Museums & Institutions

‘The First Time I Saw the Archives I Gasped’: How the American Folk Art Museum Acquired the Vast Holdings of a Shuttered Arts Charity

The Healing Arts Initiative declared bankruptcy after an employee stole $750,000.

The Healing Arts Initiative declared bankruptcy after an employee stole $750,000.

Sarah Cascone

New York’s American Folk Art Museum has acquired the archives of the Healing Arts Initiative, a long-running art charity that served the city’s underserved communities, including the disabled, the institutionalized, and at-risk youth, until it shuttered amid scandal in 2016.

“It’s probably one of the most important acquisitions of an archive in our history, aside from our Henry Darger collection,” Valérie Rousseau, the museum’s senior curator, told Artnet News.

“My reaction the first time I saw the archives was that I gasped,” Regina Carra, the museum’s archivist, added. “There are about 7,000 works by 200 artists. There is so much talent represented—each artist has their own point of view, and that clearly comes across in the collection.”

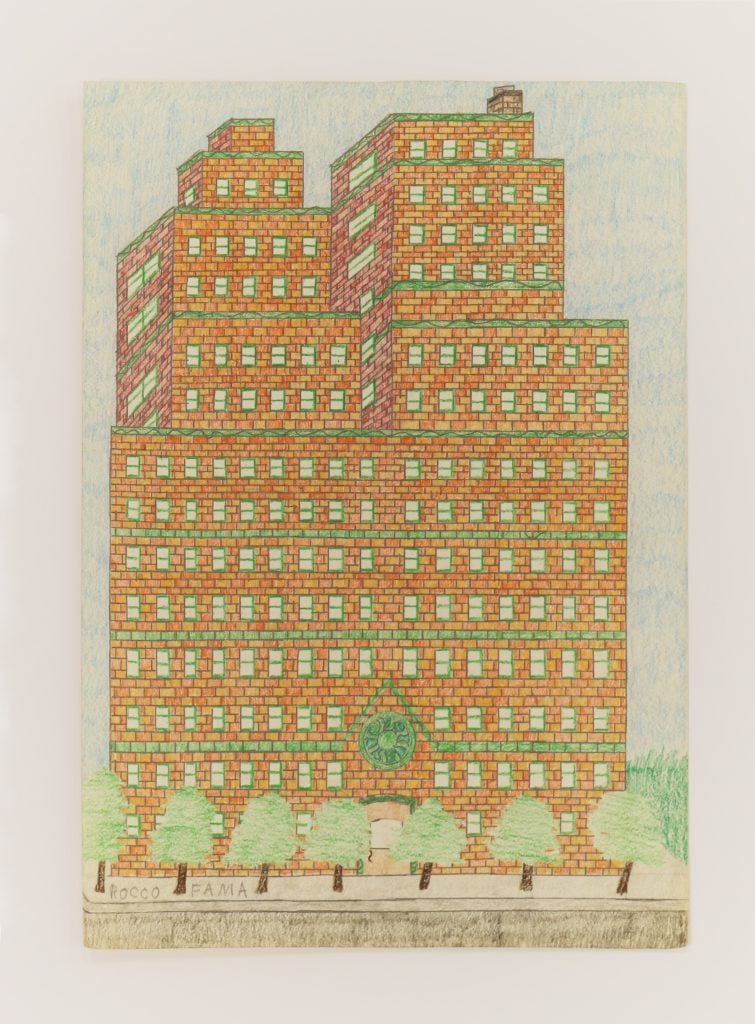

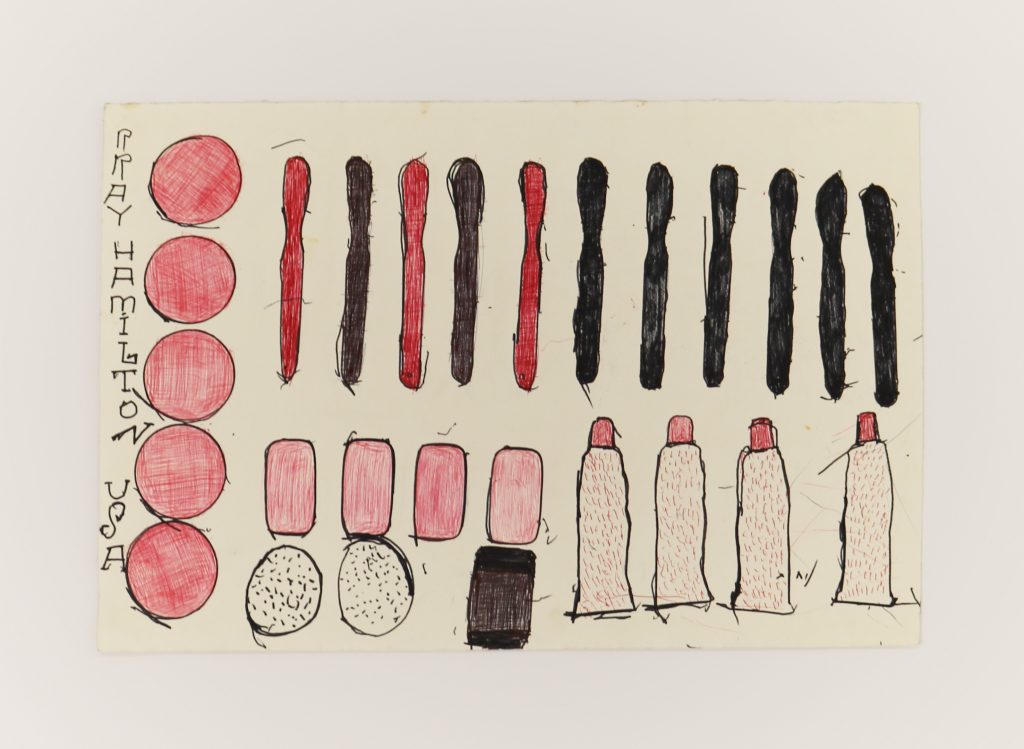

Founded in 1969, Healing Arts Initiative spent nearly five decades hosting artist-run workshops, fostering the artistry of thousands of New Yorkers in need—its annual client base was some 350,000 people. The archives’ paintings, drawings, and collages include work by some of the very first workshop participants, including Lady Shalimar Montague, Ray Hamilton, Irene Phillips, and Rocco Fama.

