Law & Politics

No, Crediting the Artist Is Not ‘Enough’: The Case of Hallie Bateman Reveals How Online Exposure Can Be Tough for Artists

The unauthorized use and dissemination of artists' work is especially rampant online.

The unauthorized use and dissemination of artists' work is especially rampant online.

Sarah Cascone

In recent years, for-profit companies from HBO to H&M have been caught using artworks without their creators’ permission. But in one recent case, the copyright infringer is a Belgian art foundation and art center, the Stichting Ijsberg in Damme, which used the work of Los Angeles artist Hallie Bateman to promote its exhibition—even after she had specifically declined to participate in the show.

The incident, which sparked condemnation of the foundation on social media—their most recent Instagram post has just 57 likes, but 869 angry comments, as of press time—is illustrative of a common problem for artists and creators. As Bateman has learned more than once, artwork can be widely disseminated online without crediting the original source, let alone compensating them.

When another artist informed Bateman that the art center was promoting an exhibition using her work, “I felt annoyed and exhausted, especially when I discovered they’d asked and I’d actually said no,” Bateman told Artnet News in an email.

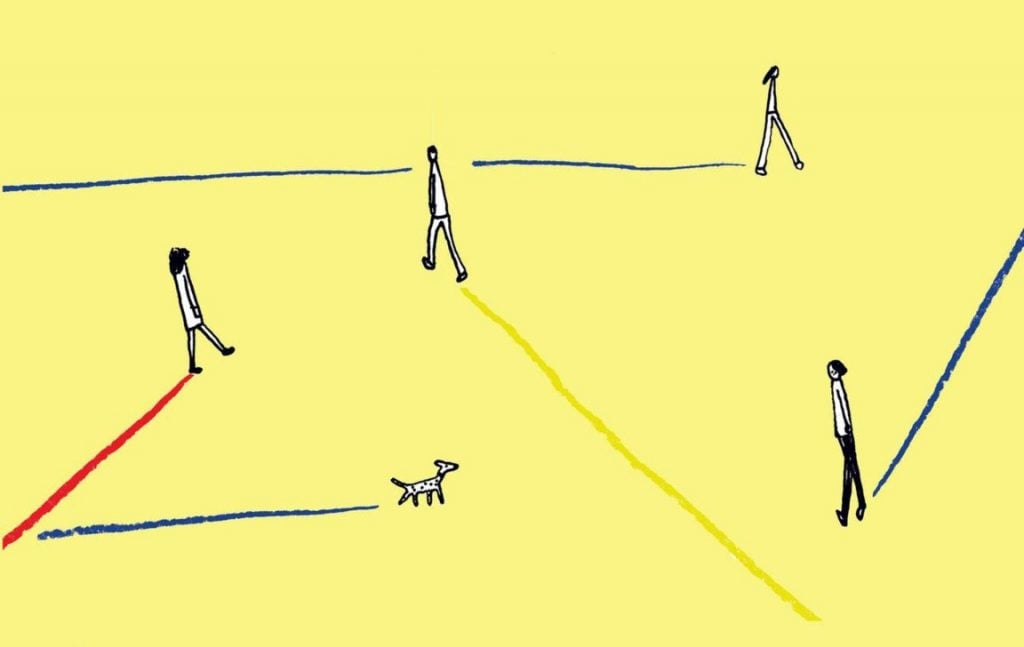

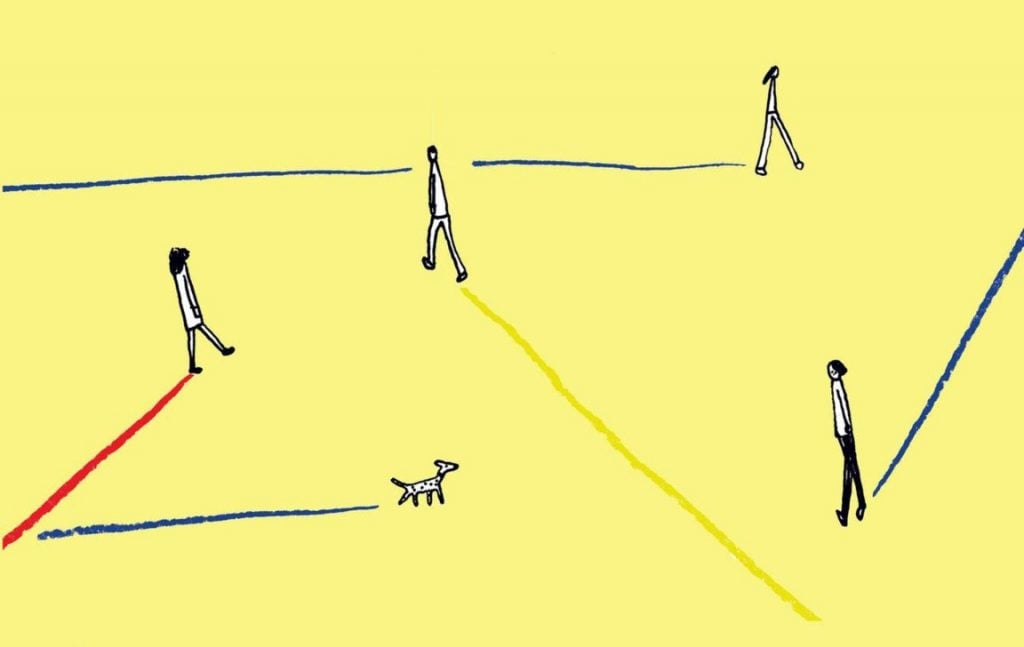

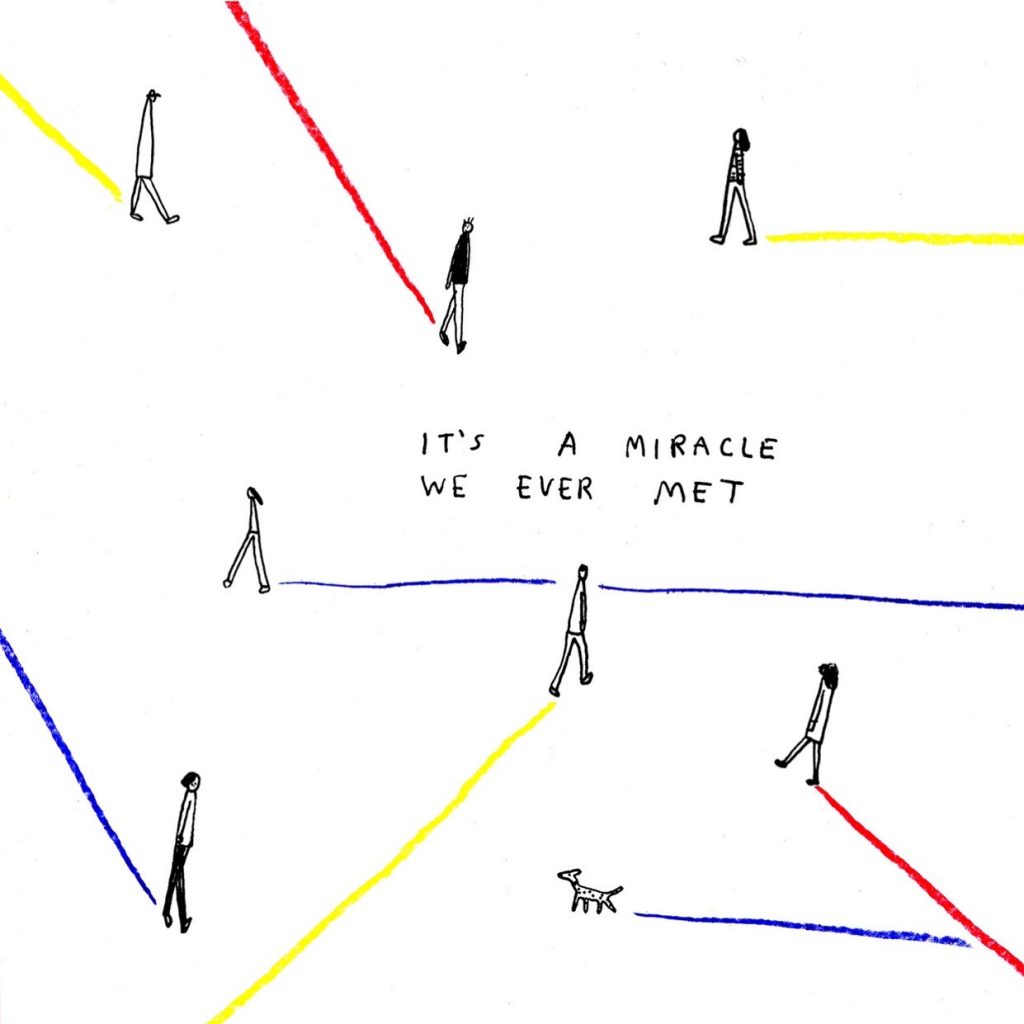

It’s a miracle we ever met (2016) is a simple line drawing in crayon of people walking across a blank white page, colored pathways trailing behind them, illustrating the unlikelihood of two people’s lives ever intersecting. Stichting Ijsberg had contacted Bateman in March, asking to use the piece in a July show about the arbitrary nature of human connection. She initially declined, and did not respond further when the organizers followed up to see if they could agree on a fee for the use of the work.

