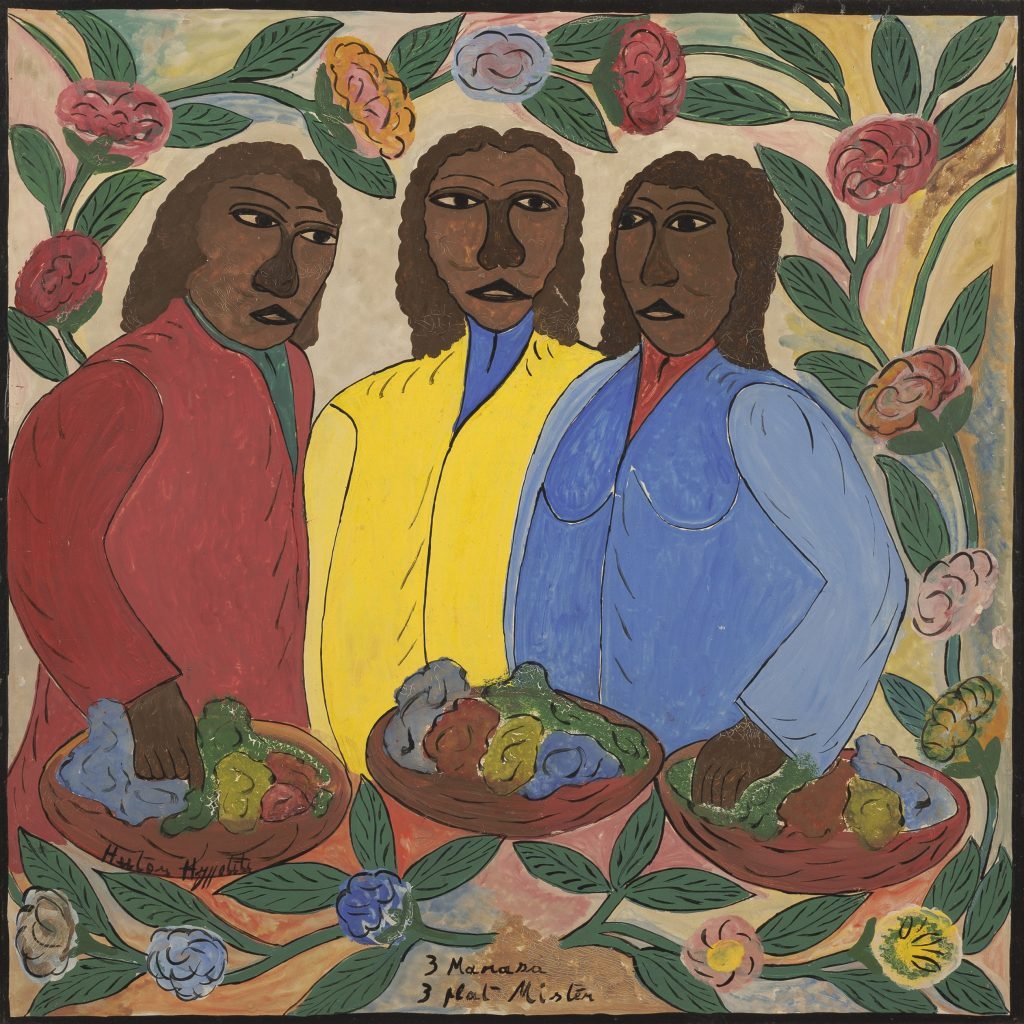

Hector Hyppolite, 3 Marassa (1947). Photo: Luke Christopher, courtesy National Gallery of Art.

Perhaps the most prominent example is the exhibition “Spirit & Strength: Modern Art from Haiti,” now running at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. It features 21 pieces, including 15 recently donated to the museum—the first Haitian artworks to enter its holdings. (For nearly a century, the institution has also funded artists’ travel to the island nation, made possible by a fund established by founding benefactor Lessing J. Rosenwald.)

The show’s curator sees the new wave of attention for Haitian art in the context of the art world’s recent attempts to highlight those who have been left out of the art-historical canon.

Myrlande Constant, Guede Djable 2 Cornes (not dated). Courtesy National Gallery of Art.

“Since the racial reckoning that happened in 2020, when many former colonial powers started to reassess and think about whose voices need to be heard, there have been a lot of recovery and rediscovery projects, with new attention to women and Black artists,” Kanitra Fletcher, the museum’s associate curator of African American and Afro-diasporic art, said in a phone interview.