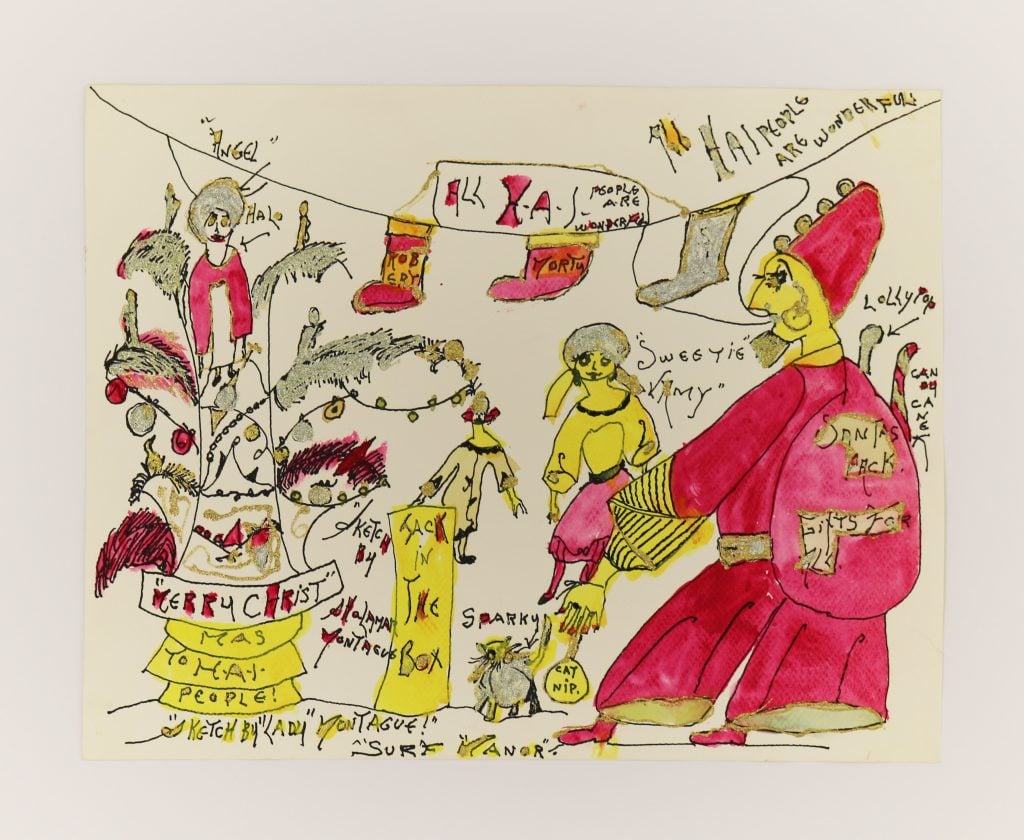

Lady Shalimar Montague, Untitled. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

The Healing Arts Initiative declared bankruptcy after its payroll manager, Kim Williams, embezzled more than $750,000 and then conspired with a hitman on a nearly fatal attack on its executive director, D. Alexandra Dyer, who had been poised to exposure the financial wrongdoings.

Dyer was hired in 2015 to sort out the organization’s books after its debt had mushroomed from $100,000 to $2.2 million in just three years, even as her predecessor reduced staff from 28 to 14 employees, and traded its Soho offices for cheaper digs in Queens.

When Williams refused to provide Dyer access to the accounting system, Dyer hired a new chief financial officer to help investigate the financial situation. That’s when Williams stopped showing up to work and, according to her credit card records, purchased drain cleaner from a supermarket.