Undeterred, Stichting Ijsberg bought a $45 print, scanned it, gave it a yellow background, and used it in all their promotional materials for the show. After Bateman found out last month, she spoke out on Instagram. The story was picked up by Belgian paper De Standaard, and then in English by Fast Company.

“When this happens (and it happens a lot) I feel confused,” Bateman said. “It’s a mindfuck, specifically with this piece. It’s all about the power and sacredness of human connection, and it’s being taken from me by people who don’t give a shit about me or want any connection with me. It boggles my mind that people can look at the drawing, be struck deeply by it, and at the same time have zero curiosity about its origin.”

Stichting Ijsberg did not respond to inquiries from Artnet News, but its defense to angry internet commenters has been that it properly credited Bateman as the artist. That doesn’t mean it had the right to use the work.

“The gallery may own a print of one of the artist’s works, but it doesn’t own the underlying copyright in the work. Ownership of a physical work of art is separate and distinct from ownership in the underlying copyright,” Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, told Artnet News in an email. “As the owner of the copyright, the artist has nearly absolute control over the way the work is employed.”

It’s a miracle we ever met is a deeply personal work for the artist, one that makes her think back to a moment she shared with her younger brother a couple of years before she made it.

“We sat on a big rock together, looking out at the ocean,” Bateman wrote. “I remember it suddenly felt like we weren’t kids any more. It hit me so hard how unlikely and frankly insane it was that this spirit, this kind, funny, weird brother of mine, existed. And that we both got dropped into bodies not just in the same century and continent but FAMILY.”

Hallie Bateman. Photo: Meredith Adelaide. Courtesy of Hallie Bateman.

“This is usually how my art comes out. It starts as a truth or an emotion or an idea. It hits my head and my heart all at once. It’s this tingling all-body epiphany,” she added. “It’s not a straight line from that moment with my brother to the Miracle drawing. But it’s the moment I think of when I look at it.”

She isn’t surprised the artwork, and the emotion behind it, has resonated with so many people.

“It enables you to see life through this lens of gratitude and awe and incredulous wonder—’What are the odds?!’” Bateman said.

She has also been moved by the support she’s received online since the foundation was outed for the unauthorized use of her work.

“People are sharing the piece with tags and buying prints and leaving me kind, loving messages,” Bateman said. “I think publicizing this stuff, although it can be very draining and annoying, is helpful because it brings awareness to the importance of crediting and compensating artists.”

Hallie Bateman, It’s a miracle we ever met (2016). Image courtesy of Hallie Bateman.

Stichting Ijsberg did reach out to Bateman again, but she hasn’t responded.

“Their email was bizarre. Among other things, they offered to send me one of the flyers they printed to prove that they’d credited me, as if credit was the issue here,” she said. “They also said, ‘I understand that social media is being used to get attention for this issue. However, it would have been nice if you had addressed us through this channel first.’ That type of reaction is something I encounter again and again when I confront those who abuse my work. They always find ways to make themselves the victim.”

Artists who find themselves in similar situations can take steps to remedy the situation.

“When the artist discovers that their work has been used without permission, they can insist that the owner cease and desist from doing so, and demand that it be taken down,” Feder said. “Alternatively, the artist may choose to authorize the use in exchange for a fee that covers both past and future use. If the owner refuses to comply, recourse to the courts is available, but frankly is rarely employed because of the expense of litigation.”

“Additionally, it is important for artists to know that while copyright exists from the moment of creation, and requires no documentation for verification, in order to bring a suit to the courts, the owner of the copyright must first have the work in question registered with the copyright office,” Feder added.

The unauthorized use and dissemination of artists’ work is especially rampant online, where people can hide beyond anonymous usernames.

“Copyright is most often infringed upon in the digital space,” Feder said. “I think people are so quick to use artworks they’ve found online for two reasons: anonymity and lack of knowledge. Blockchain technology is trying—and to some degree slowly succeeding—at remedying this, but we are still some ways off from any standard being established or enforced.”

Bateman has begun signing her work—not just the individual prints she sells—but she isn’t sure how to convince the public of the importance of getting permission to use an artist’s work.

“Maybe ‘artist’ is a foreign idea to a lot of people,” she said. “Maybe we should be doing better PR and getting out there and knocking on doors.”