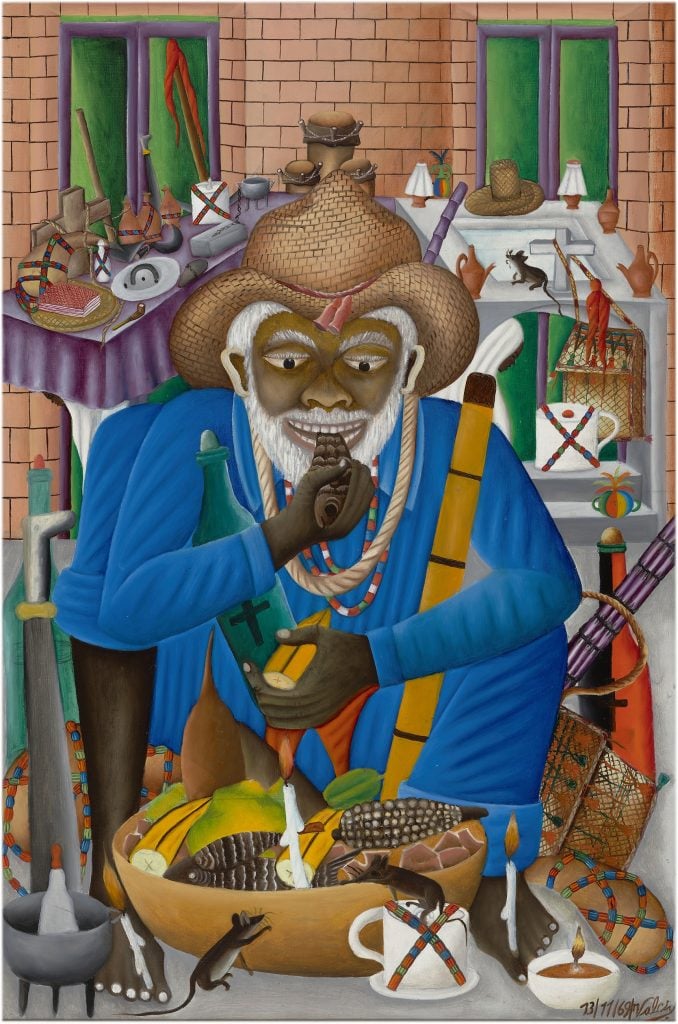

The exhibition starts in the mid-20th century, when there was a flourishing of Haitian art, with globally known artists like Hector Hyppolite, Rigaud Benoît, and Philomé Obin, and extends to a later generation that they influenced, including Lois Mailou Jones and Eldzier Cortor. Some are academically trained while others are self-taught or learned their craft through informal networks such as their families. Many have sought to create an artistic identity there that is free from the influence of the United States, Fletcher pointed out. The Centre d’Art was established in Port-au-Prince in 1944 as an art school and gallery, and it became the center of what is now known as the Haitian Art Movement. Artists coming from academic and non-academic traditions met and learned from one another, she said, creating a complex mix.

Philomé Obin, President Tiresias Sam Entering Cap-Haïtien (1958). Courtesy National Gallery of Art.