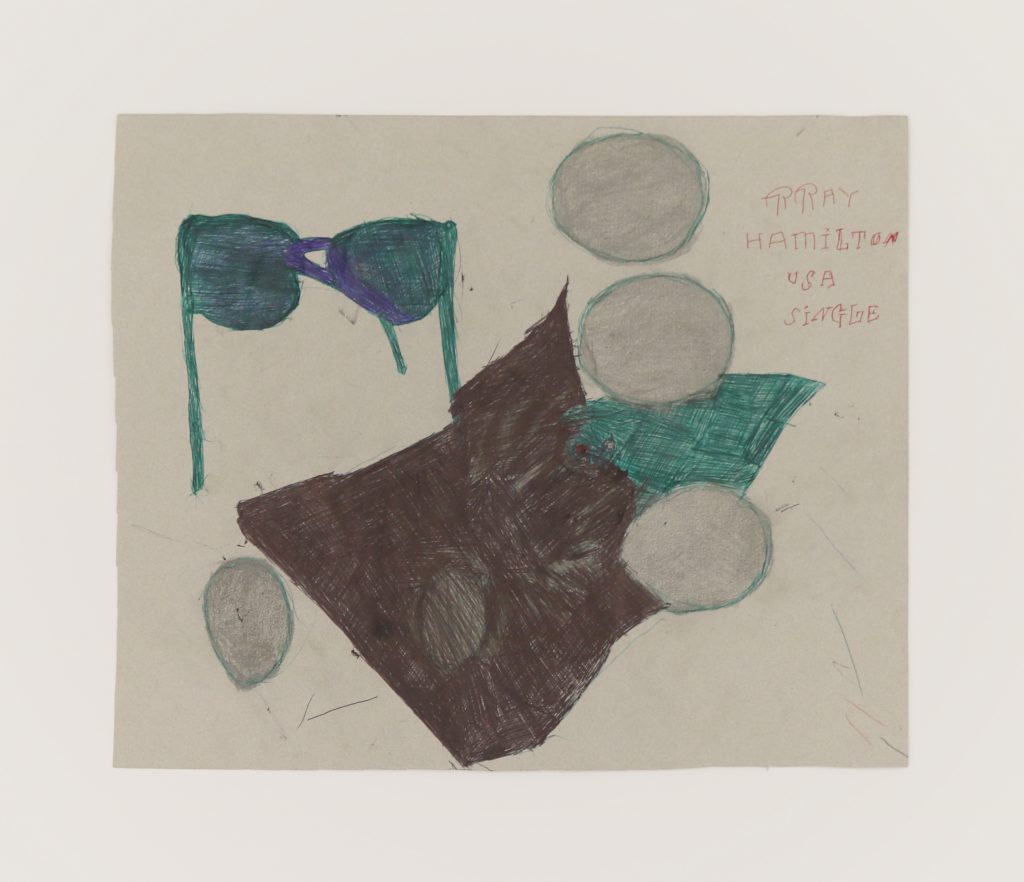

Ray Hamilton, Untitled. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

On August 19, 2015, Williams’s hired assailant, Jerry Mohammed, attacked Dyer in the Healing Arts parking lot, throwing lye in her face.

After multiple surgeries, Dyer remains disfigured, and in 2019, a judge sentenced Williams and Mohammed each to 17 years in prison.

“There was a real fear when HAI closed that this collection would get lost or thrown in the trash,” Carra said.”

