Law & Politics

University Settles With Professor Who Was Sacked Over Prophet Muhammad Artworks

Erika López Prater lost her job in 2022 after a Muslim student objected to seeing historic Muhammad artworks in class.

Erika López Prater lost her job in 2022 after a Muslim student objected to seeing historic Muhammad artworks in class.

Sarah Cascone

Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota, has reached a settlement in its religious discrimination case with former art history professor Erika López Prater.

The school had declined to renew her contract after a Muslim student complained about Prater’s inclusion of a historic artwork depicting Muhammad in the course. Many Muslims believe that it is forbidden to show the prophet’s face. But there is also a long history of devotional Islamic imagery that does just that—including works in the collections of institutions such as the Louvre in Paris, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

“It is important for scholars, students, and the general public to be aware of Islam’s diverse artistic heritage across the globe. For centuries, Muslim patrons and artists showed respect and devotion to the Prophet Muhammad not only through prayer but also in paintings, and this form of human creative imagination and expression cuts across all faiths,” Christiane Gruber, an art historian specializing in depictions of Muhammad who helped publicize Prater’s dismissal, told me in an email.

“Debate and disagreement in the classroom always offer openings for self-reflection and intellectual growth, sometimes even a change of mind. Hamline administrators should have activated this ethos—which is at the core of humanistic inquiry and the university’s prime raison d’être—by having discussed the matter constructively with the instructor and student,” she added. “It is a good sign that the instructor and Hamline University have found common ground to settle the matter.”

