Art World

Hank Willis Thomas on His New Work, Charlottesville, and Modernism’s Debt to African Art

We spoke to the artist about his upcoming first UK solo exhibition, identity politics, and America's painful steps towards progress.

We spoke to the artist about his upcoming first UK solo exhibition, identity politics, and America's painful steps towards progress.

Naomi Rea

New York-based, conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas is deeply invested in the idea of representation and, particularly, self-representation. His work urges us to see beyond socially constructed categories of identity, and reminds us that binaries such as black and white or male and female don’t have to define us or the way we relate to one another.

Several of his artistic series have explored the influence power structures (such as advertising agencies and governing bodies) exert over our understanding of the world, and in his work he has used the language of visual culture to speak back to the corporate commodification of various identities.

These questions about identity come to the fore in his latest show, “The Beautiful Game,” which will be his first solo exhibition in the UK. Opening to the public October 5, to coincide with the beginning of London’s Frieze Art Fair week, Thomas will showcase new sculptures and intricate mixed media quilts at Ben Brown Fine Arts in London.

As hinted in the title of the show, “The Beautiful Game” interrogates the sports world on a few recurring motifs of Thomas’s practice: sports’ symbiotic relationship with globalization and nationalism, and the historic and contemporary commodification of a homogeneous black male identity.

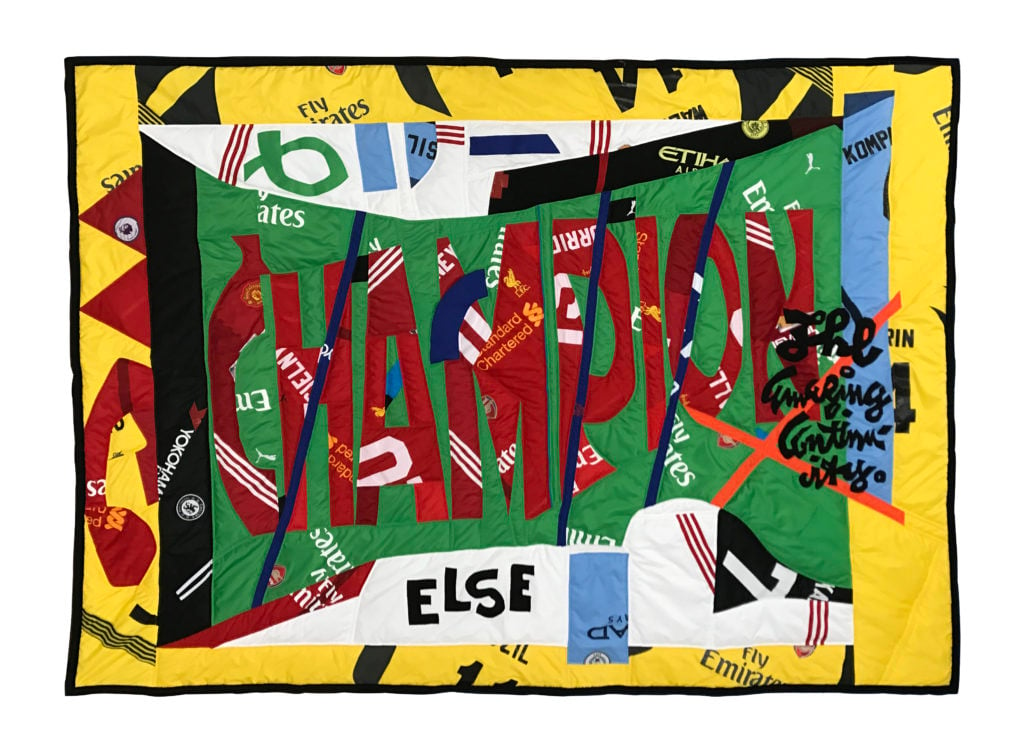

Inspired by various quilting traditions in the US and English militaries, as well as the African-American South, Thomas has fashioned his own quilts out of soccer jerseys (and not the cheap ones, either!) to reproduce works of art by Matisse and Picasso, as well as Asafo military company flags made by the Fante people in Ghana. He will also debut new sculptures, some of which gesture towards Brâncuși.

Recently, we spoke to artist about his new work, his interest in sports, and the catastrophic events that happened in Charlottesville this summer.

Hank Willis Thomas, The Sword Swallower, (2017). Photo: ©Hank Willis Thomas, 2017. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, London.

Let’s start by talking about your upcoming show at Ben Brown, and how it fits within your body of work. Why has your practice been so invested in the sports world, and why have you chosen soccer jerseys as the material for your new quilts?

A lot of masculinity is shaped by perceptions of physical prowess. When I was becoming a man, I realized that although I liked to play sports and I liked to compete, I’m not particularly exceptional when it comes to physical prowess. People are elevated to superhero status just because of their capacity to control a ball with their hands or feet! I think there’s an overemphasis on the value of physical prowess in our society, when it comes to evaluating one’s humanity and virtue.

When I’m talking about black bodies and sports, I’m trying to address that, historically, for many people of African descent, one of the few ways to overcome the negative impact of colonialism and slavery was to show through physical prowess that they could outmatch the Europeans. And if they were able to do that, like we saw with Jack Johnson, Jesse Owens, and Muhammad Ali, among others, that’s when they were able to become, “free” and make more space for others to become freer. Of course you now find they’ve become pretty commodified for the same thing that they were once told that they couldn’t do.

I am also really fascinated with globalization and how sports has been an accelerator, in some ways, of global commerce and cultural hegemony. As the world has become less militarized, sports has become a proxy for that. The World Cup, and the Olympics are proxy wars, in a sense, about nationalism.

You can actually see globalization and the intersection of commerce on the front and backs of soccer jerseys: on the back the players’ names are increasingly global, but then you see international companies like Etihad, Chevy, and Standard Chartered Bank on the front. So the quilts being made from this material is also a reference to the ongoing competition for global dominance in a much more complicated and sometimes hidden way.

Can we tease out some of the other aspects in your quilts: the motifs from Asafo flags, and modernist paintings such as Matisse’s The Sword Swallower (1947) and Stuart Davis’s “Champion” series?

When I first encountered the Asafo flags, I really couldn’t quite understand how they came to be, because of the clear reference to British heraldry in what I’ve come to understand as African and East African mythology and narrative in visual storytelling. As I start to learn and am still learning, the more I realize the marriage is a tale as old as time: somebody said that mythology and storytelling are what brings us power. What brings nations power, what brings cultures power, are the stories that we tell about ourselves and that are told about other people. So I believe that whoever is holding the frame gets to tell the story, and create the reality because history is, as it says in the word: his-story, typically a man’s singular perspective on the past, and so what I love about the Asafo quilts and English heraldry is the way that mythology is kind of made physical and paraded with the flags and the coats of armor.

These quilts are really also referencing, specifically for this show, Stuart Davis and Matisse paintings. I’m very much looking at Matisse and Stuart Davis as both European and American painters who were seen as very early and influential figures in abstract and modern art. Both were interested in popular culture, but also became really interested in abstraction around the time Europe and the United States started to encounter African art in a kind of commodifiable, collectible, way. And, as we know through Picasso and many more, this idea of primitivism is basically the foundation of modern art, and I’m really curious about that. What I am exploring is the maybe “primitive” roots of modern society, and modern art.

I don’t really believe in primitivism, obviously, but I do find it curious. The way that Duchamp, and Picasso, and Matisse, and Gaugin started painting dramatically differently and were praised for their innovations, which were in some cases clearly stolen from unnamed and probably un-compensated artists from the colonies of England and France and Holland. African art IS modern art, it just wasn’t named as such. You could make an argument that modern art is an extension of African Art, and so the way in which a lot of times African artists are put into a category that’s regional, and not contextualised as maybe the foundation of contemporary thought.

Hank Willis Thomas Visa, (2017). Mixed media including sport jerseys. Photo: ©Hank Willis Thomas, 2017. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, London.

What about the sculptures in the show: Your totem currently on view in Frieze Sculpture Park riffs Constantin Brâncuși’s iconic Endless Column, will there be more like that?

There will be two different kinds of sculptures: two more totems, a different variation of that soccer totem in Regent’s Park, and also a rugby totem.

Brancusi’s Endless Column is also a clear reference to African art, and in the United States obviously there’s a lot of Native American art where the totem functions. There’s this idea of reaching towards infinity that happens in the repetition of the form but also the form that begins to have meaning because of the material that I’m using to make the column, and the repetition and the movement that’s implied.

And then there will be two of my sculptures that are based off of photographs. I look at these sculptures as if I could 3D-print a photograph and crop it in a specific place to talk about specific things, so I attempted to recreate Diego Maradona’s “Hand of God,” the decisive moment in the Argentina versus England game in 1982, and then a bicycle kick inspired by Pélé.

Hank WIllis Thomas, Hand of God (2017). Photo: ©Hank Willis Thomas, 2017. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, London.

Many contemporary artists have come under fire in recent years for producing “easy” work that is reactive to the contemporary political environment rather than actively seeking change. In the run up to the presidential election you co-founded the first artist-run political action committee and campaigned for democracy through your Truth Booth project. Do you strive for your work to be politically active?

Well, what does acting look like? I believe that Daniel Buren said that every act is political, which means that all art is political. So it doesn’t have to look like art as we know it to be art, and it doesn’t have to look or sound political to be political. I think we should be very wary of people demanding that others speak in our language. You can encourage people, of course, to use their voice, to speak out, but there is progress to be made on many levels and on many fronts, or as our president would say “many sides.” So no one knows what’s most effective. But I do think it’s important to be visionary instead of being reactionary. The challenge I have and I think many people have in this moment is that we thought we knew what mass destruction was before, but now there’s more of an extraordinary mass destruction…. Who can see past the headlines? How can one be visionary when you are literally overwhelmed with the fear of annihilation? The American presidency has been exposed for all of its flaws, the mask has been ripped off and everyone is staring at all the open wounds and the scars and no one is actually looking at how to heal it because they’re still in shock.

Speaking of shock, what was your reaction to the events that transpired in Charlottesville this summer?

The events in Charlottesville are shocking and surprising and horrible.They also, to me, actually look like the painful steps towards progress. Because of the actions of the white supremacists, there’s been a expedition of the process that was already in motion to remove and recontextualize confederate statues, so in a sense they actually did the opposite of what they wanted to do. By protesting the way they did they actually brought a greater scrutiny to what those symbols actually represent to them, much less the rest of us in society. What I think is incredibly frightening and scary is that something’s bubbling and we don’t know when it’s going to pop, and what it’s going to look like. But at the same time, if we look at the painful progress we’ve made over the past 50 years, the fact that, in this case, the white supremacists are the fringe group, is good. So there’s a real shifting of positions, and a weakening of an already discredited and weakened agenda and perspective.

Hank Willis Thomas, Perseverance (2017). Photo: ©Hank Willis Thomas, 2017, courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, London.

This will be your first solo show in UK. Have you considered how so-called “racial” relations differ here, and how that might affect reception of your work?

I struggle because I don’t really believe in race, and a part of the reason I don’t believe in race is because race is not a uniform. Who gets to be white and who gets to be black changes from country to country, and time to time. So it’s really difficult to talk about “race relations.”

I think that race was created and founded primarily out of the experiment of slavery, turning people into human cargo, and many of the black British people are the descendants of slaves but there are also obviously many people who are immigrants, and the children of immigrants from former colonies and other countries that weren’t colonies of England, so it’s a much more complicated cultural history. In the United States we’re having more and more immigrants from the Caribbean and Africa, but then the notion of blackness that is kind of sold to us is still very much rooted in ideas that were generated during the time of slavery.

I encountered similar issues in another of my series, “Unbranded: A Century of White Women.” To me, it’s less about race than it is about the ways in which people are put into groups and how they are judged and valued upon whatever group they are presumed to be part of. We look at history, for example, and find there were some suffragettes who were abolitionists and some who were not. And there were male African black human rights activists who weren’t necessarily suffragists either, and you recognize how people, even if they have the same struggles, find it difficult to align themselves. We all have that capacity to be both for women’s rights and a misogynist. I don’t know if that’s going to go away but the best we can do is make ourselves and others aware of it, start to question the validity of a racial purity, or a gender purity, so that we can change our own behaviour and our own relationship to what these things are.

There’s no “pure” race, and there’s no “pure” culture. People have been moving around the world and having sex and exchanging ideas for thousands and thousands, of years. At what point were they ever fixed for even more than a few moments, much less centuries?

Portrait of Hank Willis Thomas, 2017. Photo: Levi Mandel.

I believe in multi-nodal and intersectional identity. We are all complex. Whatever I choose to tell you I am first, if I say I’m a man first, if I say I’m black first, if I say I’m an American first, if I say I’m an artist first, that affects the way you relate to me. I am all of those things, and sometimes I’m none of those things, depending on the context. And the more that we accept that, the better off we will all be. I think the danger is that we pretend we are one thing, and that one thing should affect the way that other people relate to us and how we relate to them. Those categories were typically made by people who were more powerful, more influential, as a way to keep people in line. People need to find new forms of agency. That’s the progress. I say the road to progress is always under construction. Every time we reach a certain level of freedom and opportunity, we have that much more work to do. What happened, for instance, after the election of Barack Obama, was that a lot of people put their feet up. “Oh! Racism is done! War is over! Let’s give him a Nobel Prize before he gets to be president,” even though that’s just not how life works. You have to keep working.

“Hank Willis Thomas: The Beautiful Game” will run from October 5–November 24, 2017 at Ben Brown Fine Arts in London. Additionally, the Hank Willis Thomas sculpture “Endless Column, 22 Totems,” is on public view in London’s Regent’s Park until October 8, 2017, as part of Frieze Sculpture.