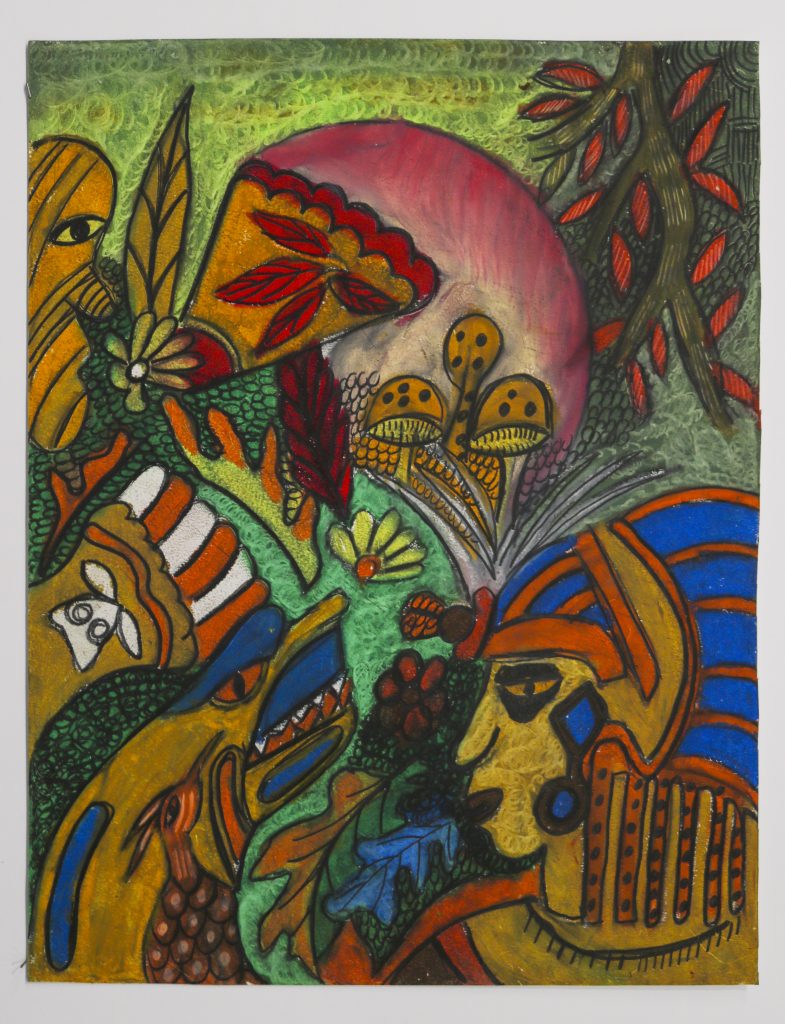

Julius Caesar Bustamante, Untitled. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

Fortunately, New York’s White Columns took temporary custody of the archives in 2017, safeguarding the collection and helping arrange for its permanent home at the Folk Art Museum. (Artists also had the chance to collect their works; the remaining archive remained unclaimed.)

