People

‘He Saw the Spaces Between the Margins’: Adrian Piper, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Others Remember the Legendary Curator Okwui Enwezor

Artists whose careers he shaped and curators whose lives he changed discuss Enwezor's legacy.

Artists whose careers he shaped and curators whose lives he changed discuss Enwezor's legacy.

Artnet News

When Okwui Enwezor, one of the world’s most influential curators of contemporary art, died last week after a long battle with cancer, the world lost one of art’s great minds. During his decades-long career, Enwezor organized numerous acclaimed exhibitions, including the 2015 Venice Biennale and documenta 11 in 2002, and served as artistic director at Munich’s Haus der Kunst for seven years (before his tumultuous departure last year). He promoted a global view of art that forever changed the way art history is written.

We reached out to a handful of artists, curators, and others to reflect on his life and legacy. Here are their tributes.

Thomas Hirschhorn, Bataille Monument (2002), documenta 11, Kassel, 2002. Photo: Werner Maschmann.

One cannot overestimate the importance of Okwui’s vision, of his creative impulse, and of his tireless efforts to transform the art world and its institutions to make possible alternative ways to engage with art beyond our standard thought patterns and western narratives. I got to know Okwui in the mid-1990s and he has remained a friend and a key inspiration all these years. I am eternally thankful to him and will never forget his generosity and intellectual brilliance. What an incredible loss for all of us who care about art and poetry and philosophy and want to feel fully alive in a world in which all of these things really matter.

Okwui is and was one of the most gifted curators I’ve ever known. He saw the spaces between the margins and found ways to give voice to those whose genius was often overlooked.

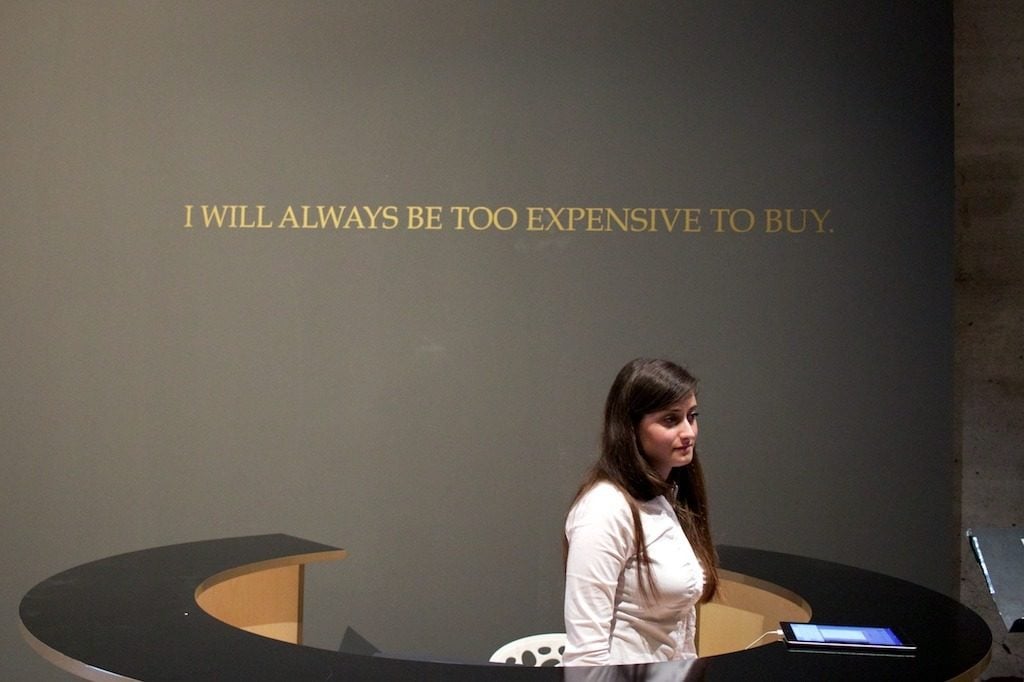

Installation view of Adrian Piper: The Probable Trust Registry: The Rules of the Game #1-3 at the 2015 Venice Biennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor.

None of us can ever know what it was like for him to experience, develop, and exercise his enormous creative and intellectual capacities with full confidence in their power on the one hand, yet to be the unremitting target of envy and malevolence from the mediocre for the exceptional quality of his achievements on the other, because he never discussed it. When directly attacked, he defended himself with dignity and self-control, choosing his words carefully. The rest he bore in silence. I knew more about what he had to bear than I knew him, because the mediocre conscientiously showered poison-tipped arrows of gossip and disparagement in all directions, and because he never complained about them. He just did more great work, making his way calmly among those who flaunted their putative liberality on matters of race by virulently attacking him, because of course if they had been racist, they instead would have patronized him with excessive compliments, right? I prayed that he was as impervious to the poison as he seemed, but didn’t see how that was possible because there was so much of it.

I experienced him in person as a private, courtly, generous and brilliant colleague who beamed when I informed him that we had our Igbo heritage in common, and smiled whenever I reminded him about the traditional virtues of the Igbo warrior. At the dance party after the opening of documenta 11, I saw that his modest demeanor concealed great physical grace and stamina; and that he was a proud, upright man who felt honored, rather than aggrandized, by the intrinsic worth of what he had achieved there, namely that all of us, who would not have been there were it not for him, in fact were there, to honor him. He honored me, in turn, by accepting and welcoming me for who I was. I watched and cheered and prayed for him from the sidelines as he fought his way through and beyond each one of the traps, snares, and set-ups staged by the mediocre, on to one world-class victory after another. He broke through so many barriers of exclusion in his variegated professional activities that in the end, all that could be left of him in any case was a cloud of dust for the mediocre to choke on. I preserved my image of him as the invincible, Stoic Igbo warrior for as long as I could. But even when that was no longer possible, it was clear that his conquests were permanent and could not be reversed, because we will be there to defend them.