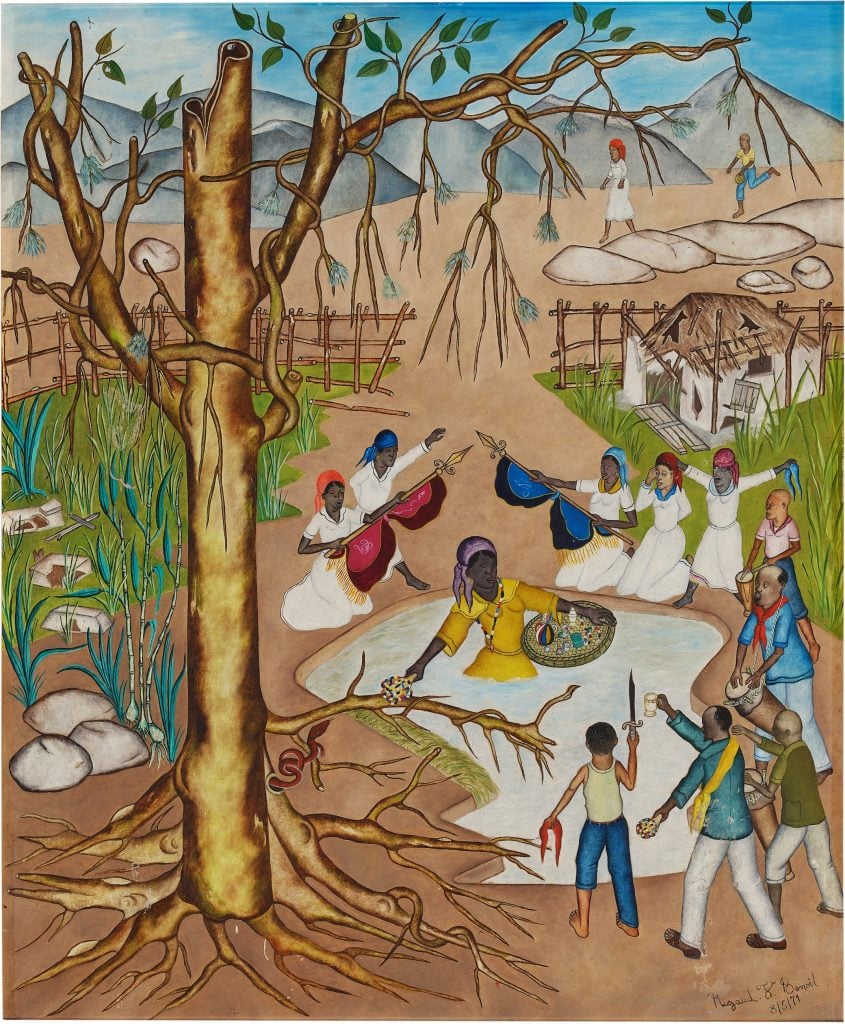

The show’s works range widely in subject. There are history paintings, such as Philomé Obin’s President Tiresias Sam Entering Cap-Haïtien (1958), scenes of everyday life, like Rigaud Benoit’s Marketplace (1965), and pieces inspired by Vodou traditions, including Myrlande Constant’s drapo Vodou, or Vodou flags; her undated work Guede Djable 2 Cornes shows a hybrid bat/man figure holding aloft a sword and a head. The Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott gave the show a rave review.

Gérard Valcin, Papa Zaca (1969).Photo: Luke Christopher, courtesy National Gallery of Art.

The museum also included Haitian artists in “Afro-American Histories,” a show it co-organized with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museu de Arte de Sāo Paulo, which traveled among the three venues from 2021 to 2024. Among its 130-plus works were examples by artists with Haitian roots, like Firelei Báez, Castera Bazile, Denis Emile, Philomé Obin, Seneque Obin, and Georges Valris. (Fletcher also curated the show’s U.S. leg.)

Individual artists are getting museum recognition as well: last year, the Fowler Museum at the University of California, Los Angeles, mounted the retrospective “Myrlande Constant: The Work of Radiance,” which it billed as the first U.S. museum show devoted to the work of a Haitian female contemporary artist.

A Long History, Coming Up to the Moment

Haiti was founded in 1804 as the world’s first Black republic after a successful slave uprising against the French that kicked off in 1971, and this isn’t the first time its rich artistic tradition has gained the eyes of outsiders.

No less perceptive a figure than Surrealist capo André Breton wrote in a comment in the visitors’ book at the Centre d’Art during his 1945-46 visit (with reference to the leader of the revolution), “Haitian paintings will drink the blood of the phoenix. And, with the epaulets of [Jean-Jacques] Dessalines, it will ventilate the world.” The poet was invited to give a series of lectures in Port-au-Prince by his friend Pierre Mabille, the French cultural attaché to Haiti. In a 1945 interview he said, “Surrealism is entirely in league with peoples of color… because of the profound affinities that link the so-called ‘primitive’ mind with surrealist thought.” (It’s true that as seriously as he may have taken their art, Breton’s framing has not aged well.)

So in a sense, it’s fitting that a wave of interest in Haitian art should coincide with fresh attention to Surrealism on its 100th anniversary. The connection between Haiti and the art movement was the subject of the exhibition “Surrealism and Us: Caribbean and African Diasporic Artists since 1940,” which closed recently at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Texas. Curated by María Elena Ortiz, that show included Haitians like Rigaud Benoit, Constant, Cortor, Préfète Duffaut, Paul Gardère, Hyppolite, André Pierre, and Hervé Télémaque. The Fort Worth Weekly splashed the show on its cover and proclaimed that it had “a brilliantine, important message for today.”