And the work of Healing Arts also lives on at YAI Arts, a New York health and human services nonprofit that purchased the organization’s programming assets in 2017 with the promise of resuming its work with the community. Today, the YAI Arts studio is run by former Healing Arts Initiative gallery director Quimetta Perle, offering workshops to artists with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

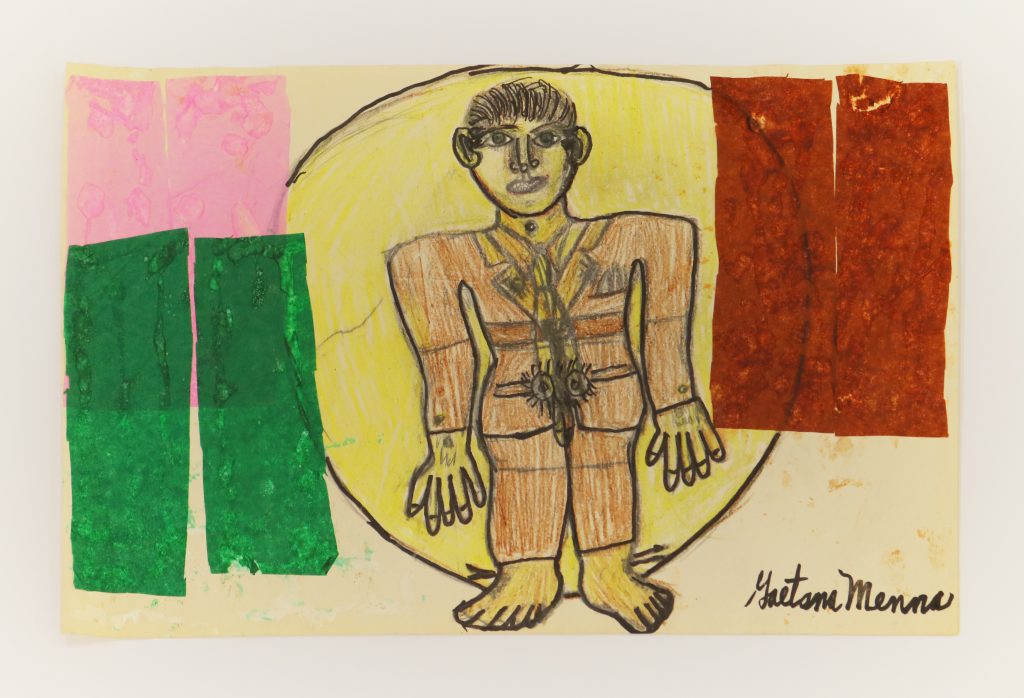

Gaeton Menna, Untitled. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

In safeguarding the Healing Arts’s archive, the museum hopes to put together an oral history of the organization and the artists it served.

“On reflecting about what happened at HAI, I think the story of what went on in those workshops is something that’s gotten a bit lost in the narrative about the organization,” Carra said. “What happened in the workshops? What was it like to participate in them? And what does it mean when an organization like that goes away? Those are questions we would like to explore more as we preserve the archive.”

Rocco Fama, Untitled. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

The museum is also looking ahead to different ways of exhibiting the archive. “There are a couple of exhibitions in the making for the coming two, three, four years about the intersection of psychiatric history, the avant-garde, and different methods of art therapy as they have been explored worldwide,” Rousseau said.

She expects that works from Healing Arts Initiative may find their way into a show about the legacy of François Tosquelles, a Spanish physician who is considered one of the founders of institutional psychotherapy, set to open in June 2023.

Ray Hamilton, Untitled. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

But more importantly, the collection is an extension of the museum’s mission of advocacy and preservation in the field of self-taught art, particularly works created by underrepresented artists, including marginalized people and those with mental illness.

“The HAI collection,” Carra said, “can help us tell the story of the role of these workshops in fostering and nurturing and providing a platform for artists with disability and mental illness—artists who normally don’t have a venue.”