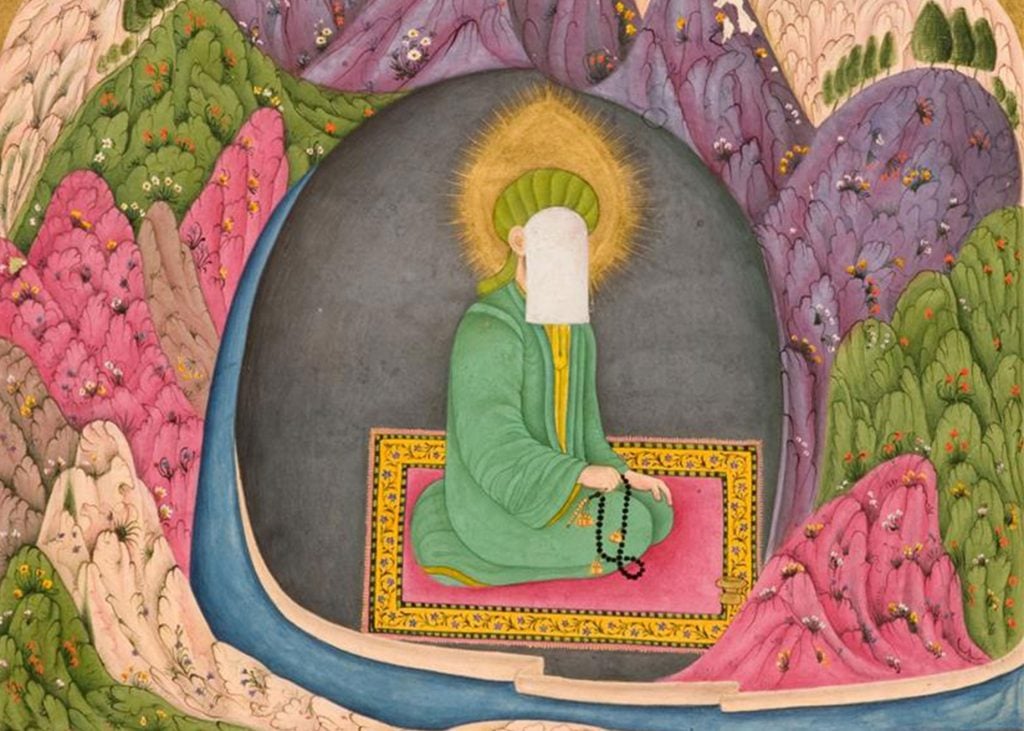

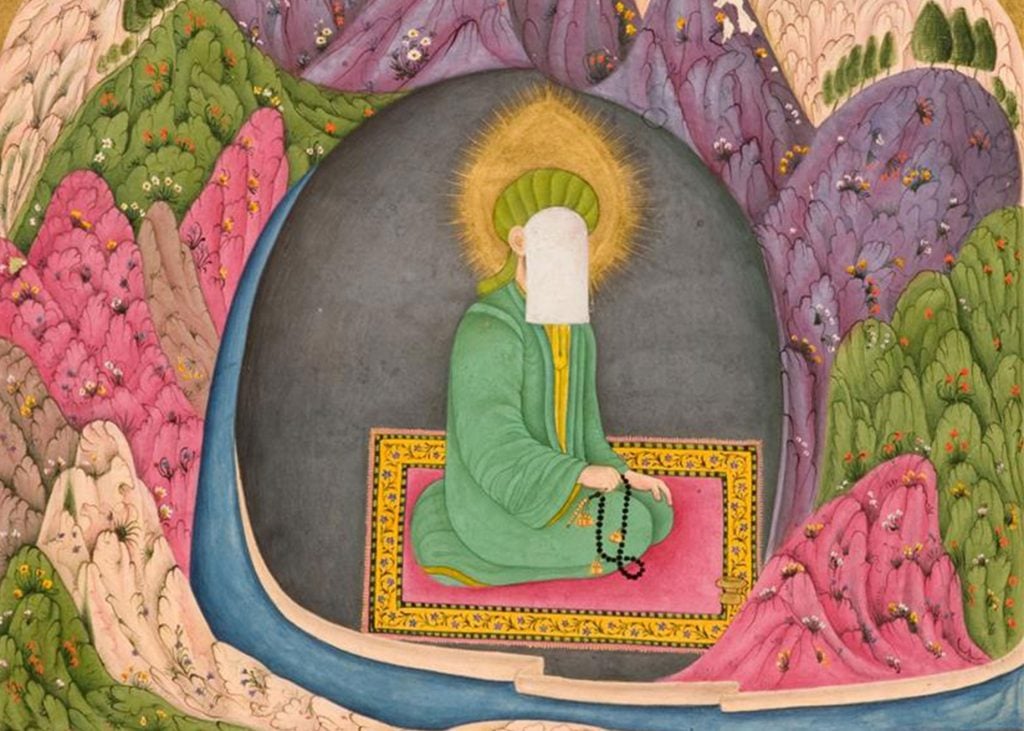

The Prophet Muhammad receiving his first revelation from the archangel Gabriel by Rashīd al-Dīn. Collection of the University of Edinburgh.

The two sides reached a tentative deal on Monday after a 12-hour settlement conference, as reported by the St. Paul Pioneer Press. The terms of the agreement are private, but they have 60 days to finalize the settlement, according to U.S. District Court records.

“The matter has been resolved to the satisfaction of the parties and there will be no further comment,” Mark Berhow, the university’s lawyer, told me in an email. (Prater’s lawyer had not responded to inquiries as of press time.)

An initial ruling from U.S. District Judge Katherine Menendez in September had dismissed most of Prater’s claims, save that of religious discrimination. The judge said it was possible that Hamline had ended Prater’s teaching contract “because she was not Muslim or did not conform to the religious beliefs held by some that viewing images of the Prophet Muhammad is forbidden.”

The dispute’s origins date to an online lecture Prater gave on October 6, 2022. She had informed students ahead of time that they would be studying artworks of Muhammad, both in the syllabus and with a two-minute trigger warning during the class.

The artworks in question were a 16th-century Mustafa ibn Vali work of Muhammad with his face covered by a veil, and an illustration from Compendium of Chronicles, a 14th-century manuscript by Rashīd al-Dīn, of the prophet and the archangel Gabriel.

When one of the students, who was also president of the university’s Muslim Student Association, complained to the administration that the lesson had been idolatrous, it kicked off a firestorm of controversy.

First was the university-wide email from the dean of students apologizing for the “undeniably inconsiderate, disrespectful, and Islamophobic” lesson. Sensitivity to Muslim students “should have superseded academic freedom,” said another email, cosigned by university president, Fayneese S. Miller.

Then came a flurry of articles in the university’s student paper, the Oracle.

There was a news report in which it was revealed that the university had decided to cut Prater lose, and an opinion piece from another professor explaining why the historical artwork wasn’t Islamophobic. The paper’s editorial board removed the latter article after just two days, saying “our publication will not participate in conversations where a person must defend their lived experience and trauma as topics of discussion or debate.”

The maelstrom entered the wider news cycle when Gruber decried Prater’s termination in a December 22 article for New Lines Magazine. She started a Change.org petition calling for the professor’s reinstatement. It received almost 20,000 signatures.

Fayneese Miller retired as president of Minnesota’s Hamline University following the controversy surrounding a professor who lost her job after showing devotional images of the prophet Muhammad in art history class. Photo courtesy of Hamline University, St. Paul, Minnesota.

The academy community and free speech organizations such as PEN America, the Academic Freedom Alliance, and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) came to Prater’s defense, accusing the university of censorship and violating academic freedom. Even the Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC) issued a statement calling for Hamline to reinstate Prater.

By January, Prater had filed a lawsuit accusing the school of religious discrimination, emotional distress, retaliation, and defamation. It argued that the Muslim student had attempted to impose her religious beliefs on the rest of the class by insisting that Prater should not have been allowed to present Muhammad artworks in class.

The university president announced her retirement in April 2023, following calls for her resignation from faculty. (Miller has since been succeeded by Kathleen Murray.) In her exiting remarks, she insisted that Hamline had not committed violations of academic freedom.

The following month, the American Association of University Professors issued a report following an extensive investigation and reached the opposite conclusion. It found that displaying the Muhammad artworks “was not only justifiable and appropriate on both scholarly and pedagogical grounds; it was also protected by academic freedom.”

Depictions of Muhammad remain a thorny issue. Last April, New York’s Asia Society and Museum initially blurred out a pair of artworks featuring the prophet in the online tour of “Comparative Hell: Arts of Asian Underworlds.” The museum changed tacks following accusations of censorship.