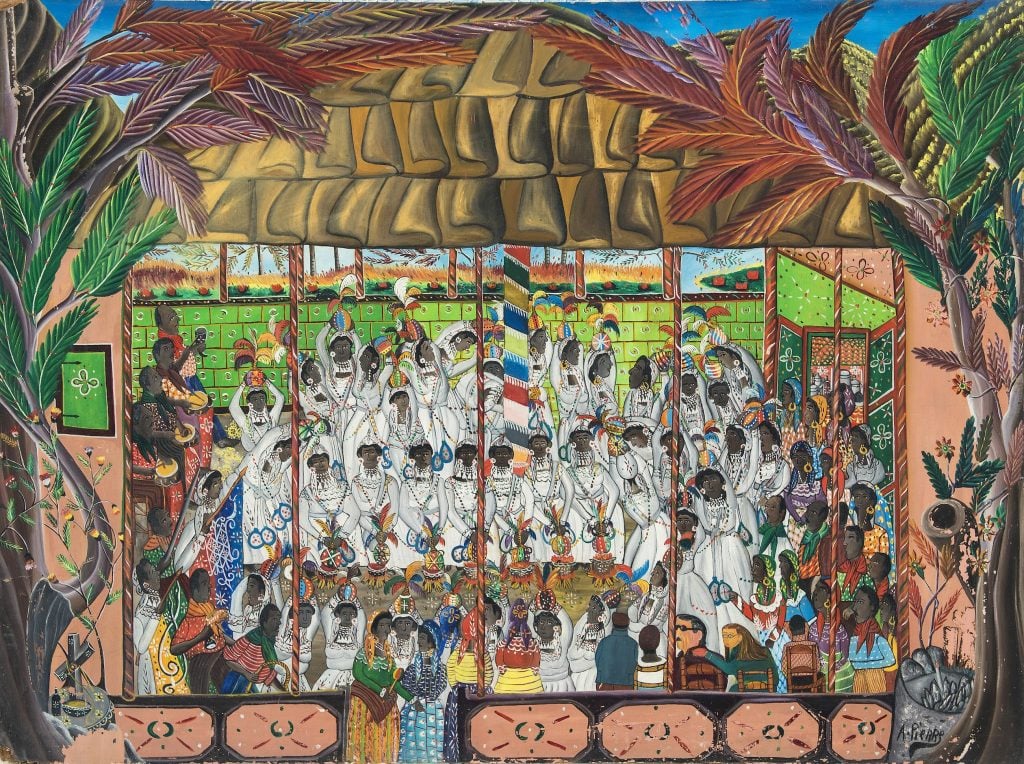

Sénèque Obin, Reception Marriage Interieur (1966). Photo: Matteo de Mayda. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

The main exhibitions of the last two Venice Biennales have also provided major stages for Haitian artists. Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 show, “The Milk of Dreams,” included multiple tapestries by Constant. Adriano Pedrosa’s just-closed “Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere” included the brothers Philomé Obin and Seneque Obin. (Pedrosa was also a curator of “Afro-American Histories.”)

Philomé Obin, Habitiacion Bayuex (ca. 1957). Photo: Matteo de Mayda. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Over in France this month, the French-Haitian artist Gaëlle Choisne won France’s largest prize for artists, the Prix Marcel Duchamp. Administered by the Association for the International Diffusion of French Art, it comes with a grant of €35,000 ($38,000) and a two-year residency at the porcelain factory Sèvres–Manufacture and Musée Nationaux. Her work appears in the current Gwangju Biennale and was part of the 2021 New Museum Triennial in New York.

Gallery Shows in a Nerve Center of the Art Market

Haitian art is also getting a market spotlight in some New York exhibitions.

“Ayiti Toma II: Faith, Family, and Resistance” at Luhring Augustine is an intergenerational show that includes artists from Hyppolite to Constant. It’s organized by Haitian-born artist Tomm El-Saieh in partnership with El-Saieh Gallery of Port-au-Prince (founded by the artist’s grandfather, musician-composer Issa El-Saieh), and Central Fine gallery of Miami Beach, Fla., where he is also one of the principals. The title translates as “land of the high mountains/From now onward, this land is our land.” Ayiti in the Taíno language means “land of the high mountains” and was the Taíno name for Hispaniola, which was chosen by the Haitian people upon their independence from France. According to El-Saieh, the origins of Toma are harder to pinpoint but, according to lore, it is the “last name” of the country.

André Pierre, Untitled (no date). © André Pierre; courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and El–Saieh Gallery, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Ralph Dupoux.

The strife in El-Saieh’s home country has affected the show, he said in a phone interview. Some works that were supposed to be included got stuck in Port-au-Prince, when the port was closed after gangs opened fire on the boats there.