Installation view, “El Anatsui: Triumphant Scale” (2019) at Haus der Kunst. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.

These past weeks have been exhilarating and devastating, as I have grappled with my dear friend and colleague Okwui’s illness and passing, while simultaneously opening my solo exhibition at Haus der Kunst. The exhibition, which he co-curated, is the culmination of a decades-long relationship. Okwui and I first met at the beginning of our international careers in the ’90s. He included an article about me, fittingly written by Chika Okeke-Agulu in the first edition of NKA, the journal he founded [with Okeke-Agulu and Salah M. Hassan] which would go on to become a defining resource for African and diasporic art.

I am humbled that even during Okwui’s last days he was determined to engage with and showcase my work. He remained the fiercely passionate curator he always was throughout the entire process of putting together this monumental exhibition, meticulously crafting the checklist and issuing confident directives during installation, even when he couldn’t physically be at the museum. His voice and presence imbues every aspect of the show. Even though he couldn’t join us at the opening, I think he was happy to have had so many visit him when they came to Munich.

When I won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale that Okwui organized, I knew he was giving me as much of a challenge as an honor, a challenge to keep pushing into new territory, to never be complacent, a trait I also admired in him. As I continue to make new work, I will keep that challenge, that support, that friendship, very close.

It’s a devastating loss of a friend, of someone who completely changed the art world. We met in 1996 in London, when Okwui was preparing the second Johannesburg Biennial. He brought together a whole group of curators for this seminal exhibition and he asked me to contribute a text about migratory museums to the catalogue. Migration was a key topic of Okwui’s.

This biennial of his was a game-changing one. It was a major statement towards a more polyphonic, polycentric art world, and it completely changed this idea of what a large-scale exhibition can be. I think it was also a blueprint for many of the other larger shows of Okwui’s that were to come later; documenta being the most famous one, and most recently the extraordinary postwar exhibition at the Haus der Kunst. These large-scale exhibitions he made were bridge-building endeavors, of multiplying and bringing worlds together, rather than creating the homogenizing or standardizing synthesis that museums do sometimes. They were basically performative, experimental spaces—like laboratories.

Visitors are pictured walking along the outside of the international pavilion at the Corderie (rope makers building) on the first public day of the Venice Biennale in May 2015. (Photo: Romano Cagnoni/Getty Images)

These large-scale exhibitions, this German notion of the Grossansstellung, was his medium—but only one of his mediums, because he had so many dimensions. He was not only a curator, he was also a critic, a writer, a poet, and an educator—it’s almost like superstring theory. He was also a publisher, editor, and co-founder of the seminal NKA magazine, which from 1994 onwards addressed the fact that Africa and Diaspora Arts were neglected and which was in a way a protest against forgetting. As Eric Hobsbawm once told me, memory is key for the 21st century as maybe amnesia is at the core of the digital age.

There are entire libraries that should be coming out about Okwui. He leaves behind an immense legacy that will become so much more important in the years to come. Thank you, Okwui, we miss you.

Hiwa K., The Bell at the Venice Biennale, 2015. Courtesy of the Venice Biennale.

Europeans, Westerners,

Who is going to interpret your dreams from now on?

In the Old Testament, Joseph, an outsider, unlike Egyptian dream exegetes, was the only one who was capable of interpreting Pharaoh’s dreams. Though he came from elsewhere, he could read them clearly.

In our times, at the very moment of urgencies that humanity is facing, which include global climate catastrophes, rise of populism and racism, a return to neo-fascism, deepening class divisions and gender inequalities, in such times in which we are very vulnerable, Okwui Enwezor has left us and made us even more vulnerable.

He was the echoic voice, resonating many yet unheard voices from all the non-Western parts of the world. The world lost one of its greatest poets, one of its most vibrant dream interpreters, whilst the West is searching for an image that is identical to itself again.

I first met Okwui in the early fall of 2001, when he was finalizing plans for both “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994″ and for documenta 11. He readily offered the ideas of the shows in ways that I would later recognize as his “seminarial” oratory, a style that found its way into his exhibitions, essays, and public lectures. “Platform” is but one word that I have never used the same way since I heard him explain its relevance to art making. To see Okwui’s exhibitions was to be brought into the conclave of his thinking about the ways that aesthetics and concepts (be they political or material) merge in art objects. Okwui changed the way(s) that curators put together exhibitions, so much so that critics and art historians had to expand to be able to comprehend what they were seeing or, more often than not, what they had previously overlooked.

Installation view of “Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965” at the Haus der Kunst. Image courtesy Haus der Kunst.

Okwui’s passing is a huge loss to those of us who could call him a friend but also a devastating loss to the art community as a whole. His boundless energy, introspection, and intellect made him one of the best curators and museum directors I have ever met. His long battle with this terrible disease was handled by him with such dignity it was humbling to observe and he will forever be a force of nature. The time I spent with him was profoundly special and endlessly inspiring.

We knew it was coming but the finality of his passing makes it even more devastating. Okwui was this enormously prophetic figure, wise beyond his years, whose insights—vision, if you will—literally shaped the universe many of us now inhabit. He was like an enormous tree in the glare, whose shadow provided refuge, hospitality, generosity, and love for so many.