He wouldn’t even say that this current moment for Haitian art represents the greatest case of international recognition, referring instead to Breton’s time there as the high-water mark, along with contemporaneous attention to Haiti by none other than New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Two researchers point out in a post on MoMA’s website that curator René d’Harnoncourt (later the museum’s director) bought René Vincent’s 1940 painting Le combat des coqs (Cock Fight) from the artist, and the museum bought it from him in 1944; it was the first work of Haitian art to enter the museum’s collection.

Jean Hérard Celeur, Zwazo 2019. © Jean Hérard Celeur; courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and El-Saieh Gallery, Port-au-Prince.

“What Haiti proves is art’s amazing ability as a tool for survival,” El-Saieh said. “Myrlande, for example, has made all her recent works, including the works that were in the Venice Biennale, through this political strife. Her career has oddly blossomed through this and it’s been able to save her life and her family’s life, because it gives them something to work towards.” And yet, he pointed out, the artist was unable to get visas to see the Venice exhibition and the Fowler retrospective.

A Haitian artist was also the catalyst for a show that Wayne Northcross recently staged at New York’s Canada gallery, where he is director of museum and institutional relations. The show dealt with African American contemporary art’s links with religious and spiritual practices, looking at how works are invested with spiritual meaning. When he encountered the work of the Port-au-Prince–born, New York–based Paul Gardère (1944-2011), who painted symbols and figures from Haitian Vodou traditions, it all started to come together.

“Charismatic Goods” at Canada Gallery, with Paul Gardère, Untitled (1986), left, and Rubem Valentim, Emblema 87 (1987), right.

The show, “Charismatic Goods,” featured an intergenerational group of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx artists, including Patrisse Cullors (also known as a co-founder of Black Lives Matter) and Xaviera Simmons. In an untitled 1986 work, Gardère distilled images of three important Vodou cosmic figures: Damballah (snake), Grand Bois (bough), and Legba (curved staff). Other artists in the show traveled through Haiti, Northcross said in a phone interview.

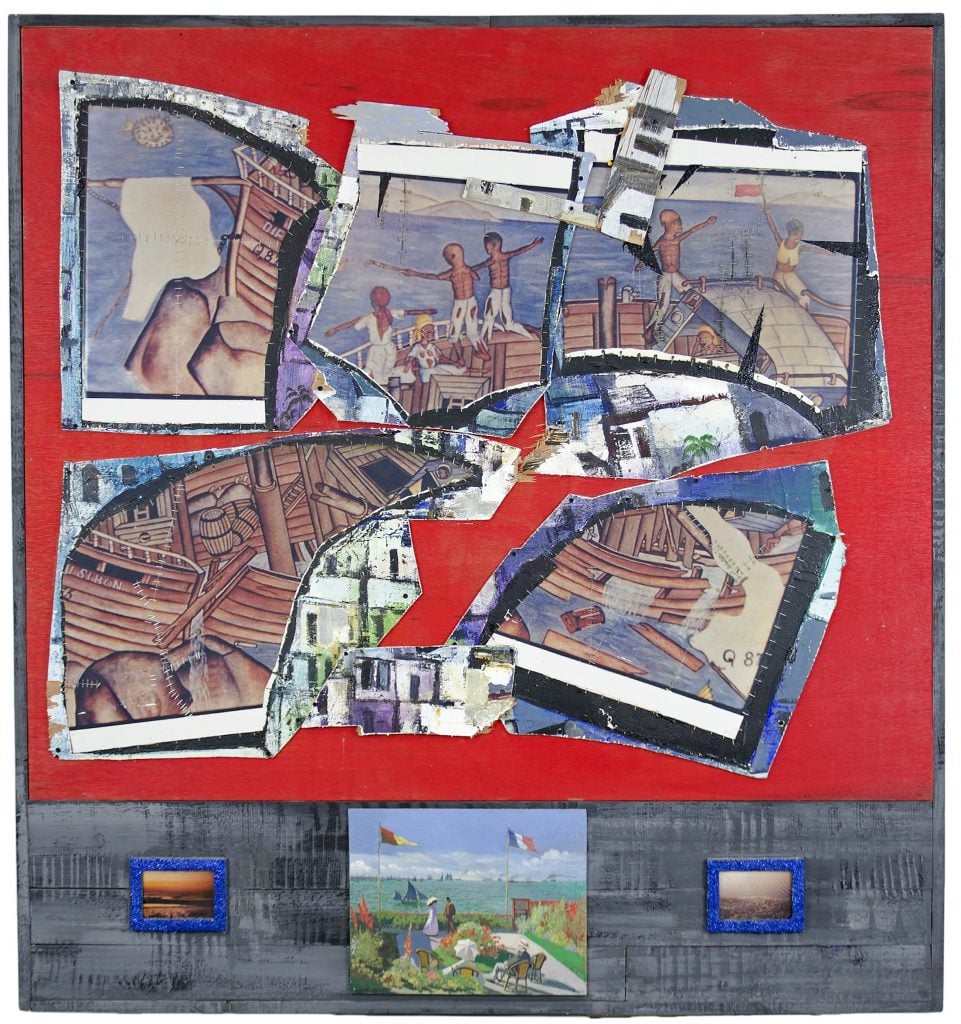

Paul Gardère, Triplex Horizon (1998). © The Estate of Paul Gardère.

Gardère is also the subject of a solo show at New York’s Cooper Union, where he earned a BFA before going on to earn an MFA from Hunter College in the city. “Paul Gardère: Vantage Points,” at the landmark Stuyvesant-Fish House, spans his work from the early 1970s to the late 2000s, with some focus on the legacies of colonialism.

For example, his work Triplex Horizon (1998), which prominently features the colors of the Haitian flag, puts a torn and collaged reproduction of Haitian artist Rigaud Benoit’s work Shipwreck (1965) in dialogue with both Claude Monet’s idyllic rendering of bourgeois leisure in his famed painting Garden at Sainte-Adresse (1867) and two photographs of the American coastline.

A Modest but Rising Market—and an Attempt to Send Help

Relative to many other sectors of the market, prices for Haitian artists remain modest, but notwithstanding some ups and downs, their works have performed increasingly well at auction since 2014, according to data from the Artnet Price Database. In that year, for example, 56 lots sold for a total of $457,000. Through October 2024, the greatest volume of works in the past decade had sold: 169 examples, generating that stretch’s highest total, $1.4 million.

Several individual artists’ auction markets have taken off in recent years.

Nine of Hyppolite’s paintings have exceeded the $100,000 mark at auction, all of them since 2020 and five of them in 2024. His current record is for the ca. 1947 painting Damballah La Flambeau (also known as Aida-Quédo and The Snake Goddess Ayida-Wedo), which exceeded its $250,000 high estimate to fetch $365,400 at Christie’s New York in 2022.

Hector Hyppolite, Damballah La Flambeau (also known as Aida-Quédo and The Snake Goddess Ayida-Wedo) (ca. 1947). Courtesy Christie’s.

Rigaud Benoit is also ascendent. His top three prices have come since October of 2023, the year his auction record was set with the 1971 painting Cérémonie sous le Mapou, which sold at Sotheby’s New York in for $69,850, nearly eight times its high estimate. While his work generated only $2,318 at auction in 2018, it rang up $117,075 in 2024 through October.

Rigaud Benoit, Cérémonie sous le Mapou (1971). Courtesy Sotheby’s.

New York dealer Michael Rosenfeld, of the eponymous Chelsea gallery, got interested in Haitian art as a result of his grandfather buying a Hyppolite painting while traveling the country on business in the mid-20th century. He cited 1978 Brooklyn Museum exhibition “Haitian Art” as yet another forerunner of today’s wave of interest.

Rosenfeld said that, relative to the quality of and interest in Haitian art, prices remain modest. Besides Hyppolite, he also owns works by Préfète Duffaut, the Obin brothers, André Pierre, and other major figures. “I find it puzzling, frankly,” he said in an interview. “These are extraordinary works by extraordinary artists.”

One market player, New York–based Haitian-American advisor Gardy St. Fleur, who collects Haitian art, has tried to use art to help people in his homeland by bringing together his passions for visual art and basketball. He organized a 2021 Phillips sale, “The Crossover,” to benefit Project Backboard, a non-profit organization that works with artists to turn public basketball courts into community spaces; the funds were planned to go to build Project Blackboard’s first international project, in Haiti. The sale included established figures like Deborah Roberts and emerging talents like Milo Matthieu.

“The country has been through so much,” said St. Fleur, who has not yet delivered the proceeds from the sale. “I still haven’t been able to make it there because things are so bad.”

“Spirit & Strength: Modern Art from Haiti” is on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., through March 9, 2025. “Ayiti Toma II: Faith, Family, and Resistance” is on view at Luhring Augustine in Tribeca through January 11, 2025. “Paul Gardère: Vantage Points” is on view at Stuyvesant-Fish House through June 6